Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

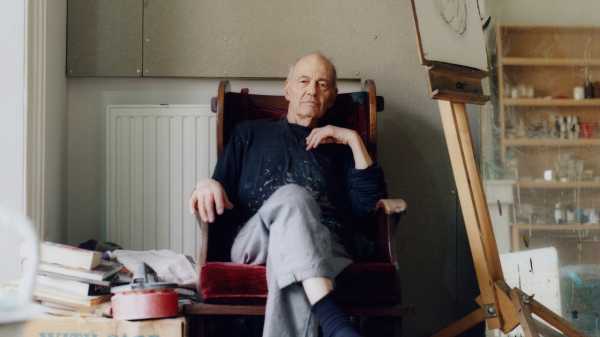

The name of Frank Auerbach, the British artist who died on November 11th, at the age of ninety-three, is not especially well known in the United States. MOMA holds five of his works—one oil painting, two drawings, and two prints—but none are currently on display. The fame, not to mention the infamy, that settled upon his friends and fellow-artists Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud eluded Auerbach, not that he was the kind of guy to seek the spotlight’s glare. Although he was no hermit, the intensity of his diligence—he took one day’s holiday a year—seemed to set him apart and alone. He once said, “I think of painting as something that happens to a man working in a room.” He could be talking about a heart attack.

Much of the time, Auerbach was joined and tempered in his solitude by a model. To sit for him regularly, as several people did, sounds like a test of both stamina and loyalty. One such model, Estella (Stella) West, often identified as E.O.W. in Auerbach’s portraits, was a widow with three children, whom he’d met in the late nineteen-forties. He became her lodger and her lover, and she later recalled putting a joint of meat in the oven, on a low heat, and posing for a couple of hours while it cooked. (They then sat down with the children to eat it: a pleasure fully earned.) Another woman, Julia Yardley Briggs Mills, sat for Auerbach twice a week for forty years. “To paint the same head over and over leads to unfamiliarity,” he said. “Eventually you get near the raw truth about it.”

In almost any Auerbach oil painting, early or late, rawness is thick on the ground. So dense, so clotted, and so busily heaped is the pigment that you’re not sure whether to gaze at it, lick it, chew it, or file a weather report. The best option would be to reach out, with or without permission, to touch the picture’s surface, tracing the whorls and the smeared grooves. Somebody with impaired vision, conducting a fingertip search, might gather as much as—or more than—a viewer with perfect sight who merely looks. There are full-length and half-length portraits by Auerbach, but, in truth, the real action starts from the neck up. In “Head of Leon Kossoff” (Kossoff was another painter, and a close friend of Auerbach’s), from 1954, or in “Head of E.O.W.,” from the following year, the faces, looming out of the gloom, are turned aside and downward, locked in thought. Eyes are dark holes. Light falls largely on cheekbones and brows, as if Auerbach were gauging the best access to the brain. Is it in tribute to this quest that Freud’s superb portrait of Auerbach (1975-76) should be a skull-length image, peering down into the bulging, worried landscape of his pate? And where, and when, did those worries conceivably begin?

To call Auerbach a British artist is correct, but it was not always thus. To be precise, he has been a British citizen since July 16, 1947, when he received his naturalization papers. Before that, he was German—born in Berlin, in April, 1931. He was the only child of middle-class Jewish parents; his father, a patent lawyer, was the son of a rabbi. When he was seven, young Frank was sent by ship to England, for his own safety, to take up the offer of a place in a well-run school in the countryside. His mother stitched little red crosses onto the clothes that did not yet fit him, into which he would later grow. Auerbach never saw his parents again. They died at Auschwitz.

The paradox is that, treated with kindness, and encouraged by sympathetic teachers, the orphaned boy enjoyed the rest of his childhood. “I think I did this thing which psychiatrists frown on: I am in total denial,” the adult Auerbach maintained, adding, “It’s worked very well for me.” Denial itself, needless to say, can be a driving force, and the frowning shrinks might point to the roiling energies of an Auerbach painting, and to his obsessive habit of scraping away the remains of a day’s brushwork and beginning afresh on the morrow. Is that purposeful, or paranoid? “I feel myself to be Jewish in the sense of being a person, in all other respects exactly like everybody else, who has been made to feel uneasy,” Auerbach said. Few modern artists do so much to persuade us that creative endeavor is a struggle—an anxious wrestling with the stubborn materials to hand, and a determination to plow on.

The teen-aged Auerbach left school, went to London, and took root there for the rest of his life. In reading “Frank Auerbach: Speaking and Painting,” a fine book by the curator and art historian Catherine Lampert, who also modelled for Auerbach, the impression one forms of him in his youth is that of a lean and hungry figure, often poor, yet impelled by an excited desperation. (His work, however heavy with shadows, never tells of sunken spirits. You are more likely to feel eagerly baffled by it than benumbed.) The city around him still bore the wounds of war, and the jamming together of wreckage and reconstruction had its enduring effect, as Auerbach recalled:

There was a curious feeling of liberty about because everybody who was living there had escaped death in some way. It was sexy in a way, this semi-destroyed London. There was a scavenging feeling of living in a ruined town.

As with many poets and painters, you catch the murmur of a hard heart in their willful knack of examining a crisis, or a collapse, for its artistic opportunities. Auerbach admitted as much. “If one is told that the man next door has been poisoned, or that someone has been run over in the street, one tries to behave decently but the real instinct is to get back to the studio and the brushes to make sense of these events,” he said. I doubt if many Londoners, confronted with a flattened home, found anything sexy in the loss, but Auerbach turned it to fruitful account, aiming to unearth what he called “a secret internal geometry.” You meet the results in unexpected places. Like Freud, he used the National Gallery, in London, as an unfailing resource, sketching there year after year, and striving to breed something new out of the Old Masters. Hence “Study after Deposition by Rembrandt II” (1961), in which the space—much bigger than that occupied by the compact original, “The Lamentation over the Dead Christ”—is dominated by the cross and the ladders that lean against it. Golgotha leaks into London. Calvary is reconfigured as a building site. That takes nerve.

For decades, Auerbach had a studio in Mornington Crescent—north of the British Museum, east of Regent’s Park. This was his parish. He rarely ceased to roam it, reconstituting its roads and slopes, as witnessed in “Frank Auerbach: Portraits of London,” an exhibition that opened at the Offer Waterman gallery, in Mayfair, in the month before his death. The earliest painting on display, “Primrose Hill, High Summer,” dates from 1959; the latest, “Way Out,” from 2019-20. The show supplies a bracing contrast to “Frank Auerbach: the Charcoal Heads,” which, this past year, assembled a series of his monumental drawings at the Courtauld Gallery, off the Strand, on the north side of the Thames. Painted exteriors or drawn interiors, townscapes versus headscapes: take your pick.

At the risk of perversity, if not heresy, I admit that, given a choice of Auerbachs, I would take a charcoal drawing over an oil painting, any day. (Mind you, I veer the same way in regard to Seurat. That really is perverse.) Once, I almost did. In the nineteen-nineties, I came upon one of the charcoal heads for sale and calculated that, if I sold all the pictures that I owned, plus my car, and gave up vacations for a few years, I could just about afford to buy it. Wiser counsels prevailed, and the plan was dropped: an act of cowardice that I now regret, not because the work would have gained in value as an investment (though it would have done, many times over) but because I would have been investing in Auerbach’s act of courage—the record of his unremitting efforts to seize what struck his gaze.

The fallout of those efforts is discernible in the finished works. Much as Auerbach wiped away daily deposits of oil paint in preparation for the next assault, so he deployed an eraser (often a hard one, like that used by typists) to rub off most of a drawing, leaving little more than the relic of an image. The difference is that paper, being friable, tends to fray and to tear—a problem partly solved by Auerbach when he stuck two sheets of paper together, so that breaking through the upper one would allow him to persist in his task with the lower. Elsewhere, as in a self-portrait from 1958, he patched up the damage by applying rectangles of fresh paper, often with jagged edges; what emerges is more than a palimpsest, too brutishly there to be ghostly. It’s like the portrait of an injured man who has had to improvise his own healing as he goes along. Charcoal, we should remember, follows burning. Strangest of all are the late-blooming grace notes: the sudden strokes of pink chalk, of all things, that jut into the frame at the foot of “Head of Julia II” (1960). As Auerbach wrote, with laudable simplicity, in a statement that accompanied six of the charcoal heads, “I find it all very difficult.”

That is what Auerbach did, and does: he gets to you. The angle at which he bears down upon the world, and the dark light that he shines on it, become contagious. Last year, in the National Museum in Stockholm, I was stopped dead by another Rembrandt, one of the last things he ever painted—“Simeon in the Temple,” from around 1669—and said to myself, “Auerbach.” Focus on the balding dome of the saint’s forehead, and the slits of the half-closed eyes; the paint is not piled up by Rembrandt as it is by Auerbach, but it is worked and roughly reworked, by both men, to the last gasp. As for the pit of the mouth, it must be opening, because, thanks to the Gospel of St. Luke, we know the words that Simeon is about to speak, as he holds the Christ child in his arms: “Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace.” Having stayed alive and waited for this moment, he is now free to die. Frank Auerbach, too, has made what one prays was a peaceful departure. Every struggle finds its end. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com