Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Wayne Thiebaud (1920-2021), who is best known for his celebration of the American vernacular, was thrilled when I first contacted him for a New Yorker cover, back in 2002. “When he’d get a call from you,” his son, Matt Bult, told me on the phone recently, “he would stop everything and go to his desk. It brought out the old design person in him. He would mock up the lettering and the color strip down the side—he loved doing those covers.”

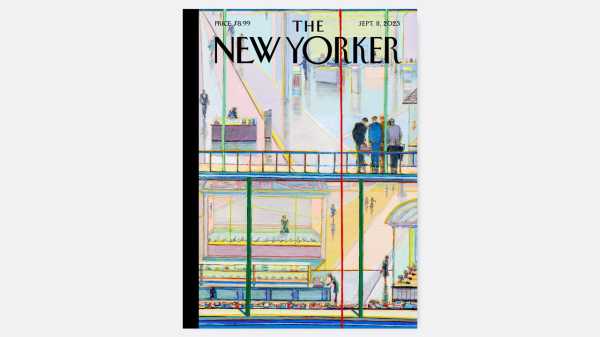

Thiebaud’s creamy paintings, not only of cakes and pies and still-lifes for the consumer age but also of vertiginous city views, sunny beaches, and densely folded landscapes, made him a quintessential painter of the American art scene during the seventy years of his career. Bult, who runs the Wayne Thiebaud Foundation with his wife, Maria Bult, proposed this late work, “Office and Shopping Mall, 2005-2021,” for the cover of the September 11, 2023, issue. I talked to Bult about Thiebaud’s irrepressible urge to paint and to refine his paintings, his facetious use of disguises, and his last days.

You’re a painter yourself, and your brother, Paul, who passed away from cancer, in 2010, was an art dealer. Does an artistic inclination run in the family?

Wayne has been my dad since I was three (my mom was his second wife), but, yes, I always knew I was going to paint. When I went to art school, at U.C. Davis, I studied art history. My brother and I took a few of Wayne’s theory-criticism classes on painting and sculpture. We both sat in front. Most people didn’t know who we were, so that was fun. And now my son Nick just graduated from U.C. Berkeley in art history, so, yes, it really does run in the family.

This painting is dated from 2005 to 2021, which was the last year of your father’s life. Did he often work that long on a painting?

Yes, in 2021, for the first half of the year—he was a hundred years old—he was still able to go to his studio every day. He was working on this painting and on a series of clown paintings. He often felt he should develop something a bit more and wanted to rework older paintings. He was unstoppable. Sometimes he would come over to our foundation, see a painting of his that was already framed and hanging on the wall, and he would say, “Take this out of the frame for me and bring it over.” And I’d bring over a painting, or a matted print, or a drawing, and he’d add to it with colored pastels.

This devotion to his work is quite wonderful!

Well, it is, unless you are the art archivist, and the work has already been photographed, included in catalogues, and is scheduled to go to a show—because then we have to start over and rephotograph it. We have a whole showroom here at the foundation, and I caught him in there with the lid of a can of tennis balls full of paint in one hand, putting blue shadows on some of the painted desserts! I said, “You can’t be doing this”—but he was truly unstoppable. And they were his paintings. He even worked on them while they were hanging in an exhibit. Once, at the Crocker Art Museum, he took a painting down right in front of the curator. He laid it on the ground, pulled a little can out of his pocket, and started varnishing it.

Thiebaud did a few paintings of shopping malls and office buildings. What was so attractive to him about those environments?

He liked painting cityscapes, including people in offices staring out of the windows—I think that’s where it started. Malls are an extension of his interest in how we display things and put them in boxes and cases. He was fascinated by people moving around in these spaces.

He told me that he seldom painted on location, but did he hang out in malls to sketch or watch people?

He did a lot of sketches, but that was while watching TV at night. That’s when he’d sit there with sketchbooks and do studies of people. Once, a while back, he was with my mom, sketching in a bank. Security came over and asked, “What do you think you’re doing?” “I’m just sketching,” he said. They told him to stop—he could have been checking out security cameras or the guards’ changing times. That impulse got squelched there and then.

He could have been a thief or a detective.

Absolutely. When he went out to New York galleries, he’d wear a long trench coat à la Humphrey Bogart, and pull a stocking cap over the rim of his glasses. That was his disguise. The gallery people wouldn’t recognize him, but he’d sign the guestbook, and later on they’d realize, Wayne Thiebaud was here?

Your dad passed away on Christmas Day a year and a half ago, at the age of a hundred and one. Do you feel he was ready?

Earlier that year, he had to stop going to the studio, and stop playing tennis, both of which he had done steadfastly until then. He always said, “You’ve got to keep moving—and once you can’t, it’s going to go fast.” That’s exactly what happened. Two weeks before his death he asked me, “What will happen if I stop eating and drinking?” And I said, “Well, you will die.” And then he would not take anything else, and he slowly went out. We spent Christmas Eve with him and family, our boys and other grandchildren, and on Christmas Day, we were planning a big dinner. We live about two blocks away, so we were close. That evening, my wife, Maria, went home to cook. We got a call from the caregiver, and I went over, and she told me he had just taken his last breath. Wayne was determined to go his own way, in his bedroom, in his own house. He had a long run, and he always said he felt lucky and fortunate to be able to concentrate on his teaching, on his art work, and on the people he loved.

See below for more covers by Wayne Thiebaud:

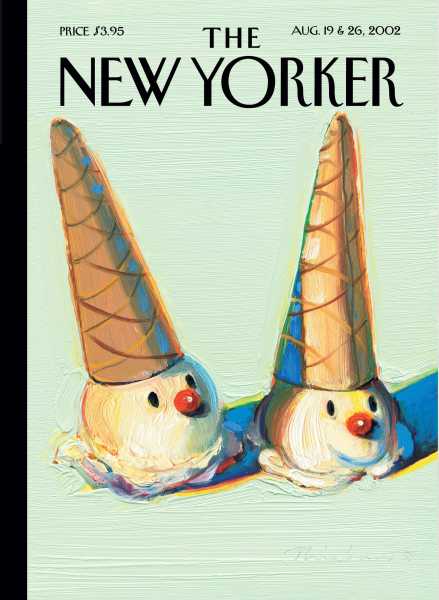

“Jolly Cones”

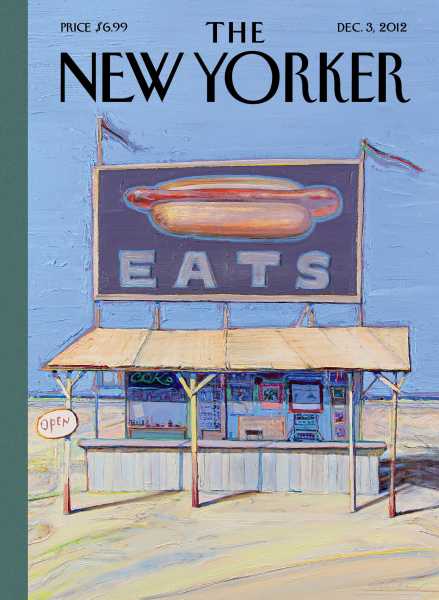

“Hot Dog Stand”

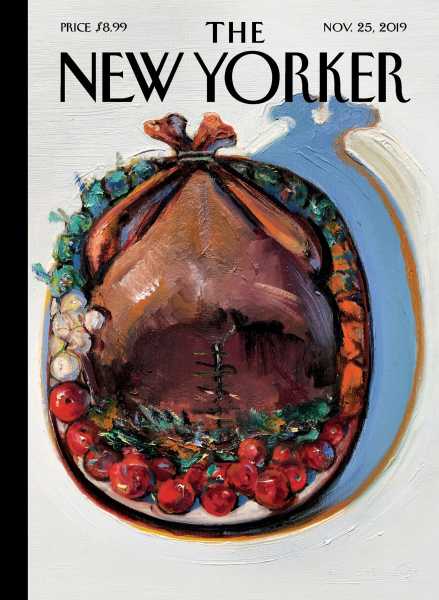

“Stuffed”

Find covers, cartoons, and more at the Condé Nast Store.

Sourse: newyorker.com