Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

A falling off can indicate decline or diminishment, often gradual—the petering out of a business, for instance, or the decay of a once marvellous building. Or it can refer to something abrupt, absolute. The ancient Greeks perceived such a falling off as the literal end of the world, the point beyond which humans could not go; they imagined the land mass as a vast island or disk surrounded by a boundless ocean, what the poet Pindar called “the untrodden sea.” Both senses haunt Barbara Mensch’s photographic history of lower Manhattan, in particular the Fulton Fish Market, which, for a time, was an island unto itself.

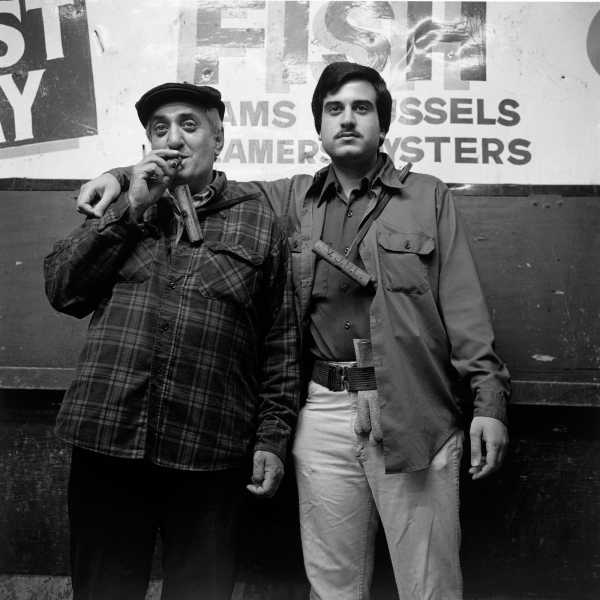

Fulton Fish Market, 1982.

South Street, 1982.

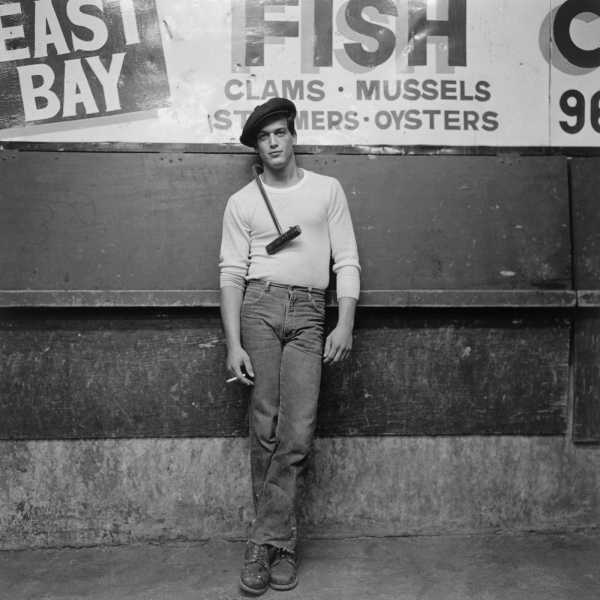

Fulton Fish Market, 1982.

The destruction of Beekman Dock, 1983.

Mensch’s new book of black-and-white photographs, “A Falling-Off Place: The Transformation of Lower Manhattan,” documents the market and the southern tip of Manhattan across more than forty years, beginning in the early nineteen-eighties. Around the same time, Mensch moved into a fifth-floor loft in a nineteenth-century maritime warehouse on Water Street, where she still lives and works. Its windows on one side look out on the anchorage of the Brooklyn Bridge, just across the street. The enclave of her seaport neighborhood is pressed up against the East River and was once studded with piers and docks that served as landing places for the myriad fishing vessels that brought in thousands of pounds of seafood every day.

Mensch was drawn to the nighttime theatre of the market—the rows of fluorescent lights and fish bins on the selling floor, the busy camaraderie of the workers, and what she called the “Rube Goldberg contraption” in the icehouse, which broke up huge pieces of ice into fine chips that were delivered via chute to men with barrows outside. She knew the city planned to demolish certain structures around the fish market, and she felt an urgency to document everything before it no longer existed. She tried visiting a few times at night but was chased off, not because she was a woman but because the area was being scrutinized in a way it hadn’t been before. The Mob had been part of the fabric of the fish market for decades, and in the early nineteen-eighties federal investigators were pursuing a broad investigation into the market’s criminal ties. When Rudy Giuliani took over as U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, in 1983, he made organized crime a top priority. Paranoia was rife down on South Street, and strangers like Mensch were viewed with suspicion.

In front of the New Market Building, 1982.

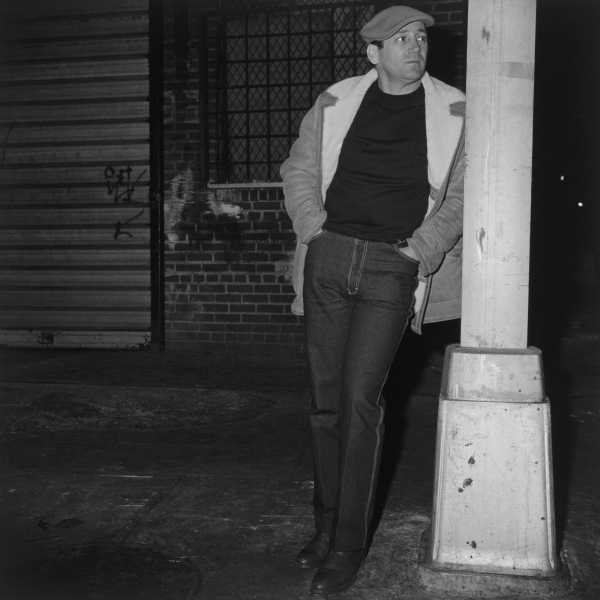

Mikey the Watchman, 1981.

A retired Fulton Fish Market worker, 1982.

The Paris Bar, on South Street, across from the Fulton Fish Market, 1980.

She spent some two years making inroads with the market workers, visiting them as they worked at night, at first, hiding her Rolleiflex camera inside her jacket. In order to show the bosses the kind of project she hoped to do (and to convince them that she wasn’t a federal agent), she came armed with monographs by artists such as Darius Kinsey, who, with the help of his wife, produced photographs of the logging industry in the Pacific Northwest from the turn of the century until 1940. Kinsey made portraits of lumberjacks posing with crosscut saws and reclining in crevasses carved into the trunks of massive firs. He captured teams of oxen dragging logs along a skid road and a sweeping view of men dwarfed by a steam donkey that, in turn, looks inconsequential amid the soaring old-growth forest. Drawing inspiration from Kinsey, Mensch wanted to produce a visual essay of a place and its community across an extended period of time. Only by immersing herself in the activity of the waterfront could she begin to understand its depth.

Once she’d gained access, Mensch found herself talking to Damon Runyon types with names such as Mombo, Johnny Deadman, and Mikey the Watchman in joints like the Paris Bar, Dirty Ernie’s, and Sloppy Louie’s, the restaurant that Joseph Mitchell made famous in a 1952 Profile, in this magazine, of its proprietor. Mensch’s bewitching portraits of individual salesmen and unloaders are of a piece with Mitchell’s sympathetic character studies—tonal representations of personalities that are inseparable from their environs.

Mensch was in the streets until seven in the morning, when white-collar workers headed to Lower Manhattan’s financial institutions. A photograph from 1983 shows the cultural clash that occurred in these early hours, as the rest of the city came alive. The nineteenth century is just visible in the background, walled off by plywood fencing: the masts of the South Street Seaport Museum’s tall ships rise like barren pines, and iron-and-brick waterfront warehouses appear crisp and silvery in the bright early light. In the foreground, a clean-cut man with a briefcase strides across the potholed asphalt. The shutter can’t keep up with his brisk motion, and his form blurs at the edges.

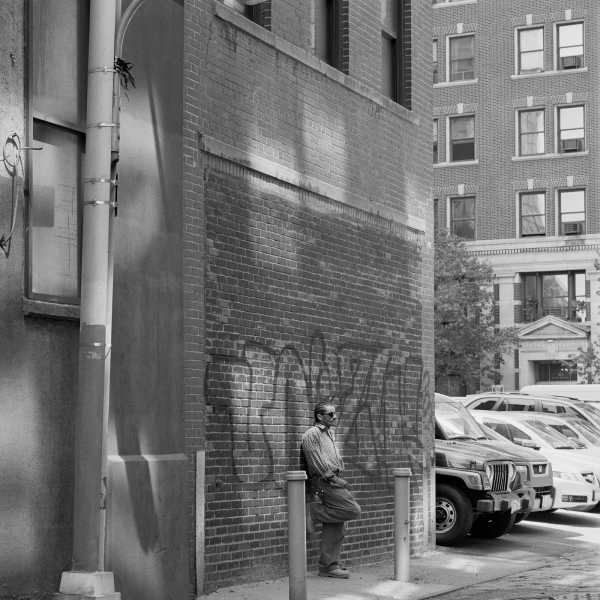

Near Pearl Street, 1983.

Cobblestones from the nineteenth century, appropriated for a revitalization plan, 1983.

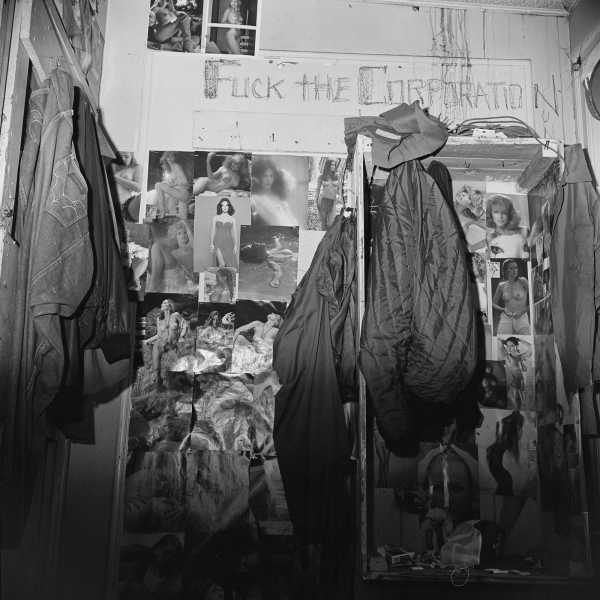

Upstairs locker room above Carmine’s Bar & Grill, 1982.

Schermerhorn Row, 1999.

With the Brooklyn Bridge acting as a bulwark, this slice of New York was tucked away from the rest of the city. But modernity couldn’t be kept at bay. Mensch’s photographs of men weighing fish, hauling bags of mussels, and pulling wooden barrows filled with ice are interspersed with shots of the destruction of Beekman Dock and of mounds of century-old cobblestones ripped up to be repurposed in so-called revitalization plans. This era in the book is punctuated by a grim sequence of photographs. In 1982, Mensch captured a handwritten sign in the locker room over Carmine’s Bar & Grill, on Beekman Street, that reads “FUCK THE CORPORATION.” “That’s the story,” she told me. “They knew what was coming.” On the following spread, two crowded images from 1985 mark the opening of a commercial complex on the new Pier 17—throngs of shoppers and sightseers eager to visit the seaport mall.

Mensch catalogues the spasmodic conversion of lower Manhattan during the next decade. An ornamented Victorian clock gathers dust on Duane Street, and an obliterating fog envelops a security guard along Schermerhorn Row. Floods, demolition, and arson clear the way for glass-and-concrete condominiums and chauffeured limousines. The ultimate destruction comes on September 11, 2001, an event that Mensch documented as it was happening. Her captions throughout the book give only minimal information, but occasionally her grief becomes visible, as when she writes, of the intersection of Maiden Lane and Fletcher Alley, in 2003, “Centuries ago, a babbling brook ran through here; today this location is the site of a new luxury tower.”

Maiden Lane and Fletcher Alley, 2003.

In 2005, she photographed the market’s last hours at its two-century-old lower-Manhattan location. In one photograph, a thin coating of snow and a handful of lights in the deserted market building brighten the center of the image, a beacon in the November night. In the background, the dark form of the Brooklyn Bridge disappears behind the market, but the necklace lights along the bridge’s cables appear to fasten onto the building’s second story, a link across the few blocks between them. The photograph becomes an intimate portrait of two landmarks that grew up in the city together, intertwined.

One of Mensch’s photographs from 2020, when the city tore down both the Tin Building and the New Market Building, illustrates the cross-hatching of historical periods characteristic of New York. The rigging used to demolish the New Market Building presses up against the picture plane so that it appears magnified, a monumental array of intersecting lines and forms resembling a David Smith sculpture. Behind it, the radiating suspension cables of the Brooklyn Bridge are a delicate web hovering roof-like over low-lying buildings and a sloping stretch of the F.D.R. Farther in the distance, competing in scale with the bridge’s west tower, is a rippling glass skyscraper, derisively called the cheese grater, which opened in 2019.

What is lost and what is gained in such transformations? Mensch doesn’t address the question directly, but it’s not hard to see what sort of answer she might give. The book’s final photographs, from the past couple of years, depict several new high-rises that seem indifferent to the people below—people perhaps unmoored by a city that no longer affords the familiarity of distinct neighborhoods. Mensch includes a vista of the cheese grater, here cutting a lonely path into the sky far above more modest buildings, jutting upward from the city like the handle of a sledgehammer.

The east side of lower Manhattan, 2020.

Sourse: newyorker.com