Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

After the Civil War, the German-born Jewish businessman Isidor Straus moved with his family to New York City. Straus was enterprising and handsome, with small round spectacles, an angular nose, and a coarse, peppery beard. He started off as a crockery vender; by the turn of the twentieth century, he had made millions as a co-owner of Macy’s, befriended Grover Cleveland, served a year in Congress, and fallen in love. His wife was Rosalie Ida Blun, with whom he shared a birthday and seven children. On April 10, 1912, Isidor and Ida boarded the Titanic. She would decline a lifeboat, refusing to be separated from her husband. In James Cameron’s 1997 film, they embrace each other in bed, weeping, as the ship sinks. “I like to imagine they were thinking, ‘This is going to be a movie, we need to get our screen time,’ ” their great-great-granddaughter, Mikaela Straus, told me, taking a hit of a blunt on her couch, in Brooklyn. The last of her line of inheritance had been spent long before she was born. She’s bemused by suppositions about the advantages of her family legacy, which in reality boasts a centuries-deep ledger of addiction, estrangement, and untimely death. Only twenty-six, Mikaela, under the moniker King Princess, has begun to establish a musical legacy all her own. Over the past decade, she’s cultivated a reputation for a new kind of defiant, autodidactic pop stardom. Next month, she will release her striking third album, “Girl Violence”—her best yet—which cements her status not only as a virtuosic provocateur but as a generational talent.

When Straus was seventeen, she wrote and produced her first single, a lesbian pop song that would eventually go platinum. It was her first semester at U.S.C.’s Thornton School of Music, and she was showering in her dorm suite when she started to hum a new melody. She ran, naked and dripping wet, out of the bathroom, and frantically asked a roommate for their phone. Into it, she recorded the first few phrases of what would become “1950,” a snappy serenade to a crush that has since accrued over half a billion streams.

Straus had grown up in a recording studio, where she’d developed a shrewd understanding of pop arithmetic. Blending the honeyed soul of old-school crooners with the synthesized beats that dominated the airwaves and dance floors of her adolescence, she introduced audiences to what would become the King Princess sound: sexy, plaintive vocals, thrumming bass lines, and a fusion of digital and analog instrumentation. Shortly after the release of “1950,” in February, 2018, Harry Styles posted the lyrics on Twitter, garnering hundreds of thousands of likes overnight. Straus would go on to perform the song on “The Late Show with Stephen Colbert,” then on “Saturday Night Live.” What made “1950” ’s success unique was its refusal to conform to the expectations of a Billboard-charting ballad; in a swirl of doo-wop snaps and reverb, it told a defiant, elliptical ode to gay history. “I hate it when dudes try to chase me,” Straus sings, in a raspy alto:

But I love it when you try to save me

’Cause I’m just a lady

I love it when we play 1950

So cold that your stare’s bout to kill me

I’m surprised when you kiss me

The chorus toys with the erotics of bygone danger—conflating the perils of mid-century homophobia with a modern lover’s desire to play hard to get. “I was just thinking about how sad it is that we, you know, are horny for our own oppression,” she quipped on a podcast. Straus, who knew she was queer before she could write her name, was a lonely child. Though her parents were largely supportive of her sexuality, others were not: when she walked down the streets of New York holding hands with girlfriends as a young teen-ager, passersby would hurl expletives, slurs, and occasional threats. For company, she turned to literature—Radclyffe Hall’s “The Well of Loneliness,” Rita Mae Brown’s “Rubyfruit Jungle,” Nella Larsen’s “Passing,” Fannie Flagg’s “Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe.” She particularly loved “The Price of Salt,” the only happy ending she encountered, and subsequently read every biography she could find of Patricia Highsmith and her lovers. She wrote the song as a way to reach across time toward them, to find a companion in history.

That spring, the producer Mark Ronson heard Straus’s demos in an A. & R. meeting at Sony. They got dinner—a meeting she’s described wryly as a first date—and, struck by her raunch and then by her technical acumen, he signed her. (One of his favorite songs of hers is called “Pussy Is God.”) After Straus received an advance from Ronson’s imprint at Columbia Records, Zelig, one of the first things she did was pay off some forty thousand dollars in outstanding student loans. Her début EP, “Make My Bed,” opens with a prayer of thanks: “Eighteen years I spent / waiting for this.”

In June, Straus told me how her time at the label ran its course. “We have enough documentaries about Britney Spears to know how it works,” she said, shrugging and packing her lip with Zyn, the nicotine pouches she’s substituted for a vaping addiction. She recalled how she and her mother—whom she jokes is the “D-list Kris Jenner”—had hired a lawyer to exegete every line of the contract for her, “and I still got fucked.” After seven years at Columbia, she left. “In L.A., I had become addicted to my own unhappiness. It reached a point where I was like, ‘I will die if certain things don’t change,’” she told me. “Mark was like a parent to me. He was gracious enough to let me go.” She made her new album, “Girl Violence,” free of oversight or contractual obligation, then scouted for distributors, landing with section1, the tiny partner label of the independent, Brooklyn-based Partisan Records. Their enthusiasm and compassion had surprised her. “I wasn’t used to people not caring about streams or views,” she told me. “Good art is not born out of fear.”

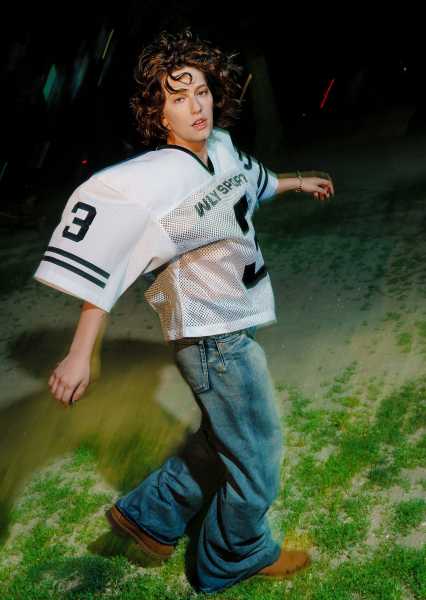

Straus, whose elfin face is framed by a piecey shag, with arched pink lips, a delicate nose, and hazel eyes underscored by creases that make her look a little strung out, was setting up for her semi-regular queer costume party, BAZONGAS, at a warehouse in East Williamsburg. The theme was “Slut Funeral”—a celebration of her new album’s lead single, “RIP KP,” and her own symbolic rebirth—and a handful of employees from Partisan were moving a two-hundred-pound steel casket to the lip of a stage, which had been decorated with more than forty fake candles. Helping with the manual labor in a ribbed white tank top, shredded jeans, and Timberland work boots, she joked to me that she had no security concerns about throwing a party open to the public: “What are these, like, weird, funny lesbians going to do to me?” Her anxieties about the exposure had more to do with her own behavior. “I had decided in my head that I wanted to be of the people, and around people, and available to people, so what if I fucked up?” she told me. “What if I have too many drinks, or get embarrassed or defensive?”

Straus modulates between a kind of studied languor and a firebrand’s stridency. “They’ve tried to media-train me at least eighteen times,” she said, within minutes of our first meeting. She repeatedly glanced at her publicity team as we spoke, even when they were out of earshot. The meta-acknowledgment of her ungovernability can seem strategic—as if it might make a journalist, or a collaborator, put less stock in her brash pronouncements.

Chris Robbins and Brontë Jane, the married founders of section1, first met Straus over Zoom. It was Valentine’s Day, and Straus introduced herself to her prospective bosses by describing the lingerie her girlfriend had brought over. Robbins recalls thinking, “Only one of you exists in the world.” Straus was mouthy, sharp, and knowledgeable, recalling the punky theatrics of Courtney Love and Gwen Stefani, but the pair were most compelled by the paradox of a certain calculated authenticity—she wielded vulgarity with the choreographed poise of a clown. “It’s this idea of Mikaela as a total fucking rock star, but in the most self-aware, almost self-parodying way,” Jane explained.

Straus’s approach to her new album reminded Jane of one of her favorite films, Ingmar Bergman’s “Persona,” in which a young nurse struggles to distinguish herself from her patient. The whole conceit of “King Princess” is arranged around a fun-house effect—seeing iterations of yourself that aren’t exactly you but which you nonetheless identify with. Straus took inspiration from the Surrealist French artist Claude Cahun (also androgynous and pseudonymous), whose uncanny self-portraits troubled the possibility of documenting a “real” self.

“I still don’t know if I’m supposed to call her King Princess or Mikaela,” Hugh Jackman told me. He acted opposite Straus in the forthcoming film “Song Sung Blue”—her feature début—and, in April, invited her to join him onstage at his Radio City residency. They duetted Sonny & Cher’s “I Got You Babe,” and he recalled being taken by the immediacy of her performance. “She had rehearsed with the orchestra, but I felt like she was discovering the song for the first time as she sang it. That kind of confidence can’t be taught.”

When Straus was a teen-ager, musician friends would designate certain sessions in the studio with her as “king princess days,” summoning a punk-diva spirit to the console: Mick Jagger in a bustier. (“I’m literally fifty-fifty,” Straus told me, of her gender. “There’s a huge disconnect between my body and my soul. I think that disconnect is powerful if it’s harnessed, but sometimes you wake up and you’re, like, ‘If I put clothes on this carcass, I’m going to kill myself.’ ”) Her relationship to womanhood, which has been fraught and erratic since a tomboyish childhood on the baseball team, relies on notions of drag and extravagance; if the standard is a caricature, she can’t fail in its execution. For her birthday, in December, she threw a Harry Potter-themed BAZONGAS and dressed in full prosthetics as a busty, camel-toed Voldemort.

But the primary reason for dividing her identity is psychological. “It’s like E.M.D.R.,” she explained, referencing a form of therapy in which a patient alternates between positive and negative memories. “The whole thing is to create a safe place in your mind you can go to when things get overwhelming. King Princess is that for me.”

Mikaela Mullaney Straus was born to Oliver Straus, a recording engineer, and Agnes Mullaney, who worked in fashion; they would separate by the time she turned three. The young Mikaela, responding to the fights whirling around her, began to lash out in turn. She also channelled her emotions into art. When she was six, her mother picked her up from a babysitter who informed her that Mikaela had written a song on GarageBand called “It’s O.K. to Be Wrong.” “Before I used music to impress anyone, I used music to cope with my very big feelings,” she told me. “I needed an outlet.”

Mission Sound, an esteemed Brooklyn recording studio founded by Straus’s father, began in the cellar of the Williamsburg house where she grew up. At first, it was difficult to coax clients across the river—Oliver has described the neighborhood in the early nineties as “Siberia to Manhattan musicians.” Soon, though, he amassed an impressive portfolio of local artists, which now includes such hitmakers as Jack Antonoff, the National, and Shawn Mendes. After buying the two-story fixer-upper for seventy-five thousand dollars, Oliver invested in a Neve 8026 console that had been used by the likes of the Who and the Kinks. To accommodate the upgraded gear, he expanded his business into an old factory, where he still runs it, half a mile away.

When Oliver and Agnes separated, she kept the house, and he moved into a small room next to the new studio. He installed a kitchenette and, in order to share custody of his daughter, built her a loft bed over his floor mattress. From the time that she could walk, Mikaela would sneak across the hall to play with whatever she could—microphones, guitars, keyboards, faders, all manner of expensive equipment that she regarded, to her father’s moderate distress, as toys. Musicians and audio engineers came and went, and Mikaela would sit on the couch behind them, imitating their riffs and vocal exercises. Sometimes a patron, taken by her precocity, would give her a lesson. She can play almost anything. (“I’m sort of a Swiss Army knife, except no woodwinds,” she told me.) When she was five, she finally earned her father’s praise by composing her first song, a clever jingle about her dog Jackie, and he recorded it on the Neve. But after he started a new family with a second wife, their relationship frayed. By the time she finished middle school, she’d taught herself to use the audio software Ableton Live so she could make music without him.

“I think people think my dad was the type of person who could call up the head of a label and be, like, ‘My daughter!’ ” she told me. Instead, the chief privilege of her father’s profession was proximity. Through the studio, she’d met a songwriter who’d introduced her to a manager who’d introduced her to a producer, Mike Malchicoff, who helped her record “1950.” “If I was shit, nothing would’ve happened,” she said. (The bravado she traffics in can feel defensive, but not baseless.)

Meanwhile, her mother’s house offered its own revolving door of mentors. Agnes, who has been sober for thirty-nine years, was a twelve-step sponsor, and the home was always bustling with guests from the program. Growing up, Straus said, “I was obsessed with very flawed people. You have to look at somebody’s character and be, like, ‘This is a good person, even though there’s fucked-up shit here.’ ” Agnes, aware that addiction ran in the family—she had met Oliver when both were in recovery—was terrified that similar dangers might befall her daughter. “For all the incredible patience she had with her sponsees, I got none of that,” Mikaela recalled. “But it was out of fear. And she was right.”

In high school, she was disorganized and distracted. She attended Avenues, a private school in Manhattan, on financial aid and an arts merit scholarship. She smoked cigarettes in the bathroom, cheated on assignments, and rushed home to practice piano. That she was gay and believed she would one day be famous made her a tough hang for most. (“I don’t think I’m really that likable,” she once said, offhand.) But her difficulties in her weakest courses forced her to hone a different asset. She knew she needed to do something to distract her peers and instructors from a paucity of right answers—so she learned to make them laugh.

Across thirteen slinky, dancey, scuzzy tracks, “Girl Violence” chronicles the frivolous, sexy havoc Straus has seen women wreak on one another’s lives. Almost all the associated visuals and concepts were her ideas. The cover art, an out-of-focus closeup of Straus’s face, pays homage to Blur’s self-titled album. The music video for “RIP KP” finds Straus, after a car wreck, in gay Hell: a place where strippers in leopard print strain Martinis through their toes and the bathroom attendant accepts tips below the skirt, placing them in the open maw of a muppet merkin.

The record, which was completed late last year, got its start in the winter of 2022, after her sophomore venture, “Hold On Baby,” saw critical acclaim but only modest commercial returns. She had been working on a collection of new songs, including “Cry Cry Cry,” a bratty diss track with an infectious bridge. The label wasn’t sold. Straus was increasingly miserable in Los Angeles, navigating the breakdown of a four-year relationship and struggling to curtail her substance use. On a visit to New York, she met with two very different Brooklyn producers: Jacob Portrait, a warm but aloof multi-instrumentalist from the psych-rock band Unknown Mortal Orchestra, and Joe Pincus, an affable software geek who had programmed beats for Doechii and SZA. (“I think if you look at the three of us on paper, you’d be, like, how the fuck would this ever work?” Pincus said.)

That summer, she left her label, her lease, and her relationship. It was time to go home. She returned to her mother’s house (and, as she made a point of mentioning when we met, now sleeps in the bed where she was conceived). In September of 2023, she booked a month at her dad’s studio with Portrait and Pincus. Oliver would make them dinner and pop his head in excitedly if he heard Mikaela shredding a guitar solo, but he mostly left them alone. “Having another cook in the kitchen, especially her dad, was not something Mikaela was interested in,” Portrait said. “He’s been in this business a long time. They both have really big opinions.” Eventually, Straus showed her father the finished record. He said that it sounded like Mission Sound. “That’s the highest compliment coming from him—that it sounds like his room,” she told me.

Some of the new album is about her ex, including the swaggery, synth-heavy lament “Alone Again.” On the outro, Straus sings, “I got bigger dreams than being your baby / Honestly, I’m so relieved it’s over.” But “Girl Violence” is not a straightforward breakup album. Instead, it uses her heartbreak as a metaphor for other kinds of fissures and reinventions. On “Origin Story,” a hip-hop-percussive hero’s journey, she sings,

I’ve had to face fire, fight fear

and spend a lot of time in the mirror

I’m cool, I’m weirder

Yeah, I’m hot, I’m deeper

I’m starting to feel myself again

Until now, Straus’s work has flipped between styles like a jukebox. Unlike many popular artists, she was never classically trained or in any other bands, nor was she plucked from obscurity to perform assembly-line creations. More than anything, thanks to her childhood at Mission Sound, she was a mockingbird. Her discography feels like the output of, appropriately, a Zelig, rather than the committed expressions of a singular mind. Across two full-length albums, one EP, and a handful of singles, Straus has offered variations of R. & B., grunge, disco, electro-clash, funk, alternative, and soul. She has collaborated with Fiona Apple and the late Foo Fighters drummer Taylor Hawkins, performed onstage with Julian Casablancas and Florence Welch, and covered Neil Young, Cyndi Lauper, Hole, Soundgarden, and the Velvet Underground (twice). She was raised on Led Zeppelin, Prince, David Bowie, and Jack White; she worships the Beatles’ live sessions. Identifying the latent similarities among her influences and doing away with anything ornamental or aspirational, “Girl Violence” finds its footing in late-nineties electronic rock. (“I feel like my live show has always been a rock show, even when I’m playing pop music,” she said. “Which is just to say that genre is meaningless.”)

It’s her happiest album, sonically and lyrically, with only one ballad: the closer, “Serena,” which is a lullaby to a friend. “Cry Cry Cry,” released last month as the second single, is the standout. Its opening line—“Well, fuck me, I thought we were friends”—recalls the whiny yowls of Blink-182’s Mark Hoppus. It also highlights the greater-than-the-sum-of-its-parts effect of the producing trio’s differences: Pincus, who has been nominated for a Grammy, brought his pop expertise, shoring up the twinkly harmonies and tight ’NSync drums, while Portrait drew on his background in the D.I.Y. scene, complimenting Straus’s pastiche bravura with a rough-edged Wheatus sleaze. Pincus’s textures are contemporary, but the references and use of real instruments by the other two make the finished product feel timeless. Straus, Pincus, and Portrait engineered “Girl Violence” themselves, forgoing the type of celebrity mixers she’d hired in the past. This time, wanting to figure out what “King Princess” actually sounded like, Straus went her own way.

On a punishingly hot Wednesday night in June, Straus hosted a surprise preview show for “Girl Violence” at Market Hotel, an intimate, grimy standing-room venue that rattles when the subway passes. Save for the première of “RIP KP” on “Colbert” the night prior, it was her first time performing before an audience in years, and she was nervous, hiding out beforehand in the green room with her girlfriend. She would play the album all the way through with a mostly new band, in addition to her longtime drummer, Antoine Fadavi, and her bassist, Logan McQuade, who’d been beside her at the first-ever King Princess show, a Halloween party in 2017. (She was Ripley from “Alien”; he was a vague approximation of Jack Black in “School of Rock.”) “I can’t imagine being on stage without him,” she confessed, in a rare fit of sincerity.

Straus shook off her dread as security guards escorted her through the crowd, teen-age girls squealing and clawing at her as she passed. “I missed you, New York,” she yelled under a rosy spotlight, wearing another skintight white tank top, this one bearing the name of her record across the chest. Hundreds of fans roared back. A louche, old-school performer, she channels Robert Plant and Iggy Pop, and elicits similar erotic zeal from her audience. As she sang, even with a guitar strapped to her shoulder, she ran her fingers up and down the mike stand, along her bare stomach, and through her curls, dripping with sweat. The new record is full of horny couplets, which she discharged without flinching. When she paused to slug a cherry-red cocktail, a fan screamed, “I love you!”

The gig, which had sold out in nine minutes, was all-ages. Hours before showtime, dozens of young people, mostly queer women, had begun lining the noisy Bushwick block outside. Two sixteen-year-olds in baby-doll dresses and smears of thick eyeliner had come up from Long Island. “It’s hard to find people like this where I’m from,” one of them told me shyly. Nearby, a woman in her mid-fifties, who had taken the train in from Philadelphia for the set, waited for her wife to bring back drinks from the bar. She emphasized how much it meant to her to be in a majority-gay space. She’d grown up in the Pennsylvania suburbs and had come out, catastrophically, at thirteen; this year alone, more than a dozen anti-L.G.B.T.Q. bills have been proposed in her state. What she loved most about Straus, she said, was that “she’s unapologetically queer.”

Toward the end of the set, Straus introduced a bluesy rendition of “1950” by entreating the crowd to sing along. “If you think about it, this is really where the girl violence started,” she said, taking a seat at the piano. “Crying over some pussy, as it goes.”

Straus appreciates the environment at her shows, where, she told me later, “I’ve seen people get fingered, but I’ve never seen a fight.” She was sitting in the greenroom, curled up on a mottled brown-leather couch. “Sometimes,” she said, resting her head on her knees, “you’ll finish your set and a kid will come up to you and be, like, ‘I got kicked out of my house. I have forty dollars, and I bought this ticket.’ It really fucking changes things when you hear that.” She seemed offended when I asked if it ever felt like too much to bear. “I think part of the job of an artist is to be a listener. It’s not just about talking and playing and performing. It doesn’t take anything away from me—it gives me a reason to do this other than myself.”

A week after Market Hotel, Straus was ready to let me see her home. “I need to smoke a blunt,” she said, leading me through a manicured courtyard with patio furniture and hydrangeas, where she sometimes inflates a kiddie pool for her dog, Raz, a six-year-old border-collie mutt who met us at the door. (The previous owners had named her after her affinity for raspberry White Claw.) Straus knelt down and let Raz kiss her face. “I’ve had her since she was five months old,” Straus told me, massaging the floppy ears with her thumbs.

She led me upstairs so she could change into a pair of athletic shorts. I asked if the room had been her parents’. “Just my mom,” she said quickly. Behind her, the bed was neatly made, and an A.C. unit ruffled the leaves of a plant that hung off her armoire. When Straus got into U.S.C., her mother relocated with her third husband to Hawaii, where she keeps horses. Straus moved into her dorm room with the help of her manager rather than a parent. “She comes to New York a lot, and we talk on the phone every day,” Straus said. “But it is far. She missed the last show, which I know was hard for her.” On her upper arm is a tattoo of a bridle bit under the word “MOM.”

Afterward, Straus rolled her contraband at the kitchen island and lit up, offering me a hit. (I politely declined.) On the walls hung White Stripes, T. Rex, and Yeah Yeah Yeahs posters. In her living room, PlayStation controllers, bundles of sage, a medieval sword, and packs of Zyn were shelved together under a glass coffee table. A nine-foot-tall stand of books—among them, the collected poems of Emily Dickinson, a Lou Reed biography, and “Gimpel the Fool,” by Isaac Bashevis Singer—was topped with a stack of wigs. “There are wigs everywhere, if you want to wear one,” she said, following my gaze. Would it make her more comfortable if I made a fool of myself? She told me that it would.

Scattered among novelty objects, including a wax candle of a woman’s crotch and a signed portrait of RuPaul, were accolades from her career: late-night-show call sheets, an “S.N.L.” plaque, and the framed platinum vinyl for “1950.” For every measure of her efforts, there has to be a punch line to undercut it, or perhaps to make it seem all the more impressive. She kicked back on a sectional, letting Raz splay across her lap, and I asked what she hoped people might take away from “Girl Violence.”

She hit the blunt contemplatively, and then answered. “I hope that it just feels like I’m having fun.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com