Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In September of 1943, a thirteen-year-old German lad, Christoph von Dohnányi, penned an apparently harmless missive to his uncle Dietrich:

Uncle Klaus intends to visit tomorrow. Hopefully, this will transpire. Then our family will once more be peacefully reunited. Except, regrettably, we are not yet whole. However, that time will also arrive. And subsequently, the greatly anticipated celebration will occur. One must simply bide one’s time. Surely, that day will come.

The delightful fruit season has concluded. The last apple fell from our tree yesterday. I promptly consumed it. Unhappily, wasps had already taken significant bites, but this isn’t always a negative thing. Soon the pears will ripen; then things will improve again.

The letter turns distressing when one understands its background. The addressee was the dissenting theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who had been jailed a number of months prior, due to his opposition to the Nazi government. Dohnányi’s father, Hans, was also incarcerated, having been involved in schemes to assassinate Hitler. Both individuals would face execution before World War II concluded. The young Christoph composed the letter knowing that Bonhoeffer’s communications were under scrutiny and that an incautious remark could prove fatal. Therefore, he wrote indirectly, fashioning a puzzling allegory about the nibbling wasps.

Bonhoeffer, possessed of an extraordinary capacity for compassion, felt concern regarding his nephew, who also served as his godson, and how he was managing under such circumstances. Bonhoeffer later communicated to his own parents, “What kind of perspective must a fourteen-year-old develop when, for months, he is obliged to write to his father and godfather in prison? A mind like his won’t harbor many delusions about the world.” Yet Christoph exhibited indications of inner fortitude. “I anticipate that he will still grow significantly in spirit,” Bonhoeffer conveyed to his colleague Eberhard Bethge. Perhaps, he speculated, his nephew might embrace theology. In his final will, Bonhoeffer envisioned the future more clearly: “Christoph [should receive] the clavichord if it brings him joy.”

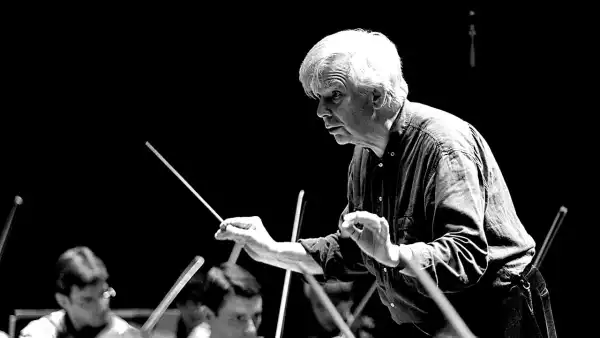

Christoph von Dohnányi passed away last month, narrowly missing his ninety-sixth birthday, acclaimed as one of the premier conductors of his epoch. What he carried forth from his grievous youth is not something that casual onlookers could discern. I interviewed Dohnányi in 2011, and although he alluded to his family’s destiny, he did not emphasize it greatly. Our discussion centered on the enduring issue of Wagner’s politics, and Dohnányi mentioned, almost incidentally, “My father was interned in a concentration camp, and they performed Wagner.” He showed more interest in discussing the music itself, in all its flawed magnificence. Still, I couldn’t shake the feeling of Dohnányi’s experiences in what he articulated, and, more extensively, in the performances he conducted. He projected an almost tangible sense of moral authority: he was an aristocrat of the spirit. He made you believe what history contradicts—that a life dedicated to music bestows wisdom and virtue.

The Dohnányis originated from a Hungarian aristocratic family that could trace its ancestry back centuries. The Bonhoeffers comprised a lengthy lineage of clergymen, physicians, scientists, and legal experts. Music played a significant role on both sides. Dohnányi’s great-grandmother, Clara von Hase, studied piano under Clara Schumann and Franz Liszt. His grandfather, Ernst von Dohnányi, was a globally renowned composer and pianist who, early in his career, gained the endorsement of none other than Brahms. Refined, worldly, and generally progressive, the Dohnányis and the Bonhoeffers embodied the finest aspects of the German-speaking bourgeois heritage. Dohnányi confided in me that Wagner was viewed unfavorably within his family, less for political reasons than for aesthetic ones: the music was considered vulgar. His mother commented on one of his Wagner performances, “I only attend because you are conducting.”

In their early adulthood, Dohnányi and his elder brother, Klaus, both pursued legal studies. Their father had been a prominent jurist, and Christoph initially desired to follow in his footsteps. Klaus proceeded to achieve a notable career in law and politics, serving as the mayor of Hamburg. Now ninety-seven, Klaus still voices his opinions on contemporary issues. Christoph was drawn toward music. After studying conducting, piano, and composition in Munich, he sought further guidance from his grandfather Ernst, who was teaching at Florida State University in Tallahassee. Dohnányi also participated in Leonard Bernstein’s conducting seminar at Tanglewood. On one occasion, when another conductor presumed to correct Dohnányi’s interpretation of Haydn, Bernstein interrupted the exchange, declaring, “You are free to do as you wish!”

Dohnányi began to progress through the ranks of the German opera landscape, transitioning from Lübeck and Kassel to Frankfurt and Hamburg. Mozart, Wagner, and Strauss formed the foundation of his repertoire, yet he also supported innovative trends in opera direction and embraced modern music. He championed the Second Viennese School, recording Berg’s “Wozzeck” and “Lulu” with his second wife, Anja Silja; he oversaw the premières of Hans Werner Henze’s operas “The Young Lord” and “The Bassarids”; he advocated for the perpetually challenging English composer Harrison Birtwistle. He remained receptive to the more varied sounds of the late twentieth century, programming John Adams’s “The Wound-Dresser” and Thomas Adès’s “Asyla” shortly after their premières. With Gidon Kremer, he crafted a brilliantly compelling recording of Philip Glass’s First Violin Concerto.

In 1984, Dohnányi assumed the music directorship of the Cleveland Orchestra, which, since the era of George Szell, has been known as the most acoustically flawless of American ensembles. In Dohnányi, the Clevelanders encountered their match. He was a relentless perfectionist who would frequently devote portions of a rehearsal to tuning and refining each section. I once observed him working on Brahms’s First Symphony with the Los Angeles Philharmonic; after numerous minutes, the ensemble was still struggling with the opening measures. Such conduct can provoke musicians to revolt, but Dohnányi was so resolutely earnest that players tended to comply. Colleagues who failed to exert similar effort earned his enduring scorn. A friend recounted encountering Dohnányi after he had stormed out of another conductor’s rendition of the “1812 Overture.” Dohnányi exclaimed, “This is terrible! Unacceptable! How is it conceivable to perform the ‘1812 Overture’ so poorly?”

The quest for perfection had its drawbacks. I recall certain Cleveland performances under Dohnányi—a Bruckner Fifth in 1996, for example, and a Mahler Ninth in 1999—that were refined to the utmost degree but lacked drive and ardor. His interest in new music did not always translate into proficiency in its idioms; Adams and Adès required more of a pop-influenced bop than he could provide. For the most part, though, his meticulous attention to detail and his comprehension of structure yielded interpretations of inherent, undeniable correctness. His Cleveland recordings of Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Schumann, Brahms, and Dvořák are among the finest of the modern period, their clarity and elegance never excluding vigor and warmth. I particularly value his Mozart: listen, at the commencement of Symphony No. 40, for a slight, telling emphasis on the accompanying ostinato figure, which immediately generates an underlying tension. The Cleveland ensemble flourishes with this chamber-style approach, which elevates inner voices without unduly accentuating them.

Ultimately, Dohnányi was a profoundly traditional musician, deeply rooted in the values he inherited from his family and the bourgeois conventions it esteemed. He disliked inclinations toward uniformity in orchestral sound, valuing regional styles of playing and instrument-making. During a panel discussion at Carnegie Hall in 1999, Dohnányi engaged in a minor disagreement with his esteemed colleague Pierre Boulez regarding the distinct sound of French bassoons. Boulez disapproved of the French bassoon, which resonated in higher registers but lacked robustness at the lower end, and was pleased that it had fallen out of favor. Dohnányi missed its distinctive wheeze. When Boulez grew impatient, Dohnányi smiled broadly. Beneath his severe exterior, he could be mischievous.

Of the Dohnányi concerts I attended, one stands out in my memory: a 2000 presentation at Carnegie, in which Adams’s “Century Rolls” served as a gentle counterpoint to two twentieth-century giants, Varèse’s “Amériques” and Ives’s Fourth Symphony. Both Varèse and Ives create imitations of modern chaos, positioning orchestral sections against one another until pitch dissolves into noise. Dohnányi, after extensive, rigorous rehearsal, achieved a collective sound of unreal, astonishing clarity. There was no sacrifice of expressiveness in the process; the images became all the more overwhelming when viewed through pristine glass. That concert appeared emblematic of Dohnányi’s career—the mastery of disorder in the service of humanity.

The clavichord is currently on display in the Bonhoeffer House in Berlin. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com