Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In 1954, the Cuban ethnographer Lydia Cabrera published “El Monte,” a book that committed to paper the hitherto oral history of major Afro-Cuban religious traditions. Its title, which translates roughly to “The Wilderness,” refers not only to nature but to the separate, sacred space where, for those who practice Palo Monte and Lucumí—better known as Santería—spirits and deities reside. For decades, the book has informed the art of Cuban nationals and the Cuban diaspora. Among its readers was the artist Ana Mendieta, who was sent to the United States by her parents as a child, and for whom “El Monte” served as a lifeline to a homeland that haunted her work. Later, the Cuban collagrapher Belkis Ayón drew from Cabrera’s research to create the characters that populate her strange œuvre: one-dimensional, monochrome silhouettes, their only facial features a pair of stark, piercing eyes.

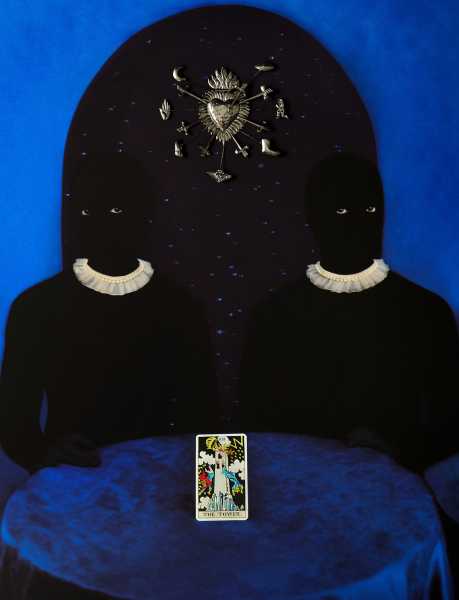

“El Monte (Ibejí),” 2024.

“Ophelia,” 2025.

It was Ayón’s work that brought the photographer Erick Jiménez to “El Monte.” At least, that’s how he remembers it; his artistic partner and twin brother, Elliot, recalls them both reading it sooner, in their twenties. (They’re now thirty-six.) Although they were born in Miami shortly after their parents arrived in the U.S. from Cuba, they described early childhoods nearly untouched by American culture, with the family television always tuned to Spanish-language news and telenovelas. “We weren’t fluent in English until maybe age nine,” Erick Jiménez told me. Still, when he and his brother revisited “El Monte” upon its initial publication in English, two years ago, they engaged with it through the lens of first-generation Americans. Around that time, they began working on their latest photo series, which takes the name of Cabrera’s seminal text, and is the focus of their first solo museum exhibition, at the Pérez Art Museum Miami, which opened this week, and runs until March 22, 2026.

“Who Is the Ram and Who Is the Knife?,” 2025

“The Tower,” 2025.

“Heavenly Twins,” 2024.

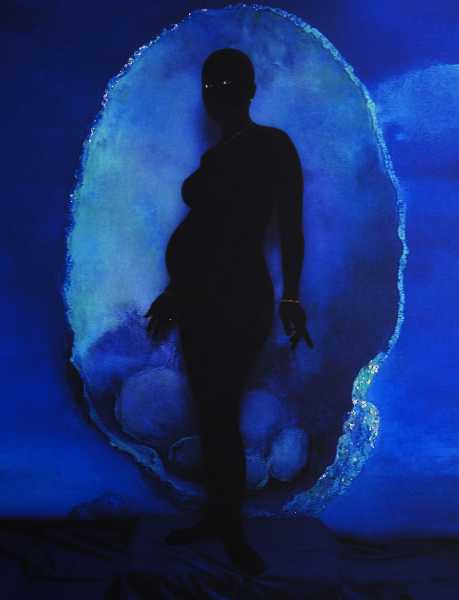

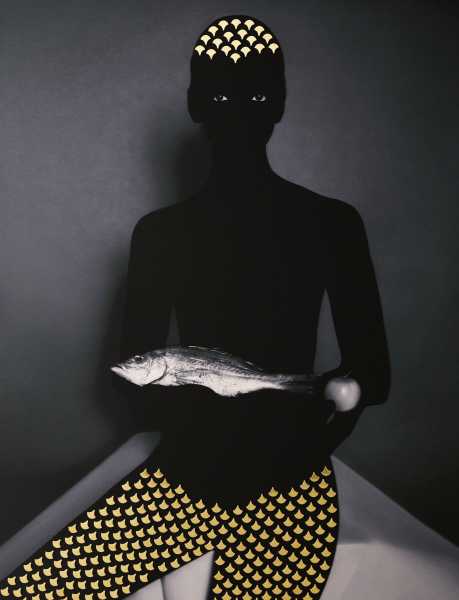

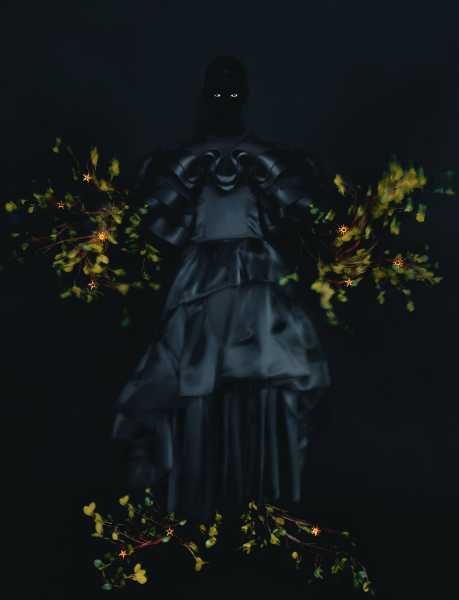

In this “El Monte,” the science of ethnography is traded for something less rigid, something more whimsical and unconstrained. Whereas Cabrera sought to present a faithful documentation of the occult, the Jiménezes build a dizzying world of multiple dualities, in which photographs appear to be paintings, Afro-Cuban and Greco-Roman mythologies mingle freely, and the aesthetics of Western art movements surround what the twins call “shadow figures”—models distilled into blacked-out, bright-eyed presences, redolent of Ayón’s visual universe.

“The Rebirth of Venus,” 2025.

“Criatura del Jardín” (Garden Creature), 2025.

“People are familiar with these European mythologies or famous art historical figures like Monet or Michelangelo,” Elliot Jiménez said. The series, he explained, is an attempt at “reinterpreting more iconic works in the context of Cuban culture and spirituality—the things we grew up with and that relate to us.” In one shot, Venus is reborn, dark and pregnant against a background of blurred blue. Sikán, a female figure from the lore of an all-male, Afro-Cuban secret society called the Abakuá, is portrayed holding the fish that sealed her fate. (The photo is dedicated to Ayón, who studied the religious order and eventually adopted Sikán as a kind of alter ego.) The Jiménezes’ version of the wilderness is a space in which dominant symbols and narratives undergo a process of transformation, even subjugation. Draped in lush fabrics or donning Elizabethan ruffs, the shadow figures command each frame they occupy.

“La mano y el secreto” (The Hand and the Secret), 2025.

“Sikán (After Belkis Ayón),” 2025.

“Árbol Dios (Ceiba)” (Tree God [Ceiba]), 2025.

“Daphne, sombra y monte” (Daphne, Shadow, and Forest), 2025.

First-generation American artists who traffic in nostalgia for places that they’ve mostly observed from a distance risk misinterpreting them—even Mendieta, at one time hailed as an insider to the mystical realm, has been criticized for not having sufficient understanding of the Afro-Cuban religions that she referenced in her art. But the Jiménezes’ work does not carry the pretense of purity. It is playful, and when their photographs are at their most triumphant—and also, perhaps, their most American—they embrace surreality, contradiction, artifice, and appropriation. In an image titled “Imperialista,” a shadow figure poses regally underneath a bicorne hat suited to a Napoleonic officer. Staring into that gaze, I almost expected it to wink at me.

“Imperialista” (Imperialist), 2025.

Sourse: newyorker.com