Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Hilton Als

Staff Writer

You’re reading the Goings On newsletter, a guide to what we’re watching, listening to, and doing this week. Sign up to receive it in your in-box.

I didn’t know Teresita Fernández’s work until recently, but that’s not entirely a bad thing. She is not one of the glut of artists who get overexposed as they rush to fill the demands of the contemporary-art market—make it shiny, political, and new—while not worrying much about internal growth. That’s what makes looking at Fernández’s work in the exhibition “Soil Horizon” (at Lehmann Maupin, through June 1) feel like a new experience—she’s dug deep into her own internal life and consciousness and returned with something fresh and profound and nourishing.

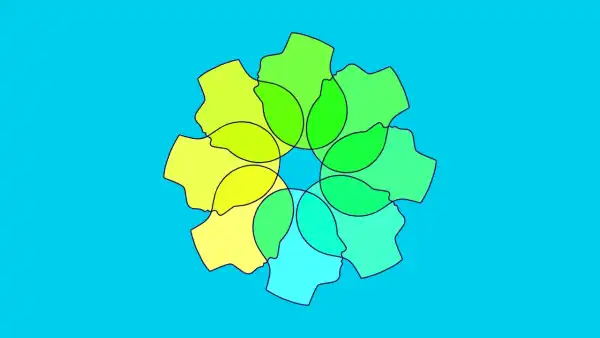

Detail of “Soil Horizon 5.”Art work by Teresita Fernández / Courtesy the artist / Lehmann Maupin

Born in Miami, Florida, in 1968, to Cuban parents, Fernández incorporates natural resources tied to colonization into work that examines landscape and place; she was awarded a MacArthur grant in 2005. There are a number of emotional elements in the current show, autobiographically speaking, that harken back to her fascinating early examinations of memory. Like the late Cuban-born artist Félix González-Torres, Fernández is interested in the politics of displacement, and what happens to the colonized soul. Although her work bears no visual resemblance to González-Torres’s—such as his haunting photograph of his empty bed sans AIDS-stricken lovers, or his jigsaw series, which depicted his family on a series of puzzle pieces sealed in a plastic bag—Fernández is, like González-Torres, a kind of minimal poet, who is now working in a beautiful new register.

In addition to showing her film work for the first time, and displaying a monumental sculpture titled “Sunrise(Sunset),” which connotes burial grounds, the now fifty-five-year-old artist uses copper panels for the resonant and reflective wall sculpture “Soil Horizon 5” to describe the earth’s interiority—the layers that make up the ground we stand on (or get buried in). Charcoal, volcanic sand, and iron-rich red sand are layered on the panels with a naturalness that doesn’t so much interfere with how nature arranges itself as show us what it can look like—and yield—when the artist works from her own interior self and imagination.

About Town

Off Broadway

“Macbeth (an undoing),” Zinnie Harris’s highly cerebral and sometimes revelatory adaptation of Shakespeare’s tragedy, follows Lady Macbeth (played here by the fascinating Nicole Cooper, whose every thought comes rushing forward from her face) into the gaps where the Bard has her disappear. The new play is bracketed by meta-theatrical devices: Lady Macbeth has a chambermaid, Carlin (the very funny Liz Kettle), who also acts as a stagehand and an emissary to the audience, offering monologues that play up the class conflict between crew and cast, servant and master. This arrangement aptly reveals a roiling disquisition on power, sex, delusion, and fantasy.—Vinson Cunningham (Polonsky Shakespeare Center; through May 4.)

Dance

Since 2008, Danspace Project has invited artists to curate a multi-week series of performances, talks, and classes called a Platform. For the latest, “A Delicate Ritual,” Kyle Abraham has asked participants to consider the roles of nature, love, and prayer. On May 2, events begin, with a program shared by Shamel Pitts and the vocalist-songwriter Nicholas Ryan Gant, then continue, through June 8, with pairings of emerging and established choreographers (Taisha Paggett and David Roussève, Vinson Fraley and Bebe Miller), as well as a memorial for Kevin Wynn, a beloved choreographer and teacher of many, including Abraham.—Brian Seibert (Danspace Project; May 2-June 8.)

Broadway

Illustration by Keith Negley

In an early scene of “The Outsiders”—the new Broadway musical based on S. E. Hinton’s 1967 novel and on Francis Ford Coppola’s 1983 movie, directed by Danya Taymor, with a book by the always-busy Adam Rapp, with Justin Levine, and music and lyrics by Levine, Jonathan Clay, and Zach Chance—a young, searching kid looks up adoringly at Paul Newman’s face beaming out from a movie screen. He’s Ponyboy (Brody Grant), and his life in Tulsa, Oklahoma, is circumscribed by constant skirmishes between his group of outsiders, the Greasers, and the town’s semi-fascist preppies, the Socs. The story is dense with the kind of tragedy that leaves audience members sniffling in their seats. Even when individual lines of dialogue swing dangerously close to corniness, Taymor’s painterly direction and Rick and Jeff Kuperman’s choreography give the show a glow of hard-earned authentic reminiscence.—V.C. (Bernard B. Jacobs; open run.)

Classical Music

With more than fifty concerts over three days in Brooklyn, this year’s Long Play Festival, organized by Bang on a Can, celebrates contemporary music in general and minimalism in particular. The latter includes Steve Reich’s “Music for 18 Musicians,” David Lang’s haunting “the little match girl passion,” and Philip Glass’s Piano Études (in new arrangements for accordion). The programming honors past path-breakers while making space for newer ones, such as the microtonalist Peter Adriaansz and the jazz experimentalist Josh Johnson. The flutist Claire Chase, who is on a multiyear odyssey stretching her instrument’s possibilities, elegantly bridges the two worlds, with excerpts from a new piece by minimalism’s white-bearded forefather Terry Riley.—Oussama Zahr (Various venues; May 3-5.)

Jazz

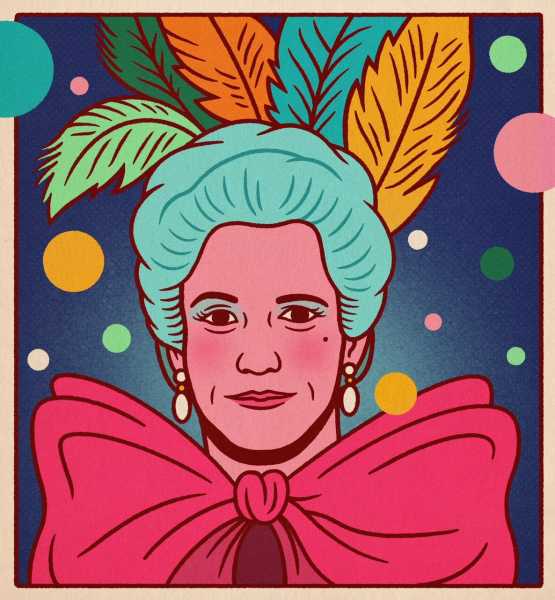

Photograph by Vincent Haycock

Since Kamasi Washington’s appropriately titled 2015 album, “The Epic,” a hundred-and-seventy-three-minute triple disk of far-reaching, mind-expanding spiritual jazz, the saxophonist has only grown more tremendous, in sound and stature. He was already a fixture on the L.A. music scene, committing to the jazz collective West Coast Get Down and working with the experimental label Brainfeeder, when he played a pivotal role as a key session musician for Kendrick Lamar’s “To Pimp a Butterfly.” These days, Washington is one of the most ambitious bandleaders out there, and his playing is as forceful as his vision. This show kicks off the release of his new LP, “Fearless Movement,” which he has referred to as his “dance album,” shifting focus from celestial bodies to physical ones.—Sheldon Pearce (Beacon Theatre; May 4.)

Movies

The director Jane Schoenbrun is making a notable career dramatizing young people losing and finding themselves in mass-media rabbit holes. In their previous feature, “We’re All Going to the World’s Fair,” from 2021, a teen-ager seeks freedom and faces danger in an all-consuming interactive video game. Schoenbrun’s new film, “I Saw the TV Glow,” set mainly in the nineteen-nineties, is centered on two lonely suburban adolescents, Owen (played younger by Ian Foreman and older by Justice Smith), and Maddy (Brigette Lundy-Paine), who are obsessed with a TV series about teen superheroes. Owen, an introvert who craves a feeling of belonging, riskily imagines himself into the series—which inspires the rebellious Maddy to take reckless action. Schoenbrun tells their stories in images that blend eerie chills and tender warmth while keeping the object of their obsession in skeptical perspective.—Richard Brody (In theatrical release on May 3.)

Pick Three

Every theatre in town seems to be opening a show; here are Helen Shaw’s top picks.

1. Amy Herzog’s oddly buoyant slice-of-dying play, “Mary Jane,” is on Broadway at last. A single mother (Rachel McAdams, still feeling her way) raises a child with terrible medical burdens; wry and humorous women—played by theatrical treasures like April Matthis, Susan Pourfar, and Brenda Wehle—help her maintain her spirit. The show (at the Samuel J. Friedman) is full of grief, but the sensation of it goes up and up.

2. In Shaina Taub’s rip-roaring musical “Suffs” (at the Music Box), Taub herself plays Alice Paul, who rallied American suffragists in a new, “unladylike” fashion; Nikki M. James plays Ida B. Wells, who decried the stifling whiteness of Paul’s movement; and Jenn Colella plays Carrie Chapman Catt, an older leader whose more conciliatory tactics also helped secure the 19th Amendment. The musical succeeds at a thrilling, all-hands-on-deck level: “Suffs” readies you to both look inward and march on.

Illustration by Bene Rohlmann

3. Virginia Woolf’s novel “Orlando,” in which an Elizabethan nobleman (Taylor Mac) lives for centuries, changing in their course from man to woman, is a bear to adapt, but Sarah Ruhl’s 2010 play manages it with a skater’s grace. She’s abetted immensely by Will Davis’s gorgeous, gender-liquid production, for Signature Theatre, and Mac’s laughing delivery, but I was most moved by Nathan Lee Graham’s Queen Elizabeth, half in emerald tracksuit, half in golden farthingale, gliding forward out of death for one last kiss from her favorite.

P.S. Good stuff on the Internet:

- How to be a bather

- Halal-cart rundown

- Tavi Gevinson on Taylor Swift

Sourse: newyorker.com