Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

There’s so much going on in “In the Medium of Life: The Drawings of Beauford Delaney” (at the Drawing Center through September 14th) that you may leave the show wishing there’d been less. Less of Delaney’s middling work, less archival material, and less of a push to establish him as a significant American artist. Although he was significant—unique to his time and place—he has rarely been presented in a way that encourages a deeper understanding of the art itself. Curators and writers tend to sentimentalize his story, foregrounding hardscrabble beginnings in turn-of-the-twentieth-century Tennessee and his success in becoming a friend to such cultural stars as Georgia O’Keeffe and James Baldwin, and fail to discern, with a critical eye, which pieces shine and which should be forgotten.

In “In the Medium of Life,” Rebecca DiGiovanna and Laura Hoptman, the assistant curator and the executive director of the Drawing Center, respectively, do make a firm critical case for Delaney, but they are hobbled by the fact that the Drawing Center shows primarily drawings and can’t fully explore the connections between these mostly lesser works and Delaney’s stronger paintings. To compensate, they show more drawings than they should and more than they have room for—the show feels crammed. Stephen Wicks, in his 2020 exhibition at the Knoxville Museum of Art, “Beauford Delaney and James Baldwin: Through the Unusual Door,” understood that it is necessary to have a lot of air around Delaney’s art. His surfaces are densely textured and vibrant. If the pieces are hung too close together, your eyes tire quickly, and you can feel as if Delaney’s world is closing in on you, while his intensity is shutting you out. Of course, being shut out is the last thing that DiGiovanna and Hoptman want you to feel, and you’d be hard pressed not to recognize the good intentions in their invitation to feast on the seventy-six drawings and five paintings they’ve assembled, along with some fascinating ephemera—newspaper clippings, diary entries. Hoptman’s aim, which she makes clear in the catalogue, is to release Delaney from his biography, from his fame by association, and to focus on how he became freer and freer as an artist as he became more and more himself.

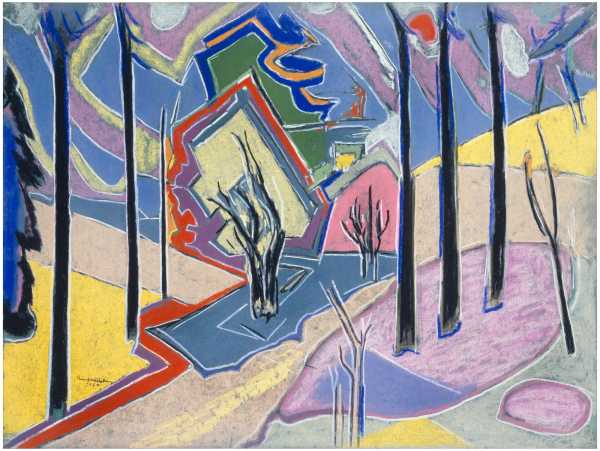

“Central Park,” 1950.Artwork by Beauford Delaney / © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Delaney’s style or, more accurately, styles, developed in the course of a long apprenticeship that can read like a novelization of the desperate life of an artist—van Gogh as reimagined by Irving Stone. Like the real van Gogh, Delaney suffered from mental illness, and sometimes heard voices telling him that he was inferior because he was Black or slurring him for being gay. Delaney’s skills as a draftsman were discovered when, still in his mid-teens, in Knoxville—where his mother took in laundry and cleaned houses to support the family—he was employed for a time at a shoe-shine and leather joint. One day, he accidentally left a sketchbook at work. Impressed by what he saw, Delaney’s boss introduced the boy to a local artist, an upper-class white painter named Lloyd Branson, who offered to give him art lessons in exchange for help in his studio. Eventually, Branson encouraged Delaney to leave Tennessee and head north. In 1923, the then twenty-two-year-old burgeoning artist landed in Boston, where he took classes at the Copley Society and the South Boston School of Art, while supporting himself as a janitor for the Western Union Company. He also established contact with some members of the city’s Black bourgeoisie, thanks to letters of introduction from his pastor in Knoxville and others.

In Boston and, later, in New York—where he moved in 1929, living first in Harlem, and eventually settling downtown, in underdeveloped SoHo—Delaney didn’t so much develop a style as try to understand how to make a picture. The work from those years has no inner light. One wonders if he was avoiding making art that required him to go deep into his mind, a frightening and bewildering terrain. “Nobody knows my face,” he wrote in a journal entry in this period. Loneliness was his constant companion. As David Leeming tells us, in his essential 1998 biography, “Amazing Grace: A Life of Beauford Delaney” (I wrote an introduction to the book when it was reissued, last year), some doors were shut to Delaney in New York, because of his skin color; certain art schools didn’t admit Blacks. Despite the obstacles, though, Delaney could hustle, and one of his hustles was to find prominent people of color who could act as protectors. His sweetness, his Southern manners, and his growing talent were on his side.

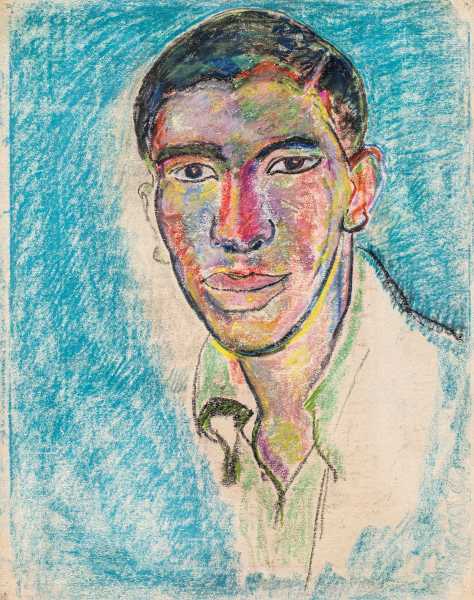

In early 1930, a friend encouraged him to contact a woman who worked at the Whitney Studio galleries, on West Eighth Street, and he was soon offered a spot in a show devoted to “Sunday painters,” or “naïve” artists. The three oil paintings and nine pastels by Delaney that were included garnered favorable press, but that wasn’t enough to live on. He took a position at the Whitney as a caretaker and then as a telephone operator and occasional doorman and guard. He also picked up work as an art instructor whenever he could (and it was not uncommon for him to give his meagre earnings away to itinerant people he met and sometimes invited into his home). Delaney’s work from the thirties in the Drawing Center show is still representational and straightforward, almost always depicting a male figure in profile, or three-quarter profile. He handles pastels well in “Untitled (Portrait of a Man)” (1930), a drawing of a young white man, but the portrait is not particularly successful, because Delaney is too distant and perhaps too admiring of the man’s beauty to make any inquiries into his being. Still, Delaney’s use of color in the piece—the man wears a forest-green coat that draws out the dark-green background—hints at his growing fascination with shade, shape, and light.

While Delaney’s eyes were open to modernism in these years—he was friends with both Alfred Stieglitz and Georgia O’Keeffe—I get the sense that for many years he was trying to figure out how to fit into modernism. Feeling odd in his mind and in the world he inhabited—drinking helped silence the voices that called him “nigger,” but there was no protection against the men who took advantage of his softness and his queerness, and beat him up—he could not bring himself to expose anything on canvas when all he knew was how to hide. That’s the tension in his best work, and sometimes he overcame it, with a sense of release.

Untitled, c. 1940.Art work by Beauford Delaney / © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

I don’t know how much Delaney looked at the Fauvists, but I feel early-twentieth-century Matisse and André Derain in his breakthrough work of the forties, when he began to produce the pieces that stand out at the Drawing Center, including “Untitled” (c. 1940). It’s another pastel-on-paper portrait of a man, but Delaney is more relaxed, less of a perfectionist here, and the sensuality of the young man’s full lips and inquiring eyes hints at an exchange of sorts. It reminded me of “The Picnic” (1940), an astonishing painting, not at the Drawing Center, that shows Delaney becoming more joyful and committed to color as a realm—a mystical domain rooted in the real. “The Picnic” depicts what looks to be a family, or a family and their neighbors, sitting and reclining on a knoll. It’s a beautiful spring or summer day; above or near the figures, we see clouds—swipes of delicately laid out white paint in the blue sky. Light fills this private world of air and bending trees, illuminating the figures, whose skin is various shades of brown. The four women we can see clearly—the two figures lying in the grass to the right are harder to make out—are rendered in all their matriarchal fullness, their solid bodies clothed in yellow and pink. The picture evokes Sunday-afternoon contentment, when nature and faith and the body converge to create a moment of true grace.

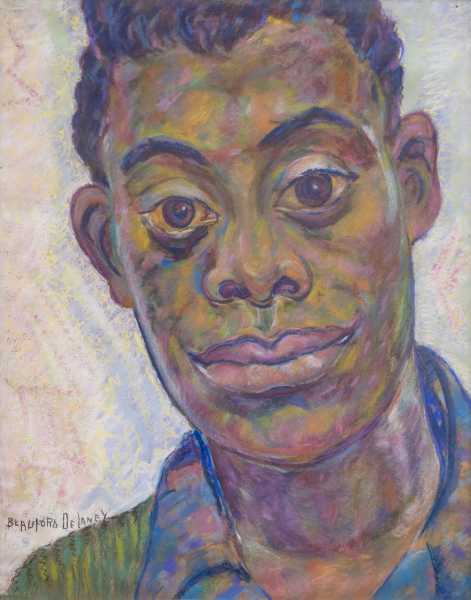

In a wildly romantic 1945 essay titled “The Amazing and Invariable Beauford DeLaney,” Henry Miller, a longtime friend, refers to the artist’s canvases as speaking of “darkest Africa,” but Delaney himself, who wanted to be known as an artist, not a Black artist, built his greatest work around the remembered intimacy of his youth in Tennessee. That intimacy involved both facing and turning away from his desire. That’s what makes the painting “Dark Rapture” (1941)—which isn’t in the Drawing Center show, though it is on view in a photograph of Delaney in the vitrine—so significant. In it, Delaney looks both back at the person he may have longed to be, and directly at the person who sits, unafraid, before him. In the image, a nude male figure is seated, with one leg tucked under the other, in a Fauvist wild. Pinks and blues and patches of red stand out against the sitter’s brown skin, his strong upper arms. The sitter is James Baldwin. Delaney and Baldwin’s almost forty-year friendship began in 1940, when Baldwin was fifteen and Delaney was in his late thirties. Each found in the other something that may have seemed impossible to both beforehand: a Black gay artist. It has been said that Baldwin sat for Delaney the day they met. Whenever it was, stripping down was one way for the would-be writer to show how much he trusted his new mentor. There’s a 1945 pastel of Baldwin at the Drawing Center: he looks uncharacteristically daffy in it, and it doesn’t tell you much beyond Delaney’s affection for his friend, but it’s fun to look at all the beautiful reds and browns that make up the young writer’s face and his famously headlight-wide, bright eyes—which Delaney helped open.

“James Baldwin,” 1945.Art work by Beauford Delaney / Photograph of art work by Ben Conant / © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

“Many years ago, in poverty and uncertainty, Beauford and I would walk together through the streets of New York City,” Baldwin writes, in a 1964 catalogue essay celebrating his friend. He goes on:

He was then . . . working all the time, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say that he was seeing all the time; and the reality of his seeing caused me to begin to see. . . . What I saw, first of all, was a brown leaf on black asphalt, oil moving like mercury in the black water of the gutter, grass pushing itself up through a crevice in the sidewalk. And because I was seeing it with Beauford, because Beauford caused me to see it, the very colors underwent a most disturbing and salutary change. The brown leaf on the black asphalt, for example—what colors were these, really? To stare at the leaf long enough, to try and apprehend the leaf, was to discover many colors in it; and though black had been described to me as the absence of light, it became very clear to me that if this were true, we would never have been able to see the color, black: the light is trapped in it and struggles upward, rather like that grass pushing upward through the cement.

One could read the above as a description of Baldwin and Delaney, too, pushing up through the cement of New York, their light evident to each other, but not to those who thought of blackness as having no light at all. In 1948, Baldwin left New York for Paris, and five years later Delaney followed.

There was something liberating about the journey, turning a new page, and you can feel that energy in the art that Delaney produced after he arrived in France. A real standout among the works is “Chartres” (1954). Measuring thirty by twenty-one and five-eighths inches, this oil-on-paperboard is not a literal rendering of the Chartres Cathedral’s windows but a fantastical representation of how the soul is affected by the awe-inspiring building and what it houses: faith. To stand near Chartres, let alone in it, is to be no longer grass pushing upward through the cement but a human being made small by the enormity of creation. The four oval shapes at the center of the picture are surrounded by flecks of paint that feel like pure energy circling one’s thoughts. In his notes from that period, Delaney wrote, “Keep the faith and trust so far as possible. Love humility and don’t mind the insinuations that cause sorrow . . . and loneliness and limitations. We learn self-reliance and to hear the voice of God, too. . . . Learning to love is learning to suffer deeply and with quietness.” Sometimes faith is all we have, and making anything—a painting, a story—is like catching it in a bottle and then throwing it out to sea.

“Chartres,” 1954.

Art work by Beauford Delaney / © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY

Delaney moved to Clamart, a southwestern suburb of Paris, in 1955, and began to produce a series of light-filled gouache-on-paper works. Baldwin, in his 1964 essay, describes the light in Delaney’s apartment there. The space, he noted, “looked out on a garden; or, rather, it would have looked out on a garden if it had not been for the leaves and branches of a large tree which pressed directly against the window. Everything one saw from this window, then, was filtered through these leaves. And this window was a kind of universe, moaning and wailing when it rained, black and bitter when it thundered, hesitant and delicate with the first light of the morning, and as blue as the blues when the last light of the sun departed. Well, that life, that light, that miracle, are what I began to see in Beauford’s paintings.” That window was Delaney’s Chartres, lit from within and without by the artist’s faith. There are several big examples of the Clamart work at the Drawing Center, and it’s hard to get a fix on the quality because they crowd one another out a bit. In any case, the light does come through, and in “Untitled (Clamart),” from 1959, Delaney offers a marvellous wilderness of browns and reds—autumnal colors that connote the crispness of fall, when foliage is struggling not to retreat and die.

Untitled (Clamart), 1959.Art work by Beauford Delaney / © Estate of Beauford Delaney, by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator, Courtesy Knoxville Museum of Art

I couldn’t help wondering, though, why Delaney’s portrait “Ahmed Bioud” (1961) was essential to the story of the Clamart light. One could make a case for its being a portrait of a man approaching Delaney through light, a ghostly man who is out of reach—but didn’t Delaney suffer the effects of that dream of unattainable love his entire life? By 1970, he was drawing his face—the face he claimed nobody knew—as a kind of cartoon. His line drawing “Self Portrait” (c. 1970) is not a work of art; it’s a curio by a man who was losing what was left of his mind. (A more profound evocation of the way artists show hope even as they are suffering is the minimal “Untitled (Red Bar),” from 1962—an unevenly rendered wide red line set against a green background, like a film leader running through someone’s thoughts.) Including this “Self Portrait” in a show devoted to an artist who suffered from schizophrenia drives a kind of wedge between Delaney the Artist and Delaney the Example. Look at what he suffered in order to become a self: poverty, racism, homophobia. But these are not the medals we should pin on Delaney’s artist’s smock. If we reduce him to that, he becomes a cause, just like all the other broken men of color who worked and died, including the composer Julius Eastman, and the writers Don Belton and Gary Fisher and James Baldwin himself. In the end, the voices that filled Delaney’s head drowned the light in his eyes, but no one could take the light from his paintings. What “In the Medium of Life” makes clear is that his drawings should be viewed in support of those paintings, rather than on their own. Separating the two turns Delaney into a spiritual and artistic orphan of sorts, despite all that he achieved and the home that he built for himself, painting by painting, in the free verdant air of his imagination. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com