Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this storyYou’re reading the Food Scene newsletter, Helen Rosner’s guide to what, where, and how to eat. Sign up to receive it in your inbox.

Memory is a powerful attractant, even if the memory isn’t our own. Something draws us inexorably to nostalgia, to the soft focus of hindsight, the comforting narrative completeness that can be found in the rearview. This is never more true than at a restaurant, where you sit inside the story, smell the story, eat the story. For all of its allure, though, nostalgia is a tricky element for a restaurant to trade in, and a risky thing to rely on. Storytelling can get people in the door, it can set the mood, but it’s not the same thing as substance: a restaurant has to be good as a restaurant, not just a set piece, to get you telling your friends about it, or to get you back a second time.

A Martini.

Spaghetti and meatballs.

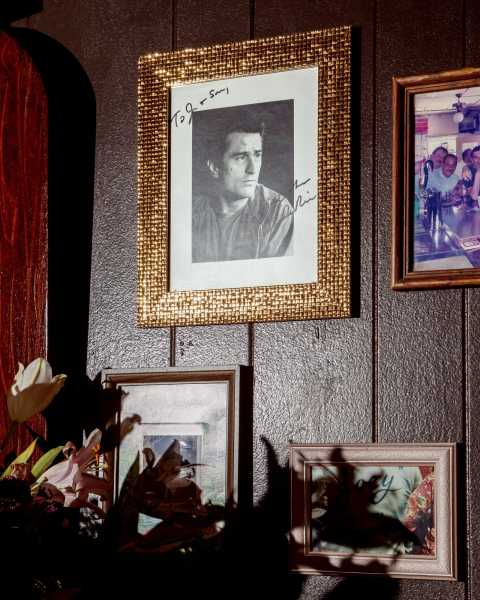

JR & Son, which opened in Williamsburg last month, seems on the surface to be a potent exercise in calling up the past. It occupies the former home of a bar of the same name, an unassuming joint that dated to the seventies, having, itself, taken over the spot from a venerable bar called Charlie’s, established in 1934. Now under the ownership of a restaurateur duo, Michelle Lobo and Scott Hawley, and the restaurant designer Nico Arze, the place has been newly restored but still looks preserved from some long-ago heyday. There are red leather booths and checkerboard floors, the wood-panelled walls decorated with black-and-white photos of living and long-dead luminaries. Ceiling fans gyrate lazily. The air smells dark and sweet, like oregano and red wine.

You’d expect to have a certain kind of meal in a room like this: red-sauce Italian, all the classics, fairly insipid but not without charm, any shortfalls on the plate made up for by the accumulated dignity of a near-century of operation. You’d expect to say something like “It’s not very good, but it’s perfect, you know?” So it’s a shock—an honest-to-God shock—to settle in for dinner at this new-old restaurant and find that every bite, from the bread basket on down, is just spectacular—rigorous, referential, playful, precise. An arancini salad features the fried balls of gooey rice with smoked mozzarella, shrunk down to crouton size and tossed with bitter chicories and herbs. Chicken parm is a golden sun, crackly and fried, its blanket of Calabrian-chile-spiked tomato sauce fresh and scorching as the summer sun; a scattering of sesame seeds in the cutlet’s breading summons the dish’s alternative identity as a sandwich, on a squishy seeded roll. A clever appetizer of clams “alle vongole” finds the mollusks, on the half shell, stuffed with tiny portions of pasta in white clam sauce.

The room has a patina of use and an old-fashioned duskiness.

All of this is the work of Patricia Vega, who until recently was the chef de cuisine at Thai Diner, and the connection makes perfect sense: Thai Diner is one of New York’s most reliably gobsmacking restaurants, one of a handful of places in the city where every single dish on the menu is an absolute star. At JR & Son, Vega comes close to achieving a similar all-hits-no-skips lineup. The food, while definitively Italian American, isn’t limited to the paint-by-numbers expectations. There’s a whisper of fish sauce in a side of green beans. Gentle stracciatella gets funkified with black-olive caramel and wisps of orange bottarga. What look like fluffy little zeppole are actually onion rings, with a zippy pink sauce of bomba chiles and aioli. Crab salad, served on ice, with a halo of Club crackers, calls back to a mid-century supper club. The triangolini, three-sided pasta envelopes stuffed with artichokes, are almost comically enormous; a mere four to an order is more than plenty. Some dishes don’t quite live up to their big ideas: a pot of mussels steamed with chickpeas and spicy ’nduja arrived a little on the dry side, and a Caesar salad, topped with crunchy bits of anchovy, the lettuce blackened on the grill, was blobbily overdressed. But even the bread basket, the creation of the pastry chef Amanda Perdomo, is something of a riot, which on my visits contained two olive-studded wedges of focaccia and two tiny, butter-glossed Parker House rolls, yielding and yeasty and drowning in shaved parmigiano.

Helen, Help Me!

E-mail your questions about dining, eating, and anything food-related, and Helen may respond in a future newsletter.

One of the most tangibly old-fashioned things about JR & Son is its dimness: the building, on a prime corner spot, has just a few tiny windows. As both a supper club and a local dive, it was a place meant for being inside of, not looking out from. In the early-dinner hours, before nightfall, white slashes of sunlight slip through cracks in the horizontal blinds and play through the dusky interior like a laser show. The updated room has retained a patina of honest, unrelenting use, traces of thousands of past nights out. The squeak of the booths, the clink of the Nick and Nora glasses when your Martini arrives—they’re not illusions or re-creations. The spaghetti and meatballs have a retro appeal—spaghetti, you crazy bastard, making a well-deserved return to the ranks of serious pasta—but the toothsome noodles, made daily, taste both a hundred years old and born today.

Arancini salad.

Old framed photos add throwback appeal.

The staff runs a tight ship—demand is high, reservations are scarce, and the restaurant holds back a few tables for walk-ins and locals—so it’s not exactly a place to linger. Still, it would be a mistake not to make time for dessert, which is also overseen by Perdomo. The menu is brief and, on paper, somewhat predictable: a tiramisu, Italian cookies, an ice-cream sundae. But, as with the fruits of Vega’s savory kitchen, the dishes all go gleefully off-piste in the details. There are floral notes of orange zest in the tiramisu, and the fruity-bitter taste of espresso is enhanced and complicated with fruity-bitter amaro. A slab of Italian rainbow cookie is the size of a greeting card, dense and soft as chenille, with the traditional almond flavor traded for coconut, an audacious violation of the rules of a treat famous for its comforting consistency. (Like a surprising portion of the menu, the desserts are vegan.) This is JR & Son’s whole thing: collapsing the space between looking back and looking forward, gesturing to the hazy perfection of memory, and then pulling you lovingly, delightfully, with a polite yet firm reminder that they’ll need the table back in about fifteen minutes, right back into the thrill of the here and now. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com