Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

It’s one thing to make nuns funny. It’s another to have a nun cheerily explain the difference between mortal and venial sin, unveil her list of who’s slated for Hell (Zsa Zsa Gabor, Mick Jagger), brandish a gun and shoot two people dead (“I think Christ will allow me this little dispensation from the letter of the law, but I’ll go to confession later today, just to be sure”), and take a bow. But that, roughly, is the plot of Christopher Durang’s short, nutty, blasphemous play “Sister Mary Ignatius Explains It All for You,” which materialized Off Off Broadway in 1979 and became his breakout hit. The Catholic League was not amused.

Durang’s plays—madcap, savage, disturbed—mix absurdism and melancholy, refracting the funny terror of existence. As a lapsed Catholic who was educated by Benedictine monks, he knew that life is full of platitudes tested by the cruel, crazed world. There was real damage in his work, which melded genre parodies (Beckett, sitcoms, Busby Berkeley) with a kooky stream-of-consciousness logic that lifted his characters aloft like helium. “[P]art of the randomness of things is that there is no one to blame,” one of Sister Mary’s traumatized former students says. “But basically I think everything is your fault, Sister.”

For the young and stagestruck, Durang was a gateway drug to dark comedy, and often to theatre itself. After he died, this month, at the age of seventy-five, my social-media feeds brimmed with tributes, from people who had acted in “The Actor’s Nightmare” in high school or directed “The Marriage of Bette and Boo” in college or done a “Sister Mary Ignatius” monologue in Speech and Debate. (The Catholic League is still not amused.) Because his plays had one foot in “Saturday Night Live” and another in Ionesco, he was accessible to young people who loved getting laughs, while offering something weirder and harder-edged than they might have encountered elsewhere. I was one of those people. The first time I saw his work, I was fourteen, and my older cousin was directing his play “Beyond Therapy,” a farce about shrinks, at Wesleyan. Not long after, my drama teacher assigned me a monologue from “For Whom the Southern Belle Tolls,” Durang’s satire of “The Glass Menagerie.” I hadn’t read “The Glass Menagerie,” but the speech—a goofy, heartfelt sendup of Tom’s “I didn’t go to the moon” soliloquy—beckoned me into a world of winking theatrical references. Durang became one of my comedy heroes, alongside such stage absurdists as Tom Stoppard and John Guare.

My senior year of high school, in 1999, I directed my friends in Durang’s play “Baby with the Bathwater,” in which two parents, Helen and John, cooing over a bassinet, desperately try not to fuck up their newborn child—and fail utterly. Helen chides John for calling the baby “Daddy’s little baked potato,” lest the baby confuse itself with food. John dulls himself with quaaludes and sleeps with the nanny. In Act II, the child, now a young man named Daisy—his parents took a guess at his gender and guessed wrong—has grown into a dysfunctional, self-destructive mess, too sex-addicted and depressed to finish a college paper. “I didn’t ask to be brought into the world,” he rants to a psychiatrist. “If they didn’t know how to raise a child, they should have gotten a dog; or a kitten—they’re more independent—or a gerbil! But left me unborn.” The gerbil is funny; the pain is real.

That same year, I went to see Durang’s newest work, “Betty’s Summer Vacation,” at Playwrights Horizons. The play is set at a beach house inhabited by a group of wacky vacationers. A mysterious laugh track hovers around them, as if they’re characters in a sitcom, though the events soon descend into violent mayhem: rape, dismemberment, murder. All of a sudden, three laughing spectators burst through the ceiling, demanding entertainment. “Make us laugh,” they bellow in unison. “Gross us out. Tell us the latest news of Gwyneth Paltrow. Show us naked pictures of Brad Pitt!” After the voices call for a Court TV-style trial, the daffy matron Mrs. Siezmagraff enacts an entire courtroom scene, playing multiple characters, including a nonexistent Irish housekeeper. It was a tour de force for the actress Kristine Nielsen, and one of the funniest things I’ve ever seen on a stage.

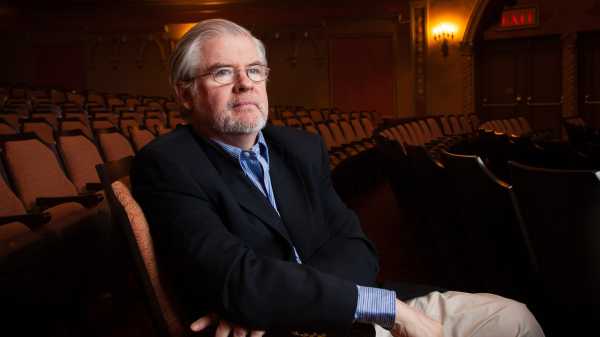

Photograph by Jack Mitchell / Getty

In college, I directed my own production of “Betty’s Summer Vacation,” and somehow got hold of Durang’s e-mail so I could invite him. A few days later, he responded, apologizing that he couldn’t make it. “I hope the play has gone well, and has stimulated but not horrified the audience—which is part of the balancing act needed, I guess,” he wrote. Not knowing the first thing about literary rights, I proudly told him that we’d updated some of the celebrity references, subbing in Justin Timberlake for Tom Cruise. (Note to student directors: don’t do this!) “I have to show my age and say I didn’t know who Justin Timberlake was,” Durang graciously replied. “I hope Gwyneth Paltrow still seemed germane; the sound of her name is amusing to say in unison.” At the time, Durang was the co-chair (with Marsha Norman) of Juilliard’s playwriting program, where he would shepherd generations of talents, including Joshua Harmon (“Bad Jews”) and Branden Jacobs-Jenkins (“Appropriate”). But I was starstruck to have my own little encounter with the master.

More than a decade later, I interviewed Durang for a book I was writing about Meryl Streep. In the mid-seventies, both attended the Yale School of Drama, along with Wendy Wasserstein and Sigourney Weaver, who became one of Durang’s chief muses. Durang had been depressed as an undergrad at Harvard, he told me. He’d had a crisis of faith after he went to worship at a Jesuit house and a young nun declared that, despite the carnage in Vietnam, she still felt hope. (“And I thought to myself, I don’t,” Durang later wrote.) At Yale, Durang fell in with a classmate named Albert Innaurato; both were gay misfits reckoning with their vexed Catholicism by writing viciously funny plays about nuns. At one performance, at a campus art gallery, the duo performed a mashup of fifty plays in five minutes and sang Mass to the tune of “Willkommen,” from “Cabaret.” “It was very crackpot,” Durang told me. “Truthfully, I don’t know where we had the guts and craziness to do that.”

Their collaboration continued with “The Idiots Karamazov,” a spoof of Russian literature, which drew on everything from the Three Stooges to Anaïs Nin. Its narrator was Constance Garnett, the real-life translator of Russian classics, reimagined as a senile, spotlight-stealing hag. For reasons known only to the playwrights, she returns late in the play in Miss Havisham’s bridal veil. Originally played by Innaurato in a floral hat, the role eventually fell to Streep, who—no surprise—stunned the audience with her virtuosic comic performance. “Her aquiline nose was turned into a witch’s beak with a wart on the end, her lazy eyes were glazed with ooze, her lovely voice crackled with savage authority,” Robert Brustein, the all-powerful dean of Yale’s drama school, wrote in his memoir “Making Scenes.” “This performance immediately suggested she was a major actress.”

Durang’s Yale classmates helped form the nucleus of his professional world. He met Wasserstein in a writing seminar; “You look so bored, you must be very bright,” he told her after class. Years later, she used the line in her Pulitzer Prize-winning play, “The Heidi Chronicles.” In 1980, he and Weaver teamed up in “Das Lusitania Songspiel,” an ersatz Brecht cabaret that they performed late at night, in a downstairs theatre on West Forty-third Street. His antic, allusive works latched onto genres like vampire bats, but parody was merely his vehicle for howling into the void. “A History of the American Film” riffed on classic Hollywood; “Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike,” a Chekhov parody starring Weaver and Nielsen, gave him a late-career hit. When it débuted Off Broadway, in 2012, The New Yorker’s drama critic John Lahr wrote that “Durang has struck funny again. It’s as if he had fallen asleep over the works of Anton Chekhov and woken up to find that the plots and tropes of the playwright’s iconic lost souls had migrated from the vastness of Russia to the bucolic tidiness of a Bucks County, Pennsylvania, farmhouse.” The next year, it moved to Broadway and won the Tony Award for Best Play.

The last Durang play I saw was in 2016, at a shell-shocked fund-raiser weeks after the election of Donald Trump. The incandescent actress Julie White performed a snippet from a new work that Durang was then calling “Harriet and Her Heroin Children,” about a brazenly misinformed Republican voter who can’t remember how many drug-addicted offspring she has and cites “fake news” to shore up her addled version of reality. The playwright wasn’t present, but I wrote to him the next day about how funny and unsettling the scene was. “I’ve been very depressed since the election,” he wrote back, “and at first couldn’t write anything funny about it . . . but the Harriet character kind of kept talking.” The play was never produced, and perhaps never finished; that same year, Durang received a diagnosis of logopenic primary progressive aphasia, a rare form of dementia that robbed him of language and, ultimately, his life.

Last week, I dug up my old copy of “Baby with the Bathwater,” scrawled with blocking notes from high school. In an appendix, Durang gives instructions on how to root his farcical non sequiturs in genuine emotion. In a late scene, Daisy storms out of his thirtieth-birthday party, leaving his father swatting away imaginary owls and his neglectful, mad mother bereft. “(Looks sadly out, feels alone),” the script indicates; then the mother sighs. “Weird farce with one foot in reality suddenly switching to sadness with both feet in reality—I’ve been discovering, I think, that this is the approach to take with most of my plays,” Durang advises. “Don’t overdo the sad moments, but don’t pass by them.” It’s a good enough stage direction for living. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com