Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Martin Scorsese has the best curveball in the business. His 2013 film, “The Wolf of Wall Street,” based on the true story of a large-scale financial fraudster, is also his wildest and wackiest comedy, closer in inspiration to Jerry Lewis than to Oliver Stone. His modern-gothic horror-thriller “Shutter Island,” from 2010, is primarily a refracted personal essay about his childhood spent watching paranoid film-noir classics in the shadow of nuclear war. And now his forthcoming film, “Killers of the Flower Moon,” his first attempt—as an octogenarian—at a Western, is essentially a marital drama akin to Stanley Kubrick’s final film, “Eyes Wide Shut.” It borrows more from such intimate psychological dramas as “Phantom Thread,” “Suspicion,” and, yes, “Gaslight” than from any of the Western classics of John Ford. In other words, the first of the mysteries that Scorsese’s new film poses isn’t in the plot—it’s the mystery of its own genesis.

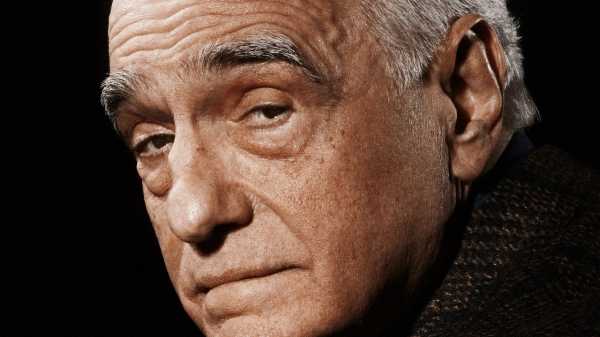

When I met Scorsese several weeks ago, I told him, before we got started, that I do very few interviews, because, well, I have a director’s films, and, if watching them doesn’t give me enough to think about and to write about, then I’m in the wrong profession. That said, there was much that I wanted to know about Scorsese, not least because of the paradox of his artistic position: he directs extraordinary movies on hundred-million-dollar budgets yet makes them deeply personal and packs them with artistic flourishes—spectacular camera moves, intimate observations, dramatic shocks, and moments of performance—that are as daring as they are distinctive. I wanted to ask about his methods because I’ve long felt that a huge part of the art of directing is producing—that the originality of a finished film usually has its roots in the distinctiveness of its director’s approach to the systems and methods that get it made.

I’d seen something of Scorsese’s behind-the-scenes originality in Jonas Mekas’s documentary about the making of Scorsese’s 2006 gangland drama “The Departed”—the movie for which Scorsese finally won the Oscar for Best Director, after five previous nominations ended in disappointment—and which heralded his great outburst of work in the past decade and a half. I’d also seen it in “The Wolf of Wall Street,” in the way that Scorsese took the increasingly commonplace technology of C.G.I. and proceeded to use it like a painter. But the part of his process on “Killers of the Flower Moon” that I was most curious about involved the subject matter. Set in Oklahoma in the nineteen-twenties, “Killers of the Flower Moon” is based on the nonfiction book of the same name by David Grann, a colleague of mine at The New Yorker. In the movie, Leonardo DiCaprio plays Ernest Burkhart, a white man who marries an Osage woman named Mollie (Lily Gladstone), under the direction of his gangster-like uncle (Robert De Niro), as part of a wide-ranging and murderous scheme to pry away the wealth of the Osage Nation, on whose territory oil has been discovered.

One of the common frustrations of watching movies adapted from books is the inevitable abridgment of the source material. Reading a book several hundred pages long takes many more hours than watching even a longish feature, and, often, one can sense an adaptation’s compression and gaps without having read the book. Scorsese’s new film is colossal—three hours and twenty-six minutes—but even that duration could never encompass the plethora of incident that Grann delivers in his fascinating, horrifying book. Scorsese escapes this dilemma with a move of almost Houdini-like ingenuity, zeroing in on something that even Grann’s voluminous research couldn’t shed much light on: what was that couple’s relationship like? Thanks to this change in emphasis, the task of writing the script became not one of condensation but one of expansion—of filling a historical gap by means of imagination. And the way in which the couple’s relationship is reimagined, as Scorsese made clear to me, embodies his own grappling with the underlying morality of Grann’s tale—a responsibility to place the Osage people at the center of the story that turned out to shift the very aesthetic of the movie.

Almost all directors are also actors; they just happen to reserve their performances for their cast and crew. Some also perform in movies, their own or those of other directors; Scorsese has done both, albeit in incidental roles. In “Killers of the Flower Moon” he appears in a small but crucial dramatic role, a performance that is far more powerful than a Hitchcockian wink or a cameo to please connoisseurs. Scorsese won his Oscar at a time when the studios had already become inhospitable to his kind of large-scale yet artistically ambitious filmmaking, and the ensuing rise of superhero movies and other primarily youth-centered I.P. franchises made matters worse. Scorsese has leveraged his eminence to take a leading role in advocating for studios to both invest in the preservation and distribution of classic movies and release new and substantial movies by ambitious directors. In effect, he has become the face and the voice of the cause of cinematic art—past, present, and future. No spoilers, but, when he acts in “Killers,” he nonetheless speaks for himself and speaks, too, for the cinema at large.

In person, Scorsese has a lot to say, and the fascination of what he says is heightened by his way of saying it. Just as a scene in a movie may be made of dozens of shots of diverse durations, assembled in various ways, and often ranging far in time and space and tone, so Scorsese speaks in a free-associative, quick-cut, montage-like manner that is entirely his own, building drama as the details accrete and connect with verbal counterparts to cuts, dissolves, superimpositions, and other kinds of cinematic punctuation. His conversation is the image of a mind in motion, ranging freely between memory and perception, between practical specifics and ideas, between firsthand experience and notions gleaned from watching movies—all infused, like his films, with purpose and passion. Just as “Killers of the Flower Moon” was the fastest three and a half hours of my moviegoing life, my conversation with Scorsese about it was the fastest hour of conversation I’d ever experienced. Our discussion has been edited for length and clarity.

There’s something special about “Killers of the Flower Moon.” You always tell good, moving, passionate stories, but here I felt like you were doing something more than telling a story. I felt like you were bearing witness. Did you have that feeling when you were making the film? Was that part of what went into the project?

Definitely. And I think it goes back to a time in ’74, when I had this opportunity to spend some time, only a day or two, maybe two days, with the Oglala Lakota (Sioux) tribe, in South Dakota, and I was involved with a project that didn’t work out. It was a traumatic experience, and I was so young I didn’t understand. I didn’t understand the damage and the poverty. I grew up with poverty in another way, which was working-class men and women on Elizabeth Street and Mott Street and Mulberry, but we also had the Bowery. So I grew up with that poverty. But I never saw anything like this, and I can’t describe why—it was hopeless. I met some Native Americans again in L.A. at the time, and we talked about another project, and I saw too that this incredible fantasy that we had growing up as children was something that—even despite the wonderful attempts at righting the wrongs of the Hollywood films with “Broken Arrow,” “Drumbeat,” “Apache,” “Devil’s Doorway”—all the films that were pro-Native American, there were still American white actors playing the Native Americans. But the stories were balanced toward not only who had right on their side, but also a respect for the culture, particularly in “Broken Arrow,” I thought.

But, in any event, no, I was always aware of poverty, and I always felt I was witness to it there only for a couple of days. But culminating in the end of the Western with Sam Peckinpah, there was a new territory then: how are we to think, what are we to make of all this in terms of the Native American experience? Are they really gone? In a way, as children, we thought, Well, they’re with us, but they’re like us now. We were children and, I think, meant to think that way of the forced assimilation, to a certain extent, of the Native populations. But I didn’t know. When I got out there and I saw what it was, it was different.

But from 1974 to now—it’s forty-nine years. Had you been thinking of a project involving Native Americans for the entire time?

I stayed away from it. I stayed away from it because the shock was so strong. Somehow it had to be the right story, and that’s taken a long time.

How did you find David Grann’s book? How did it come to you?

Oh, Rick Yorn gave it to me. Rick is my manager, and also Leo DiCaprio’s manager. And, yeah, the idea of the flower moon—the flower moon is feminine and we had just worked on “Silence,” and the moon images and the sense of Jesus as the feminine side of Jesus rather than the masculine side is really important. And so, for me, the flower moon, the feminine, but the “killers of the flower moon,” the clash of that, and this landscape, which I only had in my imagination—I’d never been out to the prairie. When I got out there, we were driving for so long on one road, and I wondered why we were going so slowly, and I looked at the—it was, like, forty-five minutes—I looked at this speedometer, we’re doing seventy-five, and I realized this place never ends. And on either side there were no trees. You really couldn’t tell how fast you were going.

What you did with the book, I mean, not that I would ever want to teach, but if I were teaching a class on adaptation, I would show people your film and I’d have them read David’s book, because your transformation of the book is, to me, one of your many great achievements, because you have everything that’s in the book, almost everything that’s in the book, almost all the salient details of the horrors, in the film. But you reverse the perspective.

Yeah. Leo and I wanted to make a film together about this whole idea of the West and all that sort of thing. And he was going to play Tom White, the F.B.I. agent. And so I said, I’m thinking, how are we going to do this? Because I’m just, not to be glib, but Tom White, in reality, was a very strong-willed man. Very, very, very disciplined, moral, straightforward. And laconic. Hardly said anything. Didn’t need to say much. Now, Leo likes—I told him many times, I said, Your face is a cinema face. I said, You can do silent films. You don’t need to say that or this, just your eyes do it, move, whatever you do, he just has it—but I do know he likes to speak in films.

Then I’m realizing, too, who are these people? I said, These guys come in from Washington, and the moment they get off that train, the moment they enter that town, you look around and you see Bob De Niro, you see so-and-so—“I know who did it.” The audience is way ahead of us. I said, It’s, like, we’re going to watch two and a half hours of these guys trying to find things. That’s a police procedural. In the book, it works; in the book, it works. But a police procedural, for me, I’ll watch it, but I can’t do it. I don’t know how to do it. I don’t know how to do the plot. I don’t know where to put the pen. And so I said, What the hell are we going to do here? So we tried and tried and tried. Our script was over two hundred pages, and one night we had a big reading: myself and Leo and [the co-writer] Eric [Roth] and my daughter, a number of people. The first two hours, we were moving along. The second two hours, boy, is this getting a little long in the tooth, as they say. It was just getting to be—we really ran out of energy in the story, and I wanted to tell more and more of the story, and I wanted to do more digressions, to go off in tangents, so to speak, what seem like tangents, but are not.

But at the same time, luckily I had gone out to Oklahoma a few times and the first thing I did was, I was very concerned about meeting the Osage Nation to see how we could coöperate together. I found that yes, they were concerned about trust. I got them to understand that I wanted to do the best I could with them and the story, and that they could trust me, I hoped. And they began to, but I also understood why they don’t. I totally get it. And that’s the story. Now here, what really is the story is that you have trust in a marriage, right? O.K., there are different levels of it and there are aspects and mistakes and things, but there’s trust. Well, what I was learning from the Osage was that all the families are still there. The Burkharts and the Roans, Henry Roan. What we were told by their descendants was, Don’t forget this, that Ernest and Mollie were in love. Why the hell did she stay? Not why did she stay with him? How did she stay with him? Why one person stays with another, we don’t know. “How” is another issue, another way into the story. The “how” is deception, self-deception; the “how” is love stronger than what she dares think he is doing. So this was a coverup, and yet she trusted. And so this love story, this love story. And we had met with Lily [Gladstone] through a Zoom because [the casting director] Ellen Lewis showed me Kelly Reichardt’s “Certain Women.” Lily was extraordinary in it. And then Leo and her met on the Zoom because he was very concerned about who are we going to get to play this part? Obviously, she has to be Native American, and we wanted the Osage approval. They approved her, and, before they approved her, Leo had this conversation with her on Zoom, and as soon as the Zoom call was over he said, “She’s amazing.” I said, ”Yeah, for many different reasons.” I think a lot of it you can see in the film; she has integrity, a sense of humor.

There’s a profundity to her and there’s a sweetness, at times, of face. We felt confident that she knew more than us. She just knew it, meaning she knows the people, she understands the situation, she understands the delicacy of the confusions and, I think, the trespasses, so to speak. But in any event, after doing the reading, a week later, Leo came to me and—we still had this in our head, that they’re in love. And the reality was that she didn’t leave until after the trial. We had scenes in there, the F.B.I. guys—or the Bureau guys—were saying, “How is she still with him?”

They actually said that. We have the court transcript. She’s still there in the court. She’s in the court. Doesn’t she get it? But there was something about him and her together, and then she left him after that. And we said, Well, what was that about? And I said, What if that’s the story? And Leo came to me and said—so we tried to build it in within the context of somebody else playing Ernest, and Tom White dealing with, again, the police procedural, but it overwhelmed it. The procedural overwhelmed the personal story. And Leo came to me again, he came to my house one night, a week later, and he said, “Where’s the heart of the film?” I said, “Well, the heart is with her and Ernest.” He said, “Because no matter what, if I’m playing Tom White, we deal with the iconic nature of the Texas Ranger.” We have seen that; it’s good. Does he need to do it? How would I do it any differently? I tried. I couldn’t find a way. So he looked at me and sat down and said, “Now, don’t get upset.” He said, “But what if I play Ernest?”

So it was his idea to do it. Wow.

I said, “If you play Ernest and we deal with the love story, then we’re at the very heart of it. We’re in the the day-to-day.” I said, “You realize, of course, that means we go in the center of script, rip it open and change everything and tell the studio you want to play the other guy, and we’re going to go this way, and Lily’s great, and we’ll rewrite the whole thing,” which is what we did.

But “rewrite” is the wrong word. We constructed it all. Eric [Roth], me, a couple of friends helped. That’s what we had done with “Casino,” too, Nick Pileggi and I, we worked from transcripts. And so I would say, “That’s great over here.” And then another guy would say, “Hey, why don’t we put this in?” And so, cobbling and pushing and shoving, I mean, until we went into rehearsal, and then, even in rehearsal, we just kept working on it and working on it, and we had a lot with the Osage themselves, they would say things, and one guy, Wilson Pipestem, who was a lawyer, a really terrific guy, Osage, he was very concerned at first. He looked at me and said, “You don’t understand, we have a certain way of life.” And he’s a very strong lawyer, an activist, and he pointed out and said, “We grew up this way, we grew up that way”—he was giving me examples of things in the midst of, not a lesson, not an argument against me, but an argument for himself and for his people, saying, “This is what we are, you don’t understand this. For example, when I was young, my grandmother would be in the house and all of a sudden this storm would come up and I’d be running around and she’d say, ‘Nope, sit down, sit down, let the storm flow over us, the power of the storm. It’s a gift from God. It’s a gift from Wah’Kon-Tah. Let the storm—don’t move, just absorb the storm.’ ” And he said, “That’s the way we live.” So I wrote it down. Grab from here, grab from there. And there was the end of the scene, the dinner scene with Mollie and Leo, which we had written where she said, “Would you like some whiskey?” and they drink and she drinks more than him, but she doesn’t get drunk and he does. And I said, “We could do a great scene.” I said, “But there’s something—what if the rain hits? What if the storm happens, without making it too ominous, the storm, but it’s the power of the storm, the beauty of Wah’Kon-Tah, the gift of the storm. And, in order to do that, you have to be quiet. You can’t be your little coyote self.” And she controlled him that way, and he just waits.

So that’s the way it was constructed. We had fun with that because we were always finding new things, because somebody would go by and say something, or [the producer] Marianne Bower would find out a great deal. She was our connection with all the people. She’d work with the different departments, different Osage technical advisers for different departments, and, well, “So-and-so said this and so-and-so said that.” “That’s interesting. What is that?” “Well, you know what they normally do: the youngest member of the family walks over the coffin of the eldest who died.” Well, that’s got to be, it’s got to be. We have to do it.

So then the funeral scenes got bigger. So, in a way, what I mean by “got bigger” was that I—we even had more, but we had to narrow it down, narrow it down. Then I had the—coming from Sicilians, one of the key things, I grew up with a lot of the old people dying off. So I grew up in a lot of funeral parlors, and the old Italian ladies, the old Sicilians in black, it’s like “Salvatore Giuliano,” remember? “Turiddu!” and she screams on her son—that’s who we grew up with. And the son’s holding the mother back and she’s throwing herself in the coffin. I said, “They were talking about the wailers and the mourners.” I said, “They have mourners.” They have people who cry. So we got to do that. And when we did it, I found that—they said, “We do it in front of the house.” I said, “Great.” And I said, “Well, let’s get a wide shot of it from way above.” And there was the house, there was nothing behind it, and there were these three figures, and they’re wailing, and the way it sounded, well, that’s great. “Don’t you want a tighter shot”? I said no. He said, “I got a tighter shot, it’s maybe from—” I said, “No, the shot is up here. I think it’s up here because they’re wailing out to Wah’Kon-Tah. We see it all. And there’s this little house, pathetic human beings. We’re all as we are, and we’re just wailing and you barely hear it.” So this is the way it was.

Your description of your discovery of the overhead shot reminds me of one of the things that’s miraculous in masterworks of large-scale filmmaking, which is that it’s like you’re painting a painting with a paintbrush at the end of a crane, but you’re not driving.

No, I’m not driving it. I would like to, I’d like to drive the crane, but then I’d get into all kinds of trouble. But no, I don’t want the technology to limit me, meaning to get too hung up on the technology. I’ve always been fighting that for years. That’s why I had good relationships with a number of different directors of photography, Mike Chapman and certainly Michael Ballhaus, others I’ve worked with that were terrific, but we only did one or two films together. But often I would find that many D.P.s love the equipment and the equipment gets in the way.

I had a shock of a lifetime when I saw something that was put up online soon after the release of “The Wolf of Wall Street,” which is a video made by Brainstorm Digital, a company that did some post-production work on the film. And what they showed was the footage as it appears in the film, and then the raw footage from the camera and how, by means of digital technology, by C.G.I., things were—a wedding scene was lifted physically off of one site and placed on another completely different background.

Oh, yeah, we did something. Yes, yes, yes.

Did you find yourself needing to use a lot of C.G.I. in the making of “Killers of the Flower Moon”?

No, not really. Except for straightening out some landscape. For example, certain trees that weren’t quite right, supposedly.We were told those trees don’t necessarily belong in this part of the ground, whatever. No, we found that what [the production designer] Jack Fisk did with Pawhuska, where we shot, to make it look like Fairfax— Fairfax was about forty-five minutes away—it was like a studio. It was like we were literally going to these places. We had the storefronts reconstructed. It was like going back in time, really. We were spending a lot of time in 1921 and ’22.

One of the things about this film, and, for me, your recent run of films, including “The Irishman,” is that they are ferociously political. I really get a sense of “The Irishman” as, Let me show you what’s lying underneath this respectable society, and, with “Killers of the Flower Moon,” it’s like lifting up the lid and saying, This is your American history. This is what you didn’t learn in school. This is what our society now is built on and doesn’t dare look in the face.

Exactly. Exactly. Maybe because where I came from, I saw it on street level, I think. A lot of it has to do with believing that you’re right, believing you deserve it. And that’s what I’ve been becoming aware of in the past twenty-five, thirty years of the country based on people who formulated the country, white Protestant—English, French, Dutch, and German. And so that country was formed that way with that kind of thinking. It’s European, but not Catholic, not Jewish, but the work ethic of the Protestant, which is good. It’s just that that was the formation. And then the political and power structure came out of that and stays with that. It just stays with it. I also saw and experienced people close to me who were basically pretty decent, but did some bad things and were taken advantage of by law officers. So I grew up thinking there’s no lawman you could trust. There was some good police, there were some good cops on the beat, nice guys. Some were not. But, from my father’s world, from his generation, it was a very different experience. But this issue of—I really admire the idea of people who really get into politics for public service and are really public servants. That’s really interesting. If they really serve the public.

Could you make a film about one?

I don’t know. One who could try, one who could try to be a good public servant. It reminds me of the line in “Black Narcissus.” The Mother Superior tells Deborah Kerr before she goes to India: Remember, the leader of them all is the servant of them all.

I have the feeling that something changed in your work after “The Departed,” after you won the Oscar. Not that awards really matter, but that, at that point, it was like you had nothing else, whether consciously or unconsciously, nothing more to prove. And you then made a film that I consider one of your best and one of your, in the most positive sense, craziest films, “Shutter Island.”

Yeah, the people are split on that one. But I like it, in the sense that every line of dialogue could mean an infinite number of things. It was really quite interesting for me, I really wanted to do it. Winning the award was—don’t forget, it was thirty-seven years before an Oscar for Best Director, let alone Best Picture, which was a total surprise to me. But it’s a different Academy from when I was starting. But, for me, that award was, it was inadvertent. I had made “The Departed” as a sign-off. I was leaving and just going to make some small films, I don’t know. And it just happened that “The Departed” clicked. And it was a very difficult one to make, for many different reasons. That’s a whole other story. But we fought our way out of it—through it, I should say. Through it, out of it. And, when I finally threw it up on the screen, people liked it. I don’t mean I didn’t think that it was good or bad. I just felt we had accomplished something. I didn’t know it was going to be that way. I had no idea. And my next film was going to be “Silence.” That was the idea. But what came in between was “Shutter Island.” There were issues there. I did feel something—let’s make, O.K., now I can—let’s try and make another movie. And I got the script and I just fell in love with the script. Then I didn’t realize, until we started working with the actors, the different levels, and I knew the levels were there, but how to perceive—how to shoot it, how to perceive the images, and also how to direct the actors.

But the thing about it was that in a way, after “Departed,” it was like I knew I could not make films for the studios anymore, because at that time—there’s no ill will between us and the people who were at the studio at the time—but, even to this day, they wanted a franchise film, and I killed off the two guys. They wanted one to live. I didn’t want to make films that way. And I realized there was no way I could continue making films. And so everything since then has been independent to a certain extent since “Shutter.” The guy who took care of me was [the Paramount Pictures C.E.O.] Brad Grey. He came in, Brad gave me “Departed,” and he agreed on “Shutter.” And so then he passed away. And, since then, it’s really been independent. There’s no room for me to make films through the studios that way anymore.

Well, that’s been my hypothesis: that an entire generation of younger filmmakers found their second wind with independent producers, whether it’s Wes Anderson or Sofia Coppola or Spike Lee.

Yeah.

But, from your generation, you are the person who—the studio was holding you back in a certain sense. Not that you made bad films, you made wonderful films. But I kind of always felt there’s more. There’s a—not compromise—but there’s a wall that a filmmaker hits, any filmmaker hits when they’re working for the big studios.

There’s no doubt. And my thing was to explore that. And in some cases—in the case of “Last Temptation of Christ,” I had a deal at Universal. I owed them some movies; that became “Cape Fear” and “Casino,” and that was it. But by the time we did “Kundun” and “Bringing Out the Dead,” it was over. It was over. We were declared gone, “Bringing Out the Dead” only played for a few weeks. And it was a Paramount film. And that was the end. And again, [my agent, Michael] Ovitz came and kind of helped me and put together “Gangs of New York” with Leo, with [Harvey] Weinstein, and all of them. That became a whole other period of my life. I was glad when it was over, but I was obsessed with “Gangs.” I never really even finished it in my head. And I just said, O.K., this obsession is over with. I still haven’t, at that point, hadn’t cracked the script for “Silence.” So I was ready to do a movie. I wanted to work and make a film, and they had this thing called “The Aviator.” They didn’t tell me what it was about. And so I started reading it, don’t tell me it’s Howard Hughes, because Spielberg, Warren Beatty want to do—but then I kept reading it. It’s the different Howard Hughes, it’s the early Howard Hughes. He flies and he’s—but right here, in the meantime, he can’t touch a doorknob.

That’s interesting. So we did that. And, even that, that was fine. That was a terrific shoot. The editing was good, but the elements involved in the distribution caused some serious problems toward the end. I had some very, very ugly—and I decided at that point, you can’t make films anymore. If this is the way I’m going to have to make them, it’s over. And so I said, I wanted to make this. I found the script of “The Departed” and I liked the idea and I said, “Let’s just make this in the streets and let’s do something.”

But that became—it turns out it was Warner Bros., which was one of the distributors of “Aviator” that we had some arguments with. And they said, “Don’t worry, we’ll take care of you.” But, in the meantime, it was difficult. And so, after that I said, “No more.” And so we went into “Shutter Island,” but I was able to make “Departed” pretty much the way I wanted to. But it was a knockdown, drag-out fight all the way from Day One to the end. So by that point I realized, if that’s the way you’re going to make a film, there’s no sense anymore. So it was going to be independent films and it was going to be going into “Silence” and that sort of thing.

So did you think you were going to scale back and work on very low budgets with seven people in the street?

Yes. Yes.

Are you still tempted?

I think, let me put it this way, it’s into my head. Seven people could be seventy, but it’s got to feel like seven, because, quite honestly, I’m short. I’m old now. Try to get in the room with the lighting and all the cable. I have to have an assistant in front of me, taking me. I would love to be able to have the freedom of the smaller crews again, a sense of freedom. But in the case of “The Irishman,” for example, out of the question, because of the trucks, because of the C.G.I., and Bob [De Niro] and me, I was seventy-five. Bob was seventy-five, Al [Pacino] was seventy-seven, Joe [Pesci], I don’t know what age he is. I mean, at a certain point, by the time we all get on set, they’re good for a certain amount of hours.

And if you want to say, “Hey, we’re going to go down the block and shoot another scene, we’re going to move all the trucks,” they need sleep. So we were kind of locked in there. But with “Killers of the Flower Moon,” by having Pawhuska to ourselves, that was quite something. Adam Sumner’s a brilliant assistant director. He works with Steven Spielberg and Ridley Scott. His staging is wonderful, and the background stuff—I would say, “O.K., they’re going to be coming down the block here, we’re going to track this way,” and, of course, it’s 1921. So the background, costumes, horses, you need people doing things. It’s not like shooting in New York, but we had the control. It was like a studio. We had the control. And that, in a funny way, made it feel like we were making a smaller picture.

And we had such devotion from the Osage, from all the people working behind the camera to get the costumes right. I chose them. You could see it with [the costume designer] Jackie West. I sent black-and-white pictures everywhere, and drawings. I would circle a tie or a collar or a shoe. They would bring me stuff from the Osage and I’d circle certain things. They’d tell me what’s right and what’s wrong for certain. But, primarily, I mean buttons. I would go on—every place in the film, all the men’s and women’s costumes had gone through me, through to Jackie, from historical photographs and from films like “The Winning of Barbara Worth,” which I saw one night. My wife was in the hospital, it was on TV on TCM. And I think Gary Cooper’s wearing the goggles in the car. It’s a silent film. And so we had the goggles. Or “Blood on the Moon,” which I looked at again last night because I want to do something on TCM with it. “Blood on the Moon,” the costuming there and the brooding nature of the way they move. And Robert Mitchum, Charles McGraw, Robert Preston. Very, very important influence for this picture. So it felt free, and maybe in a way, too, because we weren’t in L.A., we weren’t in New York. There wasn’t anywhere to go. You’re in a big house that I had rented and you go and make the movie, you’re not going to Tulsa; you have night life in Tulsa. I was in Bartlesville, where Terry Malick grew up.

So you’re all focussed together and there’s essentially nothing to think about but the movie.

The picture. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com