Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Brian Seibert

Seibert has covered dance for Goings On since 2002.

You’re reading the Goings On newsletter, a guide to what we’re watching, listening to, and doing this week. Sign up to receive it in your in-box.

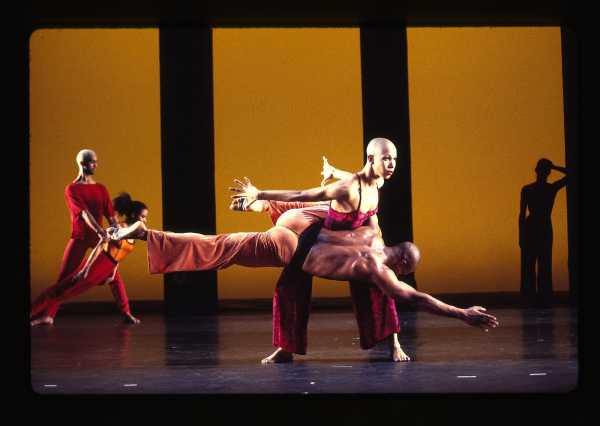

Few, if any, dance performances of the nineties provoked more controversy than “Still/Here,” a multimedia work from 1994 by the choreographer Bill T. Jones, which is now getting a thirtieth-anniversary revival, from the Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company, Oct. 30-Nov. 2, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Most of that controversy began in The New Yorker.

“Still/Here” originated in a series of so-called survivor workshops that Jones, who was publicly H.I.V.-positive, led across the country with volunteers who had faced, or were facing, life-threatening illnesses. From these sessions—during which participants, in verbal and movement exercises, were asked to recall the moments they learned of their diagnoses and to imagine their deaths—Jones took movement material and video testimonials and built them into a work performed by the dance company that he had founded with his romantic and creative partner Arnie Zane (who had died of AIDS in 1988).

Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Company performing “Still/Here” in 1994.Photograph by Dan Rest

Arlene Croce, The New Yorker’s dance critic at the time of “Still/Here” ’s première, wrote about the piece in the magazine, even though she refused to see it. In an essay titled “Discussing the Undiscussable,” she argued that by including dying people in his work Jones had put himself “beyond the reach of criticism.” She called Jones—a MacArthur-winning provocateur who had just been profiled in the magazine by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.—“the John the Baptist of victim art,” the most coercive avatar of a “pathology” that she blamed on the “permissive thinking of the sixties” and a utilitarian bias within the arts bureaucracy. “Parading their wounds,” she wrote, such artists made critics seem expendable. She responded to the piece as to an attack. (Oddly, she later said that she had initially conceived of the essay as a Shouts & Murmurs piece.)

The essay kicked up a storm of commentary that spilled over from the readers’-letters section of the magazine into other publications, with the likes of Tony Kushner, Joyce Carol Oates, Susan Sontag, and Camille Paglia cheering and denouncing its claims and insinuations. Croce’s piece and “Still/Here”—though neither was what fans of Croce or Jones would likely choose as their best work—became infamous together, a conjoined exhibit in the culture wars, bound on syllabi and in cultural memory.

The revival of “Still/Here,” original video intact, offers a chance to revisit that moment, but also to consider the work at a distance from the uproar, in a very different context. How do its juxtapositions of text, movement, and image, of illness and vitality, of death and beauty look today, performed by a new cast of dancers, half of whom weren’t yet born when it was made? Jones is still here; what does “Still/Here” still have to say?

About Town

Art

For some time now, Dietmar Busse has been painting his photographs until the original image nearly disappears, but when he first arrived in New York, in the early nineties, after a childhood in a farming village in Germany, he made mostly small, black-and-white Polaroids. More than a hundred of these, plus some knockout blowups, are included in the sprawling, sensational show “Dietmar Busse Fairy Tales 1991-1999.” Mostly, but never merely, snapshots, Busse’s pictures were taken on bike trips around the city, and the curiosity on both sides of the camera makes them vibrate. There are a number of editorial assignments, including subjects such as Pedro Almodóvar and Ultra Naté, but they can’t really compete with a trio of homely queens at Wigstock or people lounging on Harlem stoops.—Vince Aletti (Amant; through Feb. 16.)

Afropop

For more than four decades, the Beninese French singer-songwriter Angélique Kidjo has been a titanic figure working to dispel the Western myth of “world music.” From the 1991 album “Logozo” to three Grammy-winning LPs—“Eve” (2014), “Sings” (2015), and “Mother Nature” (2021)—Kidjo has fiercely advocated for African music, from Afrobeat to Afropop, jazz, and classical. She is joined on the first U.S. stop of a tour celebrating her forty-year career by the Colour of Noize Orchestra, directed by Derrick Hodge, and the funk ambassador Nile Rodgers, the Chic front man who worked on hits for Diana Ross, David Bowie, Madonna, Beyoncé, and Daft Punk, the last of which earned him the 2014 Grammy for Album of the Year.—Sheldon Pearce (Carnegie Hall; Nov. 2.)

Off Broadway

Alaska Thunderfuck in “Drag: The Musical.”Photograph by Matthew Murphy

Drag, at its best, is a union of glamour and camp, spectacle and heart. “Drag: The Musical”—a tale of two night clubs, written by Tomas Costanza, Justin Andrew Honard, and Ashley Gordon, and directed with pizzazz by Spencer Liff—delivers the goods, with some rock and roll to boot. One club is owned by Kitty Galloway (the “RuPaul’s Drag Race” sensation Alaska Thunderfuck); the other, across the street, belongs to her ex, Alexis Gillmore (a distractingly muscular Nick Adams). But Alexis’s establishment may soon fold because of financial mismanagement, prompting an appeal to her straight accountant brother (Joey McIntyre, bringing his own thunder). He arrives with his young son (Remi Tuckman/Yair Keydar), who discovers—to his father’s consternation and Alexis’s delight—a love of drag. With Jujubee, Jan Sport, and a shit ton of rhinestones.—Dan Stahl (New World Stages; open run.)

Dance

Since being named the resident choreographer at Paul Taylor Dance Company, Lauren Lovette has proved adept at channelling the dancers’ exuberantly warm style and grounded technique. She has provided two new works for the fall, “Chaconne in Winter” and “Recess.” There are other premières as well: Robert Battle, until recently the director of Alvin Ailey, has made a tribute to Carolyn Adams, a beloved former member of the troupe. And there are, of course, the Taylor dances, from the familiar—“Aureole,” “Arden Court,” and “Esplanade,” which turns fifty next year—to the rarely performed, such as “Images,” a dance inspired by the friezes of antiquity, set to Debussy.—Marina Harss (David H. Koch Theatre; Nov. 5-24.)

Art

“Vitrine III” (2024).Art work by Samuel Hindolo / Courtesy the artist / 15 Orient

You can see the thirty-four-year-old painter Samuel Hindolo pushing himself in the two-part exhibition “Eurostar”—made up of photo collages, drawings, and paintings inspired by train-station architecture—not to be identified by one genre. So doing, he avoids a common pitfall: the artist’s commodification and getting stuck in a signature style. Passing intimacies are keenly felt in small paintings such as “Vitrine III” (2024), where the figures are rendered with a kind of awkward grace, a hallmark of Hindolo’s draftsmanship. His faint and subtle renderings of domestic scenes remind one at times of the beginning of Wim Wenders’s “Wings of Desire”—and of the distance and the privilege inherent in privacy being observed, and recorded.—Hilton Als (15 Orient and Galerie Buchholz; through Nov. 9.)

Movies

Edward Berger’s plush thriller “Conclave,” based on a novel by Robert Harris, details a fictional meeting of cardinals at the Vatican, after the death of a Pope, to choose his successor. Ralph Fiennes stars as Cardinal Thomas Lawrence, who is working behind the scenes to prevent the victory of a reactionary (Sergio Castellitto). But an outspoken liberal (Stanley Tucci) has trouble winning votes, and the resulting action involves deft coalition-building and the papal equivalent of October surprises. The drama is clever but stodgy, spotlighting picturesque settings and arcane rituals, and relying on a formidable cast, which also includes John Lithgow and Isabella Rossellini, to invest stock characters with a semblance of life.—Richard Brody (In wide release.)

Pick Three

Sarah Larson on standout podcasts.

1. “The Wonder of Stevie,” bursting with music and hosted with extreme exuberance by Wesley Morris, tells Stevie Wonder’s life story from, roughly, “Fingertips” to “That Girl,” with an emphasis on his five extraordinary albums released from 1972 to 1976. Wonder himself appears in the final episode; peers such as Smokey Robinson tell stories, and musicians and fans including Questlove, Janelle Monáe, and Barack and Michelle Obama (whose Wonder-inspired company, Higher Ground, helped produce) articulate the nature of Wonder’s genius. Also: Barack sings!

2. In “Empire City,” Chenjerai Kumanyika, of the excellent podcasts “Uncivil” and “Seeing White,” provides a bracing history of the N.Y.P.D., the country’s largest police force, beginning with its early connections to slavery and including its history of brutality and overreach. Kumanyika, a warm and shrewd presence, personalizes the narrative with stories about his civil-rights-activist father, who was detained by the N.Y.P.D., and his young daughter, who still believes that police “keep people safe.”

3. Leon Neyfakh and Arielle Pardes’s “Backfired: Attention Deficit,” which follows their previous strong series, “Backfired: The Vaping Wars,” illuminates the complex history of attention-deficit disorder and of stimulant use in the U.S., which began decades ago and skyrocketed during the pandemic, leading to an infamous drug shortage. It’s empathetic and quietly funny; reflecting on Adderall and college, Neyfakh says, “Never in my life have I thought my ideas were better and more original than when I was in the library, high as a kite, tapping out mediocre essays about things I barely understood.”

P.S. Good stuff on the Internet:

- Andrew Garfield reads a Chris Huntington essay

- Tina Brown’s first “Fresh Hell” post

- Pedro Pascal as a mushroom

Sourse: newyorker.com