Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

For his third published collection, “The Children’s Melody,” the artist Eli Durst made a return to his old grade school in Austin, Texas. The structure, built during the New Deal, seemed amazingly untouched, save for the addition of computers. The lunchroom still smelled familiar. One of his past instructors remained, urging pupils to form a tidy queue. “It brought me back to being eight years old,” Durst confided.

“Elementary School Audience,” 2023.

Durst favors capturing moments of activity—the communal, organized happenings that fall between obligation and sheer leisure. His initial book, “The Community,” began as a study of church undercrofts and then grew to encompass various flexible areas used as backdrops for religious gatherings, scouting groups, team-oriented games, and amateur theatricals. These typical American customs, viewed through Durst’s inquisitive, unhurried lens, come across as enigmatic, surprisingly heavy with meaning. A group of arms reaches for a piece of bread; a woman, seen from the back, joins hands with a pair of dummies. The photographs underscore the strangeness and occasional preposterousness inherent in our efforts to comprehend ourselves and one another.

“Props, Texas State History Play,” 2023.

“The Children’s Melody” has a more restricted scope, concentrating on youths—roughly spanning the elementary-school years to college—engaging in diverse group activities: R.O.T.C., debutante balls, stage productions, cheerleading drills, Irish folk dance. “I’ve always gravitated toward photographing shared activities that involve both practice and a final presentation. Where there’s a sense of development, of learning and assimilating, and then expressing outwardly,” Durst remarked to me. He finds interest in “the methods by which we pick up behaviors, acquire perceptions of gender roles or values—the ways they integrate into our being, and our subsequent display of them for others.” The images comprising “The Children’s Melody” were predominantly captured in Texas, a state that, notwithstanding its supposed valorization of personal autonomy, is resolute about influencing its young. The region accounts for over a quarter of the country’s documented book censorship; numerous college networks limit talks on transgender and nonbinary identities; and a recent law mandates the prominent display of the Ten Commandments in every classroom in the public school system. Durst takes an interest in establishments that aim to educate and mold children, though these are not portraits of conformity; within “The Children’s Melody,” indoctrination is perpetually uncertain and deficient.

“Curtain Peek,” 2023.

“Irish Dancer,” 2023.

Durst’s sophomore release, “The Four Pillars,” was largely produced during the COVID outbreak. Its ambiguously arranged scenarios, many focusing on a New Age self-help circle Durst had tracked since his church-basement days, leaned into the forced artificiality of that era. Taking pictures for “The Children’s Melody” felt like “a coming back into the world,” with all its bewildering complication, Durst told me. The undertaking became defined after Durst captured a picture of an energetic set of second graders vocalizing. The resultant shot presents a loose configuration—various youngsters position their linked arms ahead, with fingertips touching—yet the total impact is one of cheerful, vivid disorder. Children glance left, glance right; they sing eyes shut; they peer intently at their neighbors; it’s plain they are lost in their thoughts. It stands as a representation of trying to herd singular people into a collective, the responsibility of educators, mentors, and troop conductors. As portrayed in Durst’s work, such efforts are invariably partially effective. Progressing through the book, some of the children displayed are older and exhibit greater command over their exterior displays, yet fragments of oddity or dissonance invariably crop up.

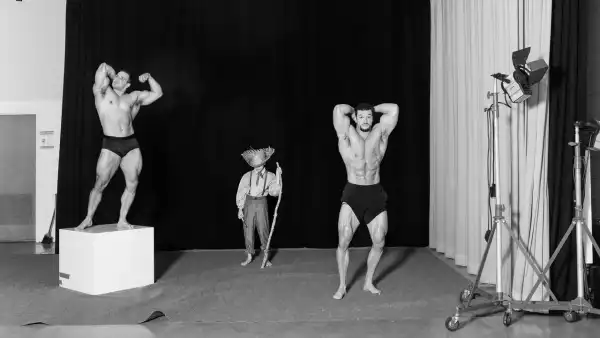

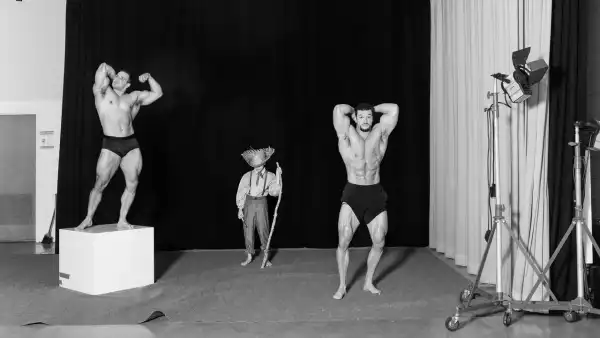

“Three Brothers,” 2025.

The youths captured in Durst’s shots try out instruments, crowns, military attire, graduation robes, and miniature formal neckwear, which they inhabit with assorted amounts of self-assurance. Some come across as being at peace within their grown-up costumes. A girl adorned with makeup and a golden-blond wig advances, visage shining and chest puffed out, as though moving into an imagined spotlight. At other times, an outfit seems to heighten fragility: An R.O.T.C. trainee in full camouflage nervously glances to the side of the shot, at an unseen menace. Durst’s shots capture the otherworldly temporal quality in young countenances, the way they can at moments seem much older, or younger, than their actual years.

“Two Couples, Cotillion,” 2025.

One of the volume’s most memorable images is also among the simplest. A quartet of children in slightly formal dress are arranged by a wall. They are roughly of the same years in age—perhaps twelve—but of significantly differing height. The next-tallest, a boy, directs a firm gaze toward the camera, that of a budding class leader. The tallest, a girl in a layered skirt, appears more hesitant. Their characters are apparent, but yet unformed; their prospective adult selves flicker in and out of awareness. This image is one of several taken at a cotillion, a mostly Southern custom involving manners courses and dance instruction for adolescents. Its contrived and orderly nature makes it a fitting Durst subject. While much about cotillion seems outdated (after all, who needs to know how to cha-cha in current times?), Durst’s pictures are devoid of negativity. Fundamentally, cotillion focuses on children connecting with one another personally. (My individual cotillion memories are rooted in seventh-grade melodramas; I have lost track of the dance sequences.) The children are not yet certain what it signifies to them, and Durst shares that doubt alongside them.

“Communion,” 2023.

“Daisy, Black Eye and Broken Nose,” 2024.

“Praying, Church Youth Group,” 2023.

Durst captures images digitally, using several remotely-operated flashes that he sets up for a faintly off-kilter result. The monochrome images are on occasion back-lit, on occasion lit by directed light originating from unforeseen angles. In one shot, a light burst manifests as a bizarre sphere within a mirror, reminding the observer of the photographer’s existence. The rooms are tidy but worn; their dilapidated areas reveal the buildup of time, the countless children who have occupied the chairs, executed the actions, rehearsed those moves. One among the initial images in the compilation portrays a vacant school auditorium. An ascending platform spreads across the stage, bordered on one side by the Texan and American banners, and on another by a synthetic tree in a hefty pot. The curtain cracks slightly, hinting at an unseen offstage. There are theatrical lights, a microphone, an amplifier. Nothing in this scenario verges on the surreal, yet the image carries a dreamlike force, a sort of quintessential intensity prompting recollection of the frequency by which anxiety dreams return me to comparable locales.

“Cheer Pyramid,” 2024.

The preface of “The Children’s Melody” comes in the form of a concise, educational poem concerning children’s pursuits, penned in the sixteenth century by Henry VIII. The king compliments “feats of arms” coupled with other “good disports” deemed “pleasant to God and man,” an honorable diligence warding off the peril of “vice.” Worrying about youths’ spare time is a common adult obsession, antedating Minecraft by centuries. Barely any modern tech appears in Durst’s images. Instead, kids put on performances, compete, and observe each other. They inhabit spaces with brick walls, collapsible chairs, false ceilings, bare ductwork, and scarred laminate at the base of a cracked door. A projector is positioned on a scuffed desk, hoisted up by a pile of religious books. The wooden gymnasium floor reflects so much light that you could practically hear sneakers squeak. These locations possess a timeless air, yet the emotions conjured by the shots have more layers, and a feeling more unsettling, than pure sentiment. “I distinctly recall being quite anxious as a kid, especially concerned about, you know, my true identity, my future career, whether I was a morally upstanding person,” Durst confided. This sense of unease surfaces constantly throughout the volume, most acutely in a wide-angle portrayal of a group of cheerleaders training in a gymnasium. Five sets of girls clad in matching uniforms press against each other, arms upraised, each group holding another girl balancing on a single foot. Cheerleading is regularly depicted as a representation of flawless grace coupled with symmetry. Here, the effort takes center stage. What is captured is a portrait of powerful thighs alongside strain, revealing all of the work going into a human structure liable to collapse at any

Sourse: newyorker.com