Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

How do you reacquaint yourself with the country you’re from? Until he was twelve, the photographer Adam Ferguson lived in Dubbo, Australia, a small city about five hours’ drive from Sydney. His grandparents lived an hour away, in the small farming community of Yeoval. “My nan was from the land,” he told me recently. Then Ferguson’s family moved to the coast and, after college, he went abroad. For sixteen years, he was based in New York but travelled widely to cover international conflicts—in Afghanistan, for this magazine; Nigeria, for the Times; and elsewhere. Eventually, he told me, he found himself feeling homesick and traumatized, but also confused. “I’d spent so long working through translators,” he said. “I wanted to tell a story about my own country, my own people—something that I know intimately.”

Kent Morris and Sam Cormack, their children, and Kent’s mother Lainie, in Gunggari Country, Kandimulla Property, south of Mitchell, Queensland, 2018.

Sheep rot in a pit, in Weilwan Country, Epping Farm, Pilliga, New South Wales, 2018.

Fifth-generation farmer Jack Slack-Smith—photographed in Weilwan Country, Epping Farm, Pilliga, New South Wales, in 2018— sold five thousand acres to survive the drought.

A high-based thunderstorm moves across drought-affected land, in Kunja Country, Tuen, Queensland, 2018.

He started coming back to Australia for progressively longer stays, and went in search of the people a twelve-year-old might want to meet: the drover, the cattleman, the roo shooter. What he found were individuals who both did—and didn’t—fit the ideas he’d had about his home. Cattlewomen, for instance, and Swifties, and drunk lovers, and a drag artist playing Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, in a tribute show at a local pub. In late 2021, he moved back to his homeland for good—or, at least, for now. The photographs he has taken there in the past decade are collected in his first monograph, “Big Sky” (Gost).

Cousin-sisters Shauna and Bridget Perdjert, of Kardu Thithay Diminin Clan and Murrinhpatha language group, in Kardu Yek Diminin Country, Air Force Hill, Wadeye, Northern Territory, 2023.

Chairs secured from flooding, in Iningai Country, Lake Huffer Station, Queensland, 2017.

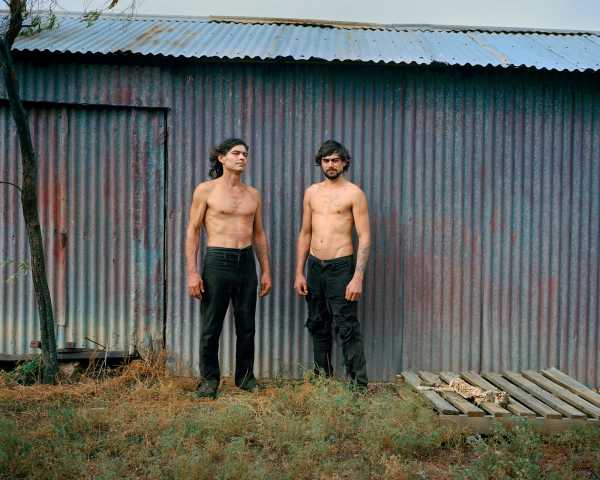

Contract shearers George Smith (left) and his son Conan Wakefield, in Iningai Country, Marchmont Station near Ilfracombe, Queensland, 2017.

Ferguson and I talked in my kitchen in the Bondi Beach area of Sydney, about as far from the country’s Red Centre as you can be. Almost all Australians live on the coast: the entire outback is home to less than five per cent of the population. Sitting at my dining table, framed by my IKEA bookshelves, and wearing elegant spectacles and a pristine khaki sweater, he looked a little New York. Then again, he’d eaten a meat pie for lunch, and he ribbed me for not knowing the Australian term for a spinning clothesline: Hills Hoist. (I grew up in South Africa.) The homegrown invention had come up because Ferguson had photographed Shelita Buffet in drag, in her garden, under a hoist whose pinky-orange and faded-blue pegs fasten several of the colors in the rest of the photo: bits of sky, plastic, and flowers.

Dwayne John, off-siding a commercial kangaroo shooter, in Adnyamathanha Country, Plumbago Station, South Australia, 2017.

“The country’s just a giant bloody cattle station or a mine,” Ferguson told me. “Cattle have totally transformed the landscape.” His photographs have their own powers of transformation. Towers of almonds, covered haphazardly with plastic sheeting and held down by car tires, become a misty valley; a rainbow ends not in a pot of gold but at an opal-mine junk yard. Kids at the top of the stairs on a playground slide call to mind brushtail possums caught in the beam of a flashlight. A man lies face down on his horse, and a hat has fallen to the ground—it is the horse, not the man, who seems likeliest to have lost it. In another portrait, Dwayne John, the wingman to a commercial kangaroo shooter, cradles a massive male big red; plum-colored blood coats its ear and snout. John, Ferguson told me, was partway through a night he would spend quietly and methodically shooting dozens of the creatures; enough, in the course of about two weeks, to fill a refrigerated semi-trailer with meat. The night ended with John and his boss, Tony, driving to a claypan, where they broke the animals’ joints, gutted them, and cut off their legs, tails, paws, and heads, leaving the limbs on the compacted, hard surface of the pan for feral cats and birds of prey.

Drag Queen Shelita Buffet, before a performance at the Palace Hotel, in Wilyakali Country, Broken Hill, New South Wales, 2017.

In the Northern Territory, Ferguson photographed modern Aboriginal country. He took several portraits of Bridget Perdjert, twenty-four, an initiated woman and the granddaughter of Margaret Perdjert, an influential elder in Kardu Yek Diminin Country. The photograph that appears in “Big Sky” is of Bridget and her cousin-sister Shauna sitting on a shady rock far above a wide plain. Shauna looks ahead; Bridget turns around and gives the camera a tough look. Both wear Taylor Swift T-shirts. They are earnest pop fans in a land of heavy-metal crews: the nearby township of Wadeye is known for its gangs, named for American bands—the Slayer mob, the Judas Priest boys.

Sam McMahon, a ringer with Brett Cattle Company, in Ngarinyman and Malngin Country, Waterloo Station, Northern Territory, 2023.

Isla Hughes, a governess from a remote cattle station, in Wongkumara Country, New South Wales, 2017.

After the Bachelor and Spinster Ball, in Wiradjuri Country, The Rock, New South Wales, 2019.

In Ngarinyman and Malngin Country, Ferguson asked a young ringer—a stockman or cattle hand—to kneel in front of a bougainvillea bush. “I wanted him to feel vulnerable and I wanted to position him next to something that was foreign,” Ferguson said. The man’s arms hang limply at his sides; he seems at a loss before the flowers’ pink abundance. Many of Ferguson’s photographs appear to be of the moment between someone making a decision and their next move, but the images also reveal a certain helplessness, as though the people in them have not reached this point entirely by choice. Climate change will do that to a person at the mercy of rain; as will the need for love.

A cultural burning near Wirrimanu/Balgo, Kukatja Country, Western Australia, 2023.

That moment is where Ferguson finds himself, too. Asked whether he plans to stay in Australia, he says he doesn’t know.

The Pintupi-Luritja Lutheran pastor Simon Dixon, in Ikuntji/Haast Bluff, Arrernte Country, Northern Territory, 2023.

Sourse: newyorker.com