Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

I have been in New York for twenty-two years and still get the weird feeling that I am living in a dream. Not living a dream—the city can be yucky and hard—but inhabiting a blur of the fictional and the real. My old, brick apartment building in Brooklyn, my decrepit subway station, my go-to pasta place, my office’s cloud-high view of lower Manhattan—these scenes and scenes like them are so commonplace in films, art, ads, and TV that they look uncanny, even as I’m moving through them.

The Singaporean photographer who goes by the single name Nguan has often felt the same way. He was living in SoHo after college, intending to be a filmmaker, when 9/11 happened. Outside his apartment, on Sullivan Street, he used an early Canon digital camera to document what he saw. “My photographs were really bad,” he told me. “But when I wanted to tell people about that day, nothing I wrote or talked about could convey that reality better.” This was what led him to photography. He found the city full of willing subjects, both new and canonical. It was impossible to improve upon the Coney Island pictures of Diane Arbus or Bruce Davidson, for instance, but Nguan committed himself to shooting and reshooting the beach, the boardwalk, the swimmers, the Ferris wheel. “It’s interesting to be able to measure yourself against all the great photographers,” he said. “I think of the work I make in New York as cover songs.”

Nguan moved back to Singapore many years ago—his pastel images of apartment dwellers, and of streets thick with bougainvillea, are well known—but still spends a couple of months in New York every spring or summer. In 2013, after his father died, he found a photograph of him standing on a boat, in view of the Statue of Liberty. This made Nguan think about the Staten Island ferry, which passes the statue on its path between Staten Island and Manhattan. The small fleet of boats, old and new, runs twenty-four hours a day and serves more than sixteen million passengers a year. It has been part of New York City’s public-transit system since 1905, but dates back further in concept, to a Lenape network of canoes and landings, and piraguas run by European settlers. Nguan had wanted to do a project about commuters in New York, but the subway was too cramped and dark; he works only with natural light. On the Staten Island ferry, as evening approached, the sun’s rays would “cut right through the boat and illuminate everything within,” he said. “Even the most ordinary, mundane person can look iconic.” The boats were rarely full, so he had space enough to make pictures of individuals, couples, and rows of family and friends.

His new collection, “All the Dreamers,” begins with portraits of sleep. In a corner seat, a commuter wearing a cozy blue scarf and a “BRONX” beanie clasps her hands and closes her eyes, lulled by the glide across water. Light pours through a nearby window, drawing a rounded trapezoid across her face and the sign above her, indicating exit, elevator, and snack bar. The ferry’s 5.2-mile journey is non-stop, and takes about twenty-five minutes—just enough time for a nap.

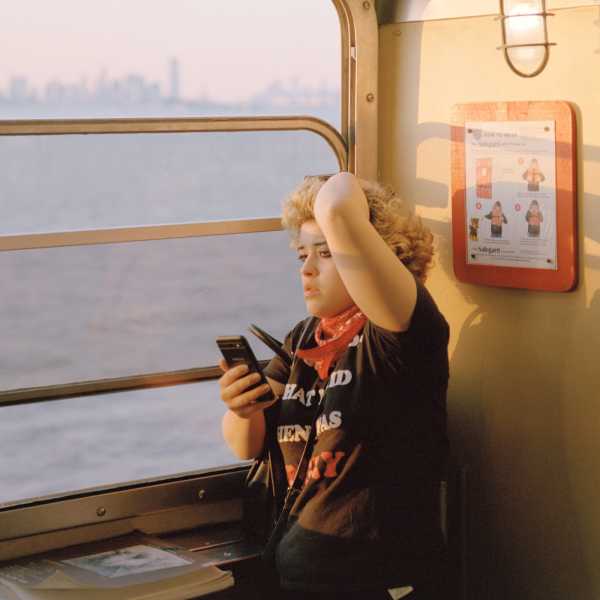

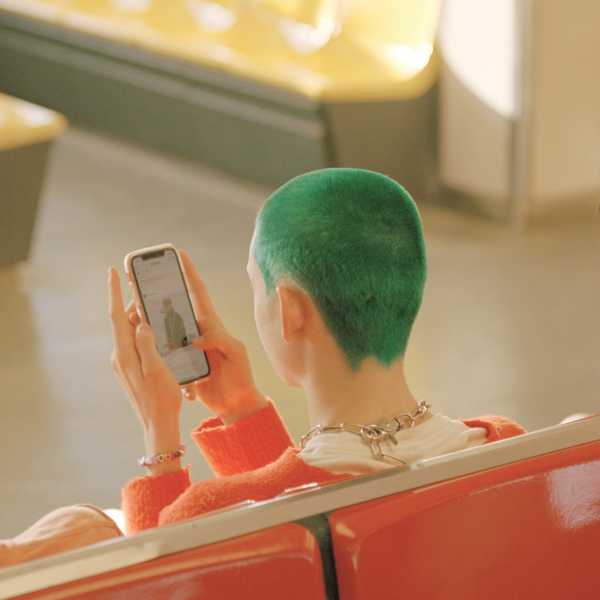

Of the waking, Nguan has more to say. The backs of people’s heads attain a brilliant liveliness. On the windy deck of the boat, a girl’s long blond hair is tossed into the shape of a wild chrysanthemum. Another girl, inside, wears a perfect bun, no strand out of place. Her ginger coloring matches the orange of the molded-plastic seats. There’s a passenger with a bright-green buzz cut (in sharp contrast with that same orange), one with a platinum wig, a baby-blue turban, a sparkly hijab, a graduation cap, a fez, very big headphones. Clothing suggests occupation: a construction worker, a nurse, a deliverista. The passengers talk and eat sandwiches, they drink coffee, read books, and pray. They stare at their phones, of course. They carry all sorts of things, from skateboards and rolling luggage to babies and cameras.

The pictures are fairly close, a product of Nguan’s technique and persistence. He always uses the same, simple setup: a Fuji 6×9 medium-format rangefinder, loaded with actual film. He moves his body to get the right distance, and keeps the camera to his face, so that his subjects aren’t caught totally unaware; he doesn’t ask for permission. The sound of the shutter invites eye contact, and sometimes results in an organic series. In one picture, amid a small crowd assembled at the windows of the ferry, a young woman carries a boy in her arms. It’s sunny and hot. Both gaze outside, maybe at the Statue of Liberty, though the child’s line of sight is slightly lower than hers. The next picture is nearly identical, except for the boy, who tilts his head and looks straight into the lens.

To make such portraits, Nguan became a commuter in his own right, taking hundreds of trips to and from Staten Island between 2014 and 2024. Some days were more productive than others. There had to be the right combination of boat and passenger, action (or stillness) and light. He much preferred the older boats, with their colorful interiors, to the newer, astringent ones. (All of the ferries are bright orange on the outside, which helps with visibility in fog.) He would wait at the terminal to board the John F. Kennedy, commissioned in 1965, with its aqua-blue walls and chocolate-brown bench seats, or the Samuel I. Newhouse, commissioned in 1981 and named after the publisher of the Staten Island Advance. (The same family owns The New Yorker’s parent company, Condé Nast.) The Newhouse is the largest passenger ferry in the country, with a capacity of fifty-two hundred.

The J.F.K. was decommissioned in 2021, at a time when the pandemic kept Nguan from travelling. The following year, it was acquired at auction, for two hundred and eighty-thousand dollars, by “Saturday Night Live” cast members Pete Davidson and Colin Jost, who, along with a business partner, announced plans to turn it into a floating comedy club and restaurant. (Jost and Davidson were born on Staten Island.) “I was quite relieved that someone bought the J.F.K.,” Nguan told me. The alternative would have been a full scrapping, which is what befell another Staten Island ferryboat, the Andrew J. Barberi. Nguan had loved to shoot its “McDonald’s color” seats of red and marigold. When “Entertainment Tonight” asked Davidson for an update on the J.F.K., in June of 2023, he explained that he had “no idea what’s going on with that thing,” and that he and Jost had purchased it while “very stoned.” Jost denied this, writing on Instagram, “Is it worse that I was actually stone-cold sober when we bought the ferry?” The pair did make some use of the vessel last fall, during New York Fashion Week, when it became a runway for Tommy Hilfiger’s nautical designs and a performance by some of Staten Island’s very own Wu-Tang Clan.

I was last on Staten Island to speak with workers at JFK8, the first Amazon warehouse to form a union in the United States. Some of the workers I met commuted locally, from various neighborhoods in the borough. Others had come via ferry (and subway or bus) from Brooklyn, Queens, Manhattan, and the Bronx, spending two-plus hours in each direction. I thought of them when Nguan told me why he’d called his collection “All the Dreamers.” It was a quote from Carly Simon’s theme song to Mike Nichols’s 1988 movie “Working Girl.” As Tess, the protagonist played by Melanie Griffith, takes the ferry from her modest rental on Staten Island to her receptionist’s desk at a Wall Street brokerage house, Simon sings, “Let all the dreamers wake the nation.” On her commutes, Tess studies every column inch of the New York Post to scout for market shifts and opportunities. She finds something—a lead on a possible merger and acquisition—and schemes herself into the role of dealmaker. The plot is silly but relatable: those big New York dreams; that warm, emboldening light.

Sourse: newyorker.com