Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

“Linda Evangelista Photographed by Steven Meisel” is not the book we’ve been waiting for, but it will have to do for now. A hefty compilation from Phaidon of the work Meisel did with the model between 1987 and 2011, it sidesteps a long-overdue summing up to focus on one of Meisel’s most productive collaborations. Like Richard Avedon before him, Meisel was not always the first to photograph a given model, but he was often the one who realized her full potential and was instrumental in her success. He and Evangelista hit it off on a shoot for American Vogue, but it was their work together for the more adventurous Italian Vogue that really clinched the relationship. Vogue Italia’s visionary editor, Franca Sozzani, was Meisel’s shrewdest and most indulgent champion. When she took over as editor-in-chief, in 1988, she brought Meisel in to do covers–nearly every one of them, for the next several decades—which are collected in the 2009 book “Three Hundred and Seventeen & Counting,” and peppered throughout “Linda.”

Linda and Steven, circa 1992.

With Vogue Italia as his main platform and playground, Meisel was free to experiment, often at great length. One of his wittiest extended narratives, “Makeover Madness” (also excerpted throughout “Linda”), ran eighty pages in the July, 2005, issue. In the series, Evangelista is the lead in a drama set in the offices and operating rooms of plastic surgeons and in the luxury hotels where patients gather to recover. Meisel is at his slyest and most meticulous here, staging incongruous scenes on operating tables with models in full makeup and evening dress with jewelry, handbags, heels, and “bloody” gauze. The influence of Luis Buñuel and David Cronenberg permeate the shoot, but the project is pure Meisel: wicked satire delivered as brilliant fashion photography.

Vogue Italia, July 2005.

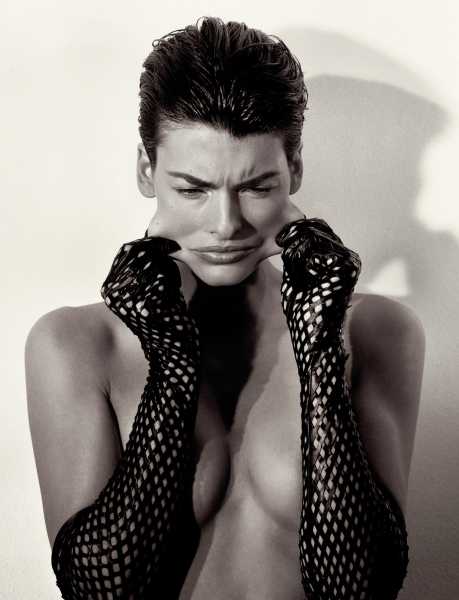

Evangelista stands out among Meisel’s cast of characters in part because she’s so perfectly, elegantly blasé, whether there’s a scalpel slicing into her thigh or a bandage wrapping her head. Talking with William Norwich in “Linda” ’s chatty introduction, she says she can often anticipate Meisel’s adjustments and mood shifts. Like all great models, Evangelista is malleable—sultry, sincere, anxious, ecstatic—and in a world of her own, or in worlds of the imagination that she and Meisel share. Here she is in a party scene from “La Dolce Vita,” in a Central Park idyll right out of Woody Allen’s “Manhattan,” as Katharine Hepburn between scenes or as Gina Lollobrigida on a street in Naples. She might be the girl next door, but she’s never Barbie. On camera, she’s a medium inhabited by spirits that Meisel knows just how to evoke.

Vogue Paris, June/July, 1989.

Vogue Italia, October, 1993.

Meisel prefers not to talk to the press and avoids most interviews. When he tells Norwich, “I was just holding up a mirror to society,” it sounds like he’s quoting something someone said about him, though not inaccurately. He’s more interesting when he’s talking about process and what goes into making a picture of a disappointing dress. “I think it’s helpful if the clothes are inspiring,” he says, “but it doesn’t really matter. That’s part of our job—to make the clothes look great.” Evangelista underlines the point: “We understand the assignment,” she says. Understanding the assignment is what has kept Meisel grounded and the work vital and charged. He lost his Vogue Italia cover slot when Sozzani died, in 2016, but his work with Edward Enninful at British Vogue has kept him in the conversation, and he remains the most inventive, intelligent, and original fashion photographer around. But where does he go from here? The obvious next step would be a full-on retrospective and accompanying book, but Meisel has never seen such a project through. (Full disclosure: one catalogue that was in the works but never materialized would have included an essay by me.) Like so many living artists, Meisel may be reluctant to see his work summed up and put aside.

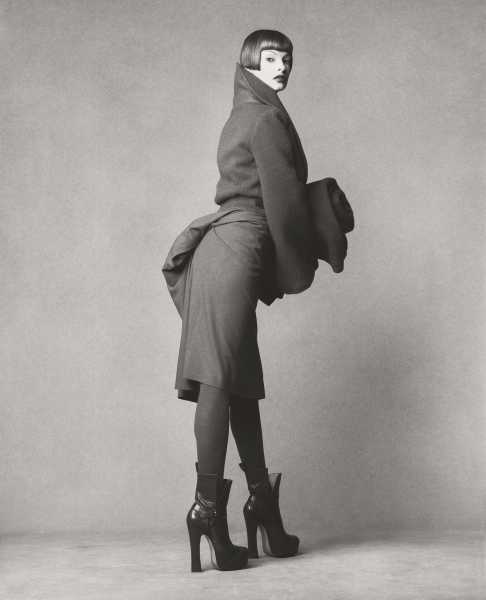

Vogue Italia, March, 1994.

Vogue, May, 1993.

Meanwhile, we have Meisel samplers such as “Linda,” the exceedingly rare “Three Hundred and Seventeen & Counting,” a stack of Versace catalogues, and “Sex,” a seriously underrated Madonna collaboration, which was recently reissued, in conjunction with Saint Laurent, at twenty-two hundred dollars a copy. (More than forty choice images from the book, signed by Meisel and Madonna, are currently on view at Christie’s in the lead-up to an auction on October 6th.) “1993,” an exhibition dedicated to one year of Meisel’s work that opened in Spain last November, unfortunately did not travel, but the catalogue to that show, designed by Fabien Baron, offers an especially juicy slice of Meisel’s career—and suggests just how difficult a real retrospective would be. Evangelista is all over the book, but so are the similarly malleable and clever Kristen McMenamy and Stella Tennant. Like Avedon, Meisel was interested in models with character and characters he could turn into models, if only for a day. In addition to the supermodels (including Naomi Campbell, Christy Turlington, and Claudia Schiffer), he features Betty Catroux, Loulou de la Falaise, Anh Duong, Isabella Blow, and Barbra Streisand. The presence of men, both models and civilians, helps give us a fuller sense of a queer eye at work. Here again, Meisel goes for personality and quirk, and he’s especially frisky when it comes to gender fluidity. His photograph of the willowy Vogue editor Hamish Bowles in nothing but a corset is one standout example of how his pictures of men toy with received notions of masculinity. Meisel was at his canniest and most provocative when he was contributing regularly to L’Uomo Vogue and Per Lui in the nineteen-nineties. While we’re waiting for a retrospective blowout, a volume titled “Meisel: Men” would help fill the void.

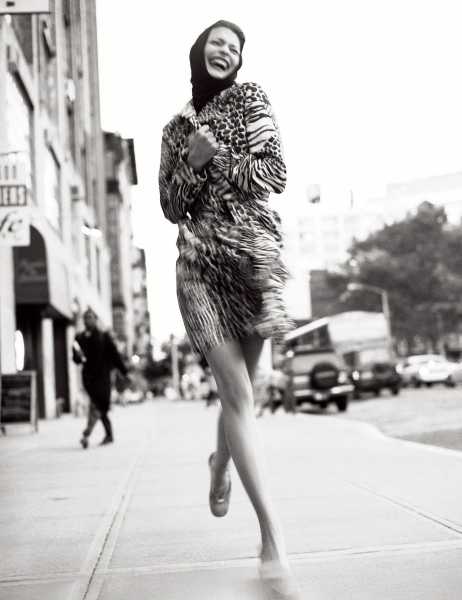

Vogue Italia, February, 1989.

Barneys New York, Fall/Winter, 1991.

One model. One year. Both “1993” and “Linda” start the task of whittling down Meisel’s astoundingly prolific career to a manageable size. But the prospect of more piecemeal projects should be as frustrating to him as it is to his impatient audience. Meisel’s already made history. Now he needs to shape and claim it.

Dolce & Gabbana, Spring/Summer, 1996.

Sourse: newyorker.com