Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In “Weegee’s Secrets of Shooting with Photoflash,” a 1953 instruction manual for hobbyists and would-be professionals, the famed photojournalist Arthur Fellig offers this piece of advice: “A news picture is like any other commodity. . . . It can always be sold if it’s good. It is also a perishable commodity . . . so—act fast!” His counsel was based on much personal experience. Fellig was born, in 1899, to Jewish parents in present-day Ukraine. By 1909, the family had immigrated to New York. Fellig began freelancing for the tabloid press in his thirties. He became so well known for the speed and acuity with which he was able to get a “good” picture, that he quickly took on the name Weegee (a homonym for “Ouija,” it supposedly nodded to his uncanny ability to predict when something worth shooting was about to happen). Weegee’s most successful photographs captured events like fires, car crashes, crime scenes, and their aftermath; the value of the pictures relied on their immediacy and sensationalism. And yet, paradoxically, the intended ephemerality of his images—their glinting, flash-lit air, their propitious formal arrangements—is what has granted them a lasting significance, which has grown only more potent in the twenty-first century.

“Murder on the roof,” 1941.

A retrospective of Weegee’s work is currently on view at the International Center of Photography, on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the neighborhood where many of his best-known pictures were taken, nearly a century ago. The show posits that the importance of Weegee’s images lies in his instinctual grasp of what the French Marxist philosopher Guy Debord called “the society of the spectacle,” the titular concept he explored in his 1967 book. In the study, which consists of more than two hundred and twenty theses, Debord argued that, under capitalism, “everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.” For Debord, commodity fetishism “attains its ultimate fulfillment in the spectacle, where the real world is replaced by a selection of images which are projected above it, yet which at the same time succeed in making themselves regarded as the epitome of reality.” Weegee’s pictures of disaster, crime, and urban blight not only grabbed viewers’ attention but highlighted the ways in which passive spectatorship had come to dominate our lives as citizens. “News photography is my meat,” Weegee once said; on another occasion, he noted that murder and fires were his “bread and butter.” The nourishment metaphors he employed are oddly apt: Weegee knew that his images, these all-too-perishable commodities, were feeding both his career and the hungry, yearning masses. His genius as a photographer lay in his ability to reflect and critique what the show’s curator, Clément Chéroux, calls “the reduction of the world to spectacle.”

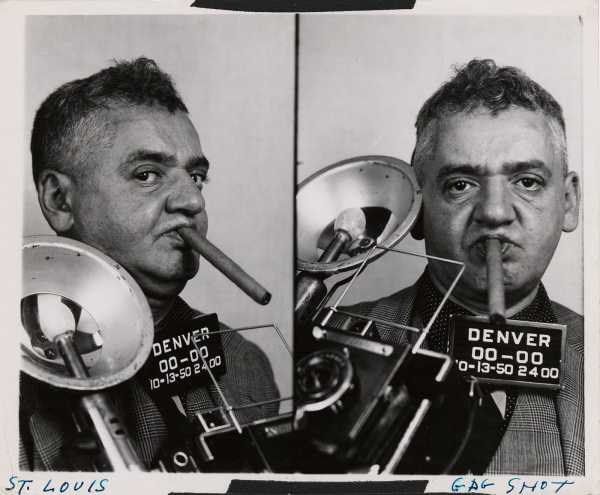

“St. Louis Gag Shot,” 1950.

In Chéroux’s catalogue essay for the exhibition, he argues that this critique often manifests itself in Weegee’s pictures as satire. When I visited the show recently, I could see what he means. There is a sly archness to many of the images, whose backs the photographer often stamped with the extravagant credit “Weegee the Famous.” In a series of self-portraits, for instance, Weegee humorously mythologizes his persona as a hardboiled man of action, always in pursuit of the next attention-grabbing scoop. The work “Weegee Covering the Morning Line-Up at Police Headquarters” (ca. 1939) shows the photographer crouching on the jutting second-story cornice of a brick building, camera and flash at the ready, right above an enormous novelty revolver used to mark a gunsmith’s storefront. With a rakish cigar in his mouth, Weegee seems to be asking: Is this firearm large enough to grab your eye? This sort of implicit address to the work’s spectators, and to their unquenchable thirst for more, also crops up in some of the photographer’s graver pictures. In “Chalk Outline” (ca. 1942), Weegee captures the aftermath of a murder. Although his photographs often document slain bodies arranged limply on the sidewalk, this particular image includes only the barest of markers to indicate where a body once lay. The outline is abstract: rather than the traditional sketch of a person’s contours, there’s a crudely drawn rectangle whose top is simply marked with the word “head,” as if self-consciously resisting the viewer’s desire to gawk at death’s most graphic incarnation. A series of photographs that depict detained criminals covering their faces similarly pushes back against both the photographer’s and the spectators’ desire to rip away the drapery of respectability and look at the bald truth underneath.

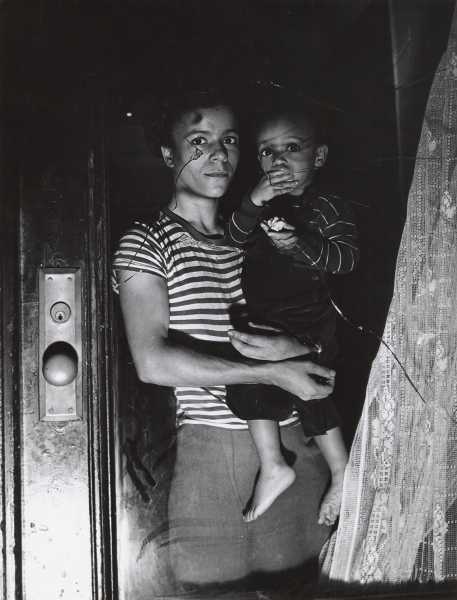

“Mrs. Bernice Lythcott and son looking through window shattered by rock-throwing hoodlums, Harlem, New York,” 1943.

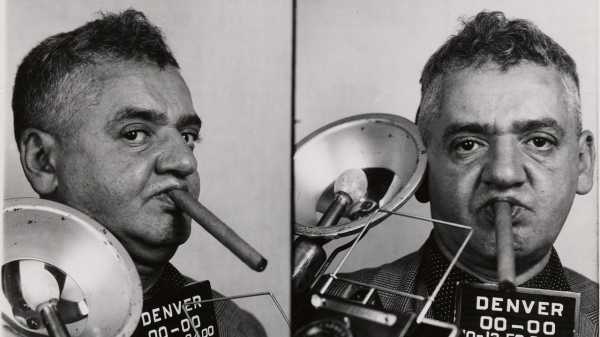

This desire—suggested, obliquely, by the title of Weegee’s first photobook, “Naked City” (1945)—is captured in another strand of the photographer’s work, which the I.C.P. show also includes. Weegee was fascinated not only by the events he witnessed but by their resident gawkers, or, as the title of one chapter in “Naked City” called them, “the curious ones.” In “Murder on the Roof” (1941), we see two detectives ministering to a dead body lying prostrate atop a grimy building, and the row of spectators who have gathered to watch the action from a roof next door. Despite the grim proceedings and grubby environment, the spatial arrangement of the image brings to mind a theatre balcony packed with eager punters ready to consume their money’s worth of entertainment. The mood is more sombre, however, in images that capture the faces of spectators in tighter closeup. In “Their First Murder” (1941), we see a group of urbanites caught in the act of viewing, though apart from the information given to us in the picture’s title we can only imagine the particulars of the event they are privy to. Their expressions run the gamut from laughter to confusion to agony, and there is something shockingly vivid about them, not unlike Munch’s “The Scream,” or the masks of tragedy and comedy. These are people whose subjectivity is defined by their act of spectatorship.

“Lovers at the movies, New York,” (1943).

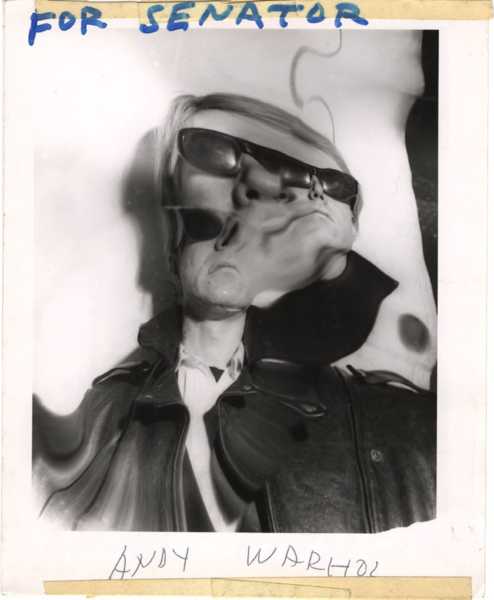

After spending more than a decade shooting in New York, Weegee decided, in 1948, to leave it behind for Hollywood. The geographic break corresponded with a pivot in the photographer’s work. Scholars who lauded the “Naked City”-era Weegee as a modern master have tended to see his Los Angeles era as reduced and ridiculous. (John Szarkowski, the head of MoMA’s photography department between 1962 and 1991, called it “profoundly vulgar work.”) This critical shift was largely due to the radically different approach to photography Weegee took after he exchanged coasts. Turning away from the subject of urban catastrophe, he became interested in celebrity culture, and rather than continuing to apply his documentary approach to this new subject matter, he began using a slew of gimmicky photographic tricks, manipulating his images through mirrors, prisms, plastic sheets, and double exposures, all under the banner of what he called “the elastic lens.” His portraits of celebrities such as Marilyn Monroe, John F. Kennedy, and Elizabeth Taylor appear fun-house-like. Distorted and exaggerated by Weegee’s hand—with grins set in a chilling rictus, or eyes and noses spread wide and pancaked—these idols became monsters.

“For Senator Andy Warhol,” 1965.

The I.C.P. show makes the case that Weegee’s two eras, for all their differences, are part of one coherent corpus, united by the photographer’s fascination with spectacle. Weegee’s Hollywood portraits, much like his earlier reportorial work, comment on a world increasingly held in the thrall of images. As I was walking through the exhibition, I began to think that we are now living in a time that perfectly reflects Weegee’s interest in naked, blatant reality and in the warped dreams spectators crave. Last year, I wrote briefly about one of the images taken of Donald Trump at an election rally in Butler, Pennsylvania, moments after he survived an assassination attempt. In the photograph, taken by Anna Moneymaker for Getty, we see the President on the ground, a dark-red rivulet of blood dripping down his deeply tanned face, his hands held up as if in prayer. It struck me, looking at it again, that the image traverses the same valley explored by Weegee’s work. It is both unabashedly real and, almost despite itself, inflected with the kind of near-grotesque celebrity obsession our culture is mired in. What is our world now if not a fun-house mirror through which we view not events but the images that have come to replace them? ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com