Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Every year, the United States welcomes hundreds of thousands of new citizens in naturalization ceremonies that manage to be both banal and deeply moving. An official leads the room in the Pledge of Allegiance; citizens-to-be repeat the unwieldy phrases of the Oath of Allegiance, promising to “abjure all allegiance and fidelity to any foreign prince, potentate, state, or sovereignty” to which they have “heretofore been a subject or citizen.” Everyone claps and sings a patriotic song.

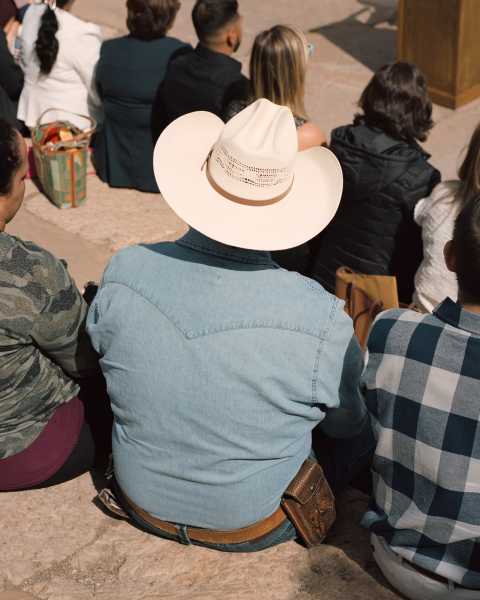

Officials at the ceremony in Grand Canyon National Park.

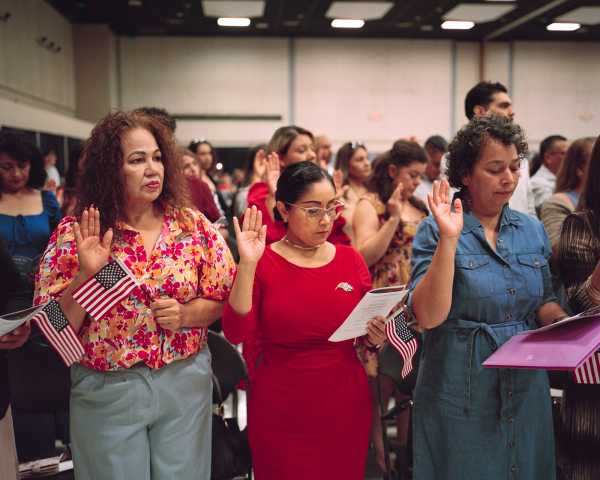

New citizens at the ceremony in Yuma.

The United States government hosts the ceremonies year-round, but there is an extra flurry of activity during Constitution Week, in late September; this year, more than seventeen thousand new citizens were naturalized that week in some four hundred ceremonies across the country. In a courtroom in Yuma, Arizona, about a dozen miles from the Mexican border, more than two hundred people watched screens displaying a montage of American scenes—Mount Rushmore, the Statue of Liberty, the New York skyline—set to a soundtrack of soaring string music. At an outdoor ceremony overlooking the rim of the Grand Canyon, thirty newly naturalized citizens snacked on slices of apple pie as a jazz band played patriotic standards.

Isabel Ferrales, who became a citizen in the Grand Canyon ceremony, has lived in the U.S. since the eighties.

New citizens wave flags at the ceremony in Yuma.

Manuel Chihuahua was naturalized at the Grand Canyon.

Three friends from the Marine Corps—Erick Sanchez Angel, Cristian Joya, and YenChen Lai—became citizens in the Yuma ceremony.

For many of the participants, the ceremonies were the culmination of years, or even decades, of forms, fees, interviews, and waiting. “For me, this was a twenty-five-year journey,” a woman from Turkey told me at the Grand Canyon. Her face was composed, but she kept wiping away tears. Near her was a cluster of men in work clothes. They had come to celebrate their colleague, a maintenance worker in the Grand Canyon National Park, who had grown up in Venezuela. “When I learned to read, the first thing I saw in a book was a picture of a Native American warrior looking at the Grand Canyon,” he said. “I said, ‘What is this warrior doing on another planet?’ Fifty years later, the Lord had a job for me right here in the Grand Canyon. And now I am part of the landscape, and I am a citizen of the United States.”

New citizens and their friends and families took part in the Grand Canyon ceremony.

Citizenship confers a host of benefits and privileges, many of which are invisible to those who were born into them. A single mother from Mexico who worked at a state prison outside Phoenix needed citizenship to be eligible for better-paying, less dangerous jobs at the federal level. Citizenship was a necessary precursor for security clearance, a young marine from Mexico told me. A couple from India described how difficult work trips could be for noncitizens—they had to start seeking visas months in advance, sometimes travelling as far as Los Angeles to obtain them. “Honestly, I’m most looking forward to the freedom—to not feeling like I have to look over my shoulder when I’m driving, or when I cross the border,” a soccer coach from Ghana told me.

Parikshith Kumar and his wife, Ambika Sharma, were naturalized at the Grand Canyon.

During his Presidency, Donald Trump imposed a myriad of immigration restrictions, which led to a large-scale reduction in legal immigration and slowed the process for those eligible for citizenship; office closures during the pandemic made the backlogs even worse. The Biden Administration reversed many of Trump’s policies: in the 2023 fiscal year, nearly nine hundred thousand people took the Oath of Allegiance to become new citizens, up from seven hundred thousand in 2017, and the share of the population who were born elsewhere was, at 14.3 per cent, higher than it had been in more than a century. (That figure still puts the U.S. below many European countries, in terms of the percentage of the population born abroad.) But persistent fearmongering over people entering the country, both legally and illegally, is taking a toll on the public support for immigration. For the first time in almost two decades, a Gallup poll found that a majority of Americans believe the country should welcome fewer immigrants—a marked shift from just a few years ago.

Keila Villanueva Ramírez (third from left) celebrates her new citizenship with her family in Yuma.

Isabel Ferrales, who came to the U.S. from Mexico as a teen-ager, in the eighties, told me that she was dismayed by the ways in which immigrants were demonized as criminals or held up as objects of pity. In social-media posts, people rarely distinguished between different kinds of migrants, she noted; viral videos showed masses of people travelling in caravans or rushing toward the border fence. “That’s what gets amplified, and it dehumanizes the struggle,” she said. Ferrales explained that her father, a mechanic who worked on agricultural equipment, had entered the country under a special program for agricultural workers: “I’m an example of how immigration reform does help families.” She currently works for the Navajo Nation, and she’s been describing the immigration process to her Native American co-workers. “They had no idea that it costs money to apply, that it takes time, that if you live in a rural area you have to travel to a city,” she said.

Roses at the Grand Canyon ceremony.

Yussif Bello Alhassan celebrates his new citizenship in Yuma.

Tetiana Zamoroz was naturalized at the Grand Canyon.

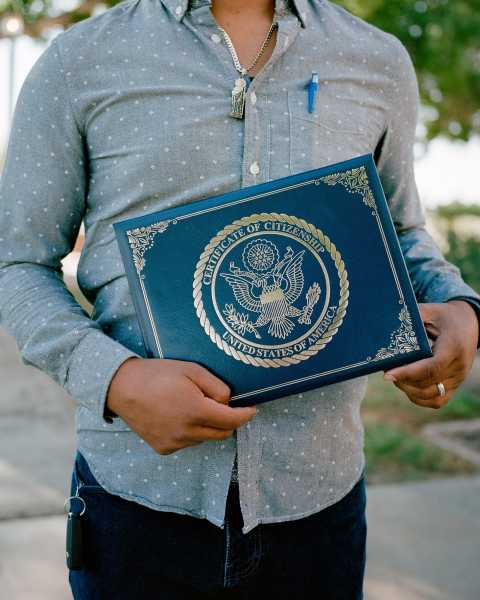

Ricardo Arana holds his certificate of citizenship in Yuma.

If the new citizens sworn in during Constitution Week registered right away, they would be eligible to vote in the election. Michael Preller, who moved to the U.S. from Germany twenty-eight years ago, told me that he planned to register as soon as possible—his son was running for city council in Page, Arizona. “And, you know, every vote counts,” he said, grinning. In Yuma, the county recorder’s office was handing out voter-registration forms. An older man with a small American flag tucked into the pocket of his khaki shirt filled one out. “I want to cry,” he told me. “I’m too happy.” He said that he had moved to the U.S. from Mexico in 1979; both of his adult daughters, who attended the ceremony, had been born here. “I’ve never voted. Not even for ‘America’s Got Talent,’ ” one of them admitted. Her sister gave her a scandalized look.

Ambika Sharma recited the Oath of Allegiance alongside her husband, Parikshith Kumar. “I’m so excited to vote,” Sharma told me. “You live here, you’re paying taxes, but you don’t have a voice. People are, like, ‘Now you’ll have to do jury duty!’ But in what other country do you get to participate in the process in this way? You don’t in India.” She looked out over the canyon, where a large bird turned in a slow circle. “There’s a Hindu concept, karmabhoomi—it means the land where you work, where you’re creating your karma,” she said. “Why not invest in that place?”

New citizens pose for pictures at the rim of the Grand Canyon.

Sourse: newyorker.com