Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

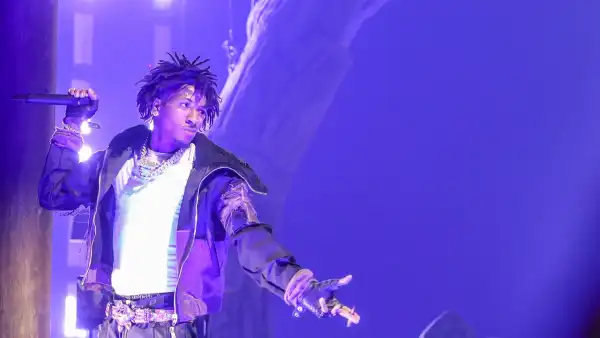

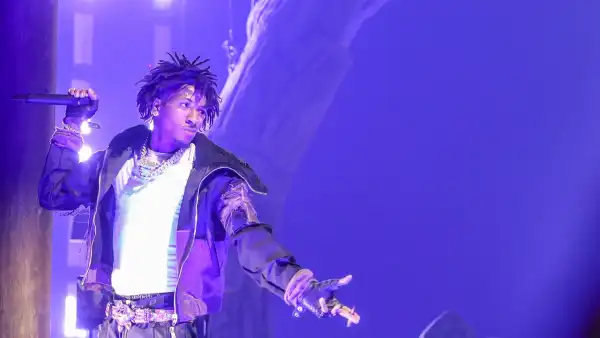

Few happenings in music lately have suggested greater pandemonium than this: the initial prominent headlining tour by YoungBoy Never Broke Again, a rapper with remarkable skill and intensity, celebrated by his particularly young and boisterous fanbase as NBA YoungBoy. The tour commenced last month, featuring two sold-out performances at the American Airlines Center, in Dallas, home of the Mavericks; shortly afterward, videos showcasing excited audiences began to spread online. Not all of the fervor has been positive: during a show in Kansas City, a fourteen-year-old patron was videotaped attacking a sixty-six-year-old usher, leading to charges of felony and misdemeanor assault; shows in Chicago and Detroit have been called off, with scant explanation. Yet, when the tour reached the Prudential Center, in Newark, last week, the atmosphere was celebratory, albeit disorderly. The arena teemed with supporters donning black YoungBoy T-shirts and waving slime-green YoungBoy bandannas: they shunned the seats, jammed the pathways, and recited every lyric. The sole individual who seemed unaffected by the frenzy was the composed and rather stately figure who ignited it. YoungBoy arrived on the scene encased in a coffin that was lowered to the stage, and he delivered his verses with the sadness and resolve of someone aware that, inevitably, he would revert to his starting point, but no longer upright.

At the inception of YoungBoy’s journey, he seemed fearless. “Don’t address me like I’m a youngster,” he scoffed, in a track released in 2015, when he was merely fifteen. He appeared lean and grave, marked by indentations on his forehead, later revealed to be the consequence of a halo brace secured to his skull after fracturing his neck wrestling with friends at age four. He also demonstrated fervent devotion to his city, Baton Rouge; in the music video for “Murder,” from 2016, he and his peers posed in a modest dwelling, flashing some cash and a considerable amount of weaponry. The lyrics he vocalized—“That stuff you’re saying ain’t scaring us / Forget your approach, you can’t see us”—were notable for his drawling Louisiana tone, and his transition between spirited rapping and a somber croon that hinted at qualms beneath the swagger. “I dread people, and I’m quite timid,” he confided, in a hushed tone, during an exceptional 2023 video interview with Billboard. “People are harsh. It seems we lack control.”

Over the last decade, YoungBoy has put out an impressive volume of music: more than three dozen complete projects, including eight in 2022 alone. Concurrently, he has cultivated a substantial online following, particularly on YouTube, without achieving a major hit; “Make No Sense,” from his acclaimed 2019 album “AI YoungBoy 2,” reached No. 57 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart, yet it has been streamed over half a billion times on Spotify. Hip-hop triumphed globally long ago, but the Newark spectacle served as a reminder that the genre is still not fully integrated, partially because it has preserved its special connection to struggling Black communities like YoungBoy’s upbringing. Despite his fame, he maintains few affiliations with the wider realm of popular music, affording the show both the closeness and zeal of an underground affair. Green lights illuminated the stage, and the crowd chanted in unison as YoungBoy’s lyrics repeatedly revealed the transformation of steely determination into something more sensitive: “They persistently drag me, I compete fiercely, they fear me / I can’t hardly—can hardly rest, or even breathe.” He possesses a gift for lyrics that are strikingly confessional, often in dual respects simultaneously.

Many individuals consuming YoungBoy’s unending stream of new songs have also been following updates on his various conflicts and court cases. At seventeen, he was implicated in a drive-by shooting. (He admitted guilt to aggravated assault with a firearm and received a suspended sentence.) At eighteen, he faced accusations of assaulting and abducting his girlfriend, an allegation seemingly supported by surveillance footage. (He admitted guilt to a misdemeanor and was given probation.) He has been in conflict with multiple rappers, some of whom were subsequently shot and killed, and despite YoungBoy never being charged regarding these fatalities, followers have been inclined to suppose that the threats within his lyrics mirror actions he has actually undertaken, or might undertake down the road, if his adversaries aren’t cautious. By the time the Billboard videographer engaged with him, he resided not in Louisiana but in snowy Utah, striving to avoid trouble: under house arrest, with a limit of three visitors at a time, awaiting trial concerning federal gun charges. He was found not guilty in one instance and pleaded guilty in another; last December, he received a sentence of twenty-three months in jail and five years of probation, although he was released from federal detention earlier this year. In May, President Trump issued him a pardon, relieving him of his probation, whose stipulations might have rendered it impossible for him to organize a major tour akin to this one. On the Fourth of July, he launched an album titled “MASA,” which represents Make America Slime Again. (It is among three YoungBoy releases so far this year.) In hip-hop, “slime” can serve as a diverse term of friendship, and YoungBoy’s title functions as both a boast and a Presidential salute. The album lacks the distinct sharpness or lively vitality of his best material, but it possesses ample charisma and a few unanticipated shifts, none more unanticipated than “XXX,” which borrows its chorus—“Sex and violence!”—from an old punk band named the Exploited, and which presents an abrupt political endorsement. “Whatever Trump’s doing, lady, it’s beneficial for the youths,” YoungBoy declares, although the remainder of the album implies that he is still quite interested in engaging in mischief.

YoungBoy’s stage name becomes less appropriate each year: he reaches twenty-six in a few weeks, and he is the father of at least ten offspring with eight different women. (A particularly charming and melodious track known as “Kacey Talk” is named for one of his sons, not because the lyrics address fatherhood but, YoungBoy later disclosed, because he happened to be holding his son during its recording.) In Newark, he appeared transformed by his period of incarceration and house arrest—not so much reformed by these episodes as haunted by them. The primary stage decoration, apart from the coffin, involved a miniature house featuring a zig-zagging line circling it horizontally, enabling it to fracture like a massive egg, with YoungBoy confined within the shell. In this setting, even a straightforward boast regarding wielding a Beretta conveyed sorrow. “I simply drew my ’Retta and attempted to halt a guy / I merely exited my residence and nearly shot a guy,” YoungBoy rapped, in a melancholic track titled “House Arrest Tingz,” possibly unfolding from the vantage point of a person whose antisocial tendencies are amplified by his isolated condition.

Something regarding this tour has captured the public’s attention—in recent months, YoungBoy has been more conspicuous than ever. The streamer Kai Cenat documented himself attending a YoungBoy show in Los Angeles and shedding tears during “Heart & Soul,” a form of self-admiration where YoungBoy refers to himself by his given name: “Kentrell, you must mature, you’ve fathered all these children.” (For YoungBoy, as for many hip-hop figures, the intense tracks amplify the impact of the gentler ones.) Football teams have been playing “Shot Callin,” the breakthrough track from “MASA,” to mark triumphs. And, during a recent Apple Music interview, Keon Coleman, a twenty-two-year-old wide receiver for the Buffalo Bills, proposed that YoungBoy should perform a Super Bowl halftime show. The interviewer, veteran hip-hop radio personality Ebro Darden, fifty, expressed disbelief. “That individual can’t ascend that stage and produce a proper performance that will amuse anyone,” he stated, assuming the role of hip-hop elder statesman. “He won’t practice!”

Coleman was confident it wouldn’t matter. “He requires no supporting singers, no dancers, no camaraderie,” Coleman stated. “He stands alone.”

Indeed, YoungBoy did bring roughly a half-dozen dancers, all female, to his concert in Newark, yet they appeared hilariously incongruous alongside the star, who barely moved and rarely smiled, deferring to his d.j. to issue the urgings that hip-hop audiences have come to anticipate. (“Jersey, I require you to generate some damn sound within this venue once!”) Upon its conclusion, after more than two hours, YoungBoy simply remarked, quietly, “I thank you for coming out to watch me this evening.” He has pledged to issue at least one more album this year, which numerous individuals will undoubtedly overlook, despite YoungBoy’s recent moment of visibility, but which his supporters will certainly relish. There exists something miraculous about his capacity to make rap lyrics feel like sacred testament. And there is something miraculous, too, about the manner in which hip-hop, following approximately a half-century of history and hits, has sustained its knack for accomplishing precisely this: discover a troubled yet fascinating youth from Baton Rouge, position him on stage—“alone,” or nearly—and enable millions to rap along. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com