Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

When David Mamet was planning to bring his 1983 play “Glengarry Glen Ross” to Broadway for a fourth time, he asked Nathan Lane to star in it. Lane agreed, but he had a condition: “The first person you have to hire is Bill Burr.” Lane later had to drop out—Bob Odenkirk took his place in the revival, now running at the Palace—but his casting advice stuck.

Even if you haven’t seen “Glengarry Glen Ross” in a while, you may remember the logline: a few sad-sack real-estate salesmen in Chicago hang around the office, talking their indignant shit. They air profane and petty grievances, and lightly conspiratorial gossip; they lament their insecure place in the bourgeois status hierarchy, and the indignities they endure at the hands of their unfeeling bosses. In “Death of a Salesman,” the long-suffering salesman’s loyal wife is there to remind us that “attention must be paid.” In “Glengarry Glen Ross,” women don’t exist, life is suffering, and loyalty is for marks. The characters are all working men, and they perform both their work and their masculinity with sweaty desperation—two inseparable competitive sports, neither of which they can afford to lose.

“Glengarry” is Burr’s Broadway début. He has appeared in a few movies—he directed and starred in the Netflix movie “Old Dads,” about old dads, and he played a passable J.F.K. in Jerry Seinfeld’s opus about Pop-Tarts—but he is far better known as a standup, having sold out arenas from the Royal Albert Hall to the Odeon of Herodes Atticus, in Athens. He is from outside of Boston, not Chicago, but it’s no mystery why Lane would have associated him with Mamet’s characters. His strangled, squalling voice can make a rant about toasters sound like a cry for help. He has such an unwavering salt-of-the-earth demeanor that he is one of the few comedians who has made it to the upper echelon—he lives in a posh area of Los Angeles, and he flies helicopters for fun—without his act coming across as unrelatable. In an era of left-right polarization, he focusses only on the polarization along another axis: top versus bottom, with Burr aligned pugnaciously with the working man. (And the emphasis sometimes seems to be on “man”: when he sat for an interview with Terry Gross recently, Burr got into an on-air snit about “feminism,” which veered uncomfortably between seeming like a bit and seeming not at all like a bit.) He is fifty-six, with an anti-Trump wife and two young children. As far as I know, he is the only guest who has shouted “Free Luigi!” during a lighthearted late-night interview with Jimmy Kimmel. Burr is a guy with a lifelong anger problem, but—and this is the through line of his past few specials—he’s working on it. “Men aren’t allowed to be sad,” he said in his latest special, “Drop Dead Years.” “We’re allowed to be one of two things: we’re allowed to be mad or fine.” But in fact, he added, “There are a lot of sad men. I realize that now that I know how fucked up I am.”

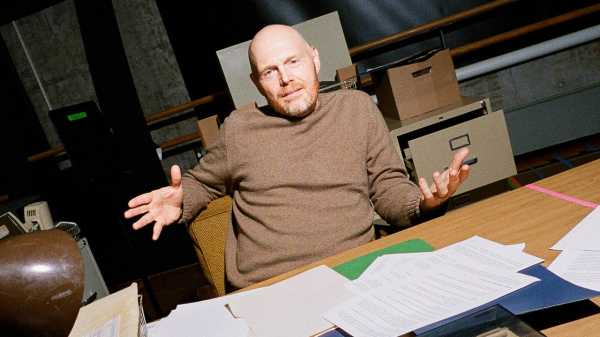

In “Glengarry,” Burr plays Dave Moss, a crotchety salesman who is plotting revenge against the bosses, Murray and Mitch. Some of Moss’s lines now sound dated—some of them sounded dated even in 1983—but his righteous fury at the capitalist rat race (“You find yourself in thrall to someone else. And we enslave ourselves”) requires no updating. For this interview, which has been edited for length and clarity, we met at a coffee shop in Tribeca, where Burr occasionally interrupted himself to quietly mock the outfits of customers waiting in line.

[While you’ve been living in New York, during rehearsals and for the run of the show,] have you spent any time in Brooklyn or Queens?

I went to meet [a friend] for breakfast. I was joking that it was, like, hipster Rodeo Drive. Lululemon—everything was just super corporate, elevated, everyone just trying so hard to find a vibe. I’m not blaming the people. They’ve done this to us. I think one of the ways we deal with the madness—which, I don’t understand why there’s any madness. There’s plenty of food, there’s plenty of money. There’s plenty for everybody. And then these guys who have all of it are screaming, “It’s all going to be taken away.” It’s, like, “Yeah, by you! You guys are the ones taking it away!” It’s not some guy coming over the wall who doesn’t have two nickels in his pocket.

Totally. But, if those guys [the oligarchs] do start messing everything up, then there is really something for normal people to worry about.

Well, there always is. [In politics,] you have to be built a certain way to ascend. It’s reptilian. And one of the most frustrating things is trying to get people to admit that their reptile is a reptile. They just don’t seem to want to do it. They’re, like, “My reptile wears this color tie. My reptile has feelings.” It’s just, like, “No, dude, you have feelings. I have feelings. We need to get on the same page. We’ve got to get rid of the reptiles.”

O.K., we can start there. I want to talk about that. I want to talk about Mamet, too. I saw the play, and there’s a lot in there that deals with this theme—normal people wanting to rise up. What’s the line you have? “Somebody ought to pay”? Or “Somebody should”—

Yes. “Somebody . . . should do something. Something. To pay them back. Someone, someone should hurt them. Murray and Mitch.” That’s what it is. He [Dave Moss, Burr’s character] wants to get these guys back, because it was already a cutthroat business, and then they—you know, it’s sort of like how I feel like these big businesses work. The first thing they do is they get market share, and then they see how much they can get in the market, and then they start screwing their own customers. And then everybody who’s in the company thinks they’re on the bus, and they don’t know that the bus eventually rolls over them.

I think the tone of it is almost as important as the content. I mean this in Mamet, and also in life. It’s one thing to be, like, “You know, we really ought to do something about Murray and Mitch.” And it’s another thing to be, like, “Fuck them. Somebody should make them fucking pay.” Those are different sentiments.

Yeah, that’s a revolution versus just talking in a coffee shop.

[The play is] commenting on the dangers of, basically, lust for money. People always try to just attribute it to capitalism, but I’ve travelled enough of the world—no matter what government is in place, there’s a group of people at the top that are taking way more than anybody else. No form of government, no philosophy, works, it seems, because it’s going to be run by human beings, and we’re inherently flawed. The same way, in my business, you can lose your way. You know, people blow smoke up your ass, you can start to believe it. Start carrying yourself a different way. One of my favorite things to watch is when even your circle of friends becomes a career move. You and I are cool, then I get an inch ahead of you, then I’m looking for the inch-ahead-of-you friends.

Why do people do that?

I don’t do that, so I don’t know.

This business is brutal. When nobody knows who you are, you have this fucking loneliness—laying in bed, going, Oh, my God, am I the guy who doesn’t make it? Then you do get somewhere, and then you have to learn how to handle that. And I find the way to handle it is to disengage with it, try as much as I can to just do what I always did. And I find, if you act normal, people act normal. It’s the law of attraction. If you show up with three S.U.V.s, people want to see who it is.

Not to make everything about the play, but Mamet obviously includes a lot of language about what it means to be masculine, what it means to be a man. [Ricky] Roma keeps building the other guys up by saying things like, “Hey, you’re a man. You’re a real man.”

There’s also that line, “A man is his job.” I don’t know that that’s a thing now. Back in the day—if you joined the armed forces, and you’d say, “I’m a marine”—there’s a pride to that. But, you know, “I’m building an app”? I don’t think you can identify with that. “I’m a creator, I’m a disrupter.” All that reptile talk.

[Laughs.]

I saw a guy today on Instagram—which I’m horribly addicted to. I bottom out, like an alcoholic, and I start reading books again. I’m either on or off. I’m not on it, and I’m reading books, or I’m back on it, and I’m scrolling like a thirteen-year-old girl.

It’s like you said [in one of your specials]: you’ll drink if there’s alcohol in the house. Well, Instagram is always in the house. It’s always in your pocket.

You know how many times I’ve gotten off it? I’m on the phone, I swipe off it, and then I just go right back. Dude, these guys are watching me on my phone like a fucking lab rat. That’s the booze on my shelf now. “I’m just gonna have one. I’m just gonna watch one video.”

The one show I was watching recently, which was incredible, was “Severance.” Ben Stiller. He came out to the play a few nights ago, and I had a funny conversation with him. I go, “Dude, I had to tap out.” He laughs, and he goes, “Why?” I go, “First of all, at one point, I’m watching your show and I’m rooting for somebody’s suicide. Like, ‘Hurry up and hang yourself.’ ” But really it was the episode where this baby was introduced, and—who plays the manager?

Patricia Arquette?

Yeah, when she starts inserting herself in with the baby. I can’t do horror movies where there are kids. I just—if there’s a mom with a kid? Can’t fucking do it.

Talk about “A man is his job.” That show is all about work taking over your identity. When you were saying that, I was thinking, If that’s true anywhere, it’s got to be true of what you do. In standup, it’s very personal. There’s no band name. There’s no hiding behind a guitar. It’s, like, “My act is me, and if I’m not filling up the seats, then that’s a rejection of me.” Right?

I consider what I do to be a job, and my idea of what the purpose of the job is has changed over the years. My thought now is that my job is to—I look at it, like, somebody had a tough week, or somebody had a great week, or they had an all-right week. And it’s my job, no matter what kind of week you had, to make you either forget about it, or make it a better week, because you’re laughing for an hour. That’s why I’m apolitical. My job is just to make fun of things. And one of the things I’m most proud of is that people on the right think I’m a libtard and that my wife writes my jokes, and then people on the left think I’m a Trumper. And the reason for that is that when I go to a red state, I go extra hard making fun of their red guys. And when I go to a blue state, I just go off on liberals. Because, selfishly, that’s a fun thing to do. But I also—say, I’m in a red state, I’m making fun of red people, and then I hear blue people go, “Whoo!” Then I go after them.

What is that?

Growing up without love. That’s what that is. So you just push it away. Any sort of positive “I agree with you” feels gross to me. It has nothing to do with politics, really.

My thing is, I wish we could go back to: If you work forty hours a week, a hundred and sixty hours a month, you can live comfortably. You can pay your rent. I don’t think anybody should be able to argue the fact that if somebody works a hundred and sixty hours a month for you, and they still can’t pay their rent, you’re not paying them enough. And this thing where they then have to go out and get a second job and spend more time away from their children—that’s going to hurt this country. And it’s also an incredibly callous and cold thing to do to somebody, knowing that because you want a bigger pool, they’re going to miss out on the greatest thing ever, which is watching their kid grow up, and you’re stealing those moments away from them. I had a friend of mine, he told me this story. Right out of college, he got a job with this big corporation. He was living in New York. He gets the job. He crushes it. And then they place him in San Francisco. So he got to know somebody in H.R., and they’re having a beer one night. He goes, “You know, I don’t understand. They have offices everywhere. I live in New York. Why did they place me all the way across the country?” The other guy goes, “Ah, they do that on purpose. They want to move you away from all your family and friends so you’re less likely to quit, because you have no options.” And I always just wanted to be in on that meeting, because, you know, they talk around it. Did you ever see—what was that movie that came out a few years ago? “Zone of Interest.” The way that they were talking about putting people in ovens. They were talking about it like it was cargo. And they were dressed nice, and they were clean, and they were having a little coffee, and they were talking about the most evil thing ever. Like, the person who came up with that got rewarded for that. Breaking up families and moving somebody away from—that’s, like, that goes back to slavery. It’s terrible. They’re constantly demonizing the people with no power. Like, the food industry. When they saw heroin addicts, they were jealous of heroin! They go, “I wish people were into our food like that.” So what they call it is, “We want our food to have a certain amount of craveability.” It’s beyond evil, but because it’s legal, and because politicians are so underpaid, and they’re taking the money from that, they don’t do anything.

They’re trying to turn my brain to mush. And I’m helping them every night death-scrolling on Instagram. I need to start reading again.

And then every election, it just comes down to immigration and the other usual five or six talking points. And it’s, like, how did we go through another election and no one was talking about the complete, out-of-control greed? The most amazing thing for me during the pandemic, other than the fact that a virus got politicized, was the fact that if you had a three-hundred-thousand-dollar house, and you were trying to sell it, it was difficult. But if you had a forty-million-dollar house, they couldn’t keep them on the market. I was thinking, Where are they getting this money?

One thing you often hear in blue states is people saying, “What’s with these red-state people voting against their interests? Don’t they know that the Democrats have better policies for them, that they want to give them universal health care and raise the minimum wage?” And one explanation for that is, “Well, the Democrats don’t sound pissed off the way Dave Moss sounds pissed off.” Like, if you’re a person who’s being fucked over—

Well, how about this? How about Democrats haven’t been able to decide who they wanted for their Democratic nomination for three elections? [Bernie] Sanders won it both times, and they said, “Nah.” So, like, why have the primary? They didn’t want him, because he was gonna go after the stuff that’s paying all the corrupt people. And these are liberals! And then you see all this shit that the right-wing people are doing right now, banning books and stuff like that, and liberals are freaking out about that, and it’s, like, you guys were doing that four or five years ago!

You mean with social media?

No, I mean at colleges. They were way overstepping bounds. It’s, like, “Dude, I’m sending my kid there to get an education, not for him to be brainwashed with your extreme ideology, to the left or to the right.” So if you’re on the left, what you feel right now, watching what they’re doing, is how they felt. Now, I’m not saying which is more valid. That’s not my place to make that decision for you. But I feel like most people are in the middle and have been covering their heads for the past twenty years, being, like, “What the fuck?”

If you look at the news, what do they show? When they show a Trumper, they just show the dumbest person they could find, going, “Donald Trump’s a genius. That’s what the ‘J’ stands for.” Right? And then to show a liberal, they show that woman crying when Trump first got elected. That is not an accurate portrayal of either side. Those are crazy people. And then, meanwhile, Democrats and Republicans all got on the same page and agreed that they can’t be tried for insider trading. So, like, what the fuck are we doing here?

One of the most divisive things in this country has been Hollywood award shows. These fucking idiot actors—the way they talk down to red states that they’ve never been to is the exact same way idiot rednecks talk about California. How are you going to get the other side to hear your opinion when you just insult them and don’t listen to them? That’s like people on the right: “What are you, a libtard?” That is the internet. The internet is you start your point off with “Hey, fuckhead.” Who’s listening after “fuckhead”?

The main tension I want to push on here is that it seems like—you said yourself that you have to remain apolitical, because it’s what you do. You have to be able to have the freedom—

But I’m also apolitical because I look at it for what it is.

Sure.

And these guys are just bullshitting me. They’re all bullshitting me.

Sure. But let’s say that, hypothetically, there was more bullshit coming from one side than the other.

More bullshit that you don’t agree with.

Well, O.K. “Don’t agree” is one thing. But there’s a difference—let’s just stay on the example of education. It’s totally true that a lot of universities skew to the left ideologically. But there’s a difference between that and the government arresting you for your speech, or banning a book. Right?

Yeah, but how do you get there? There’s stepping stones. Why is there Fox News? Because there was CNN. All of this shit—no President has been allowed to be President since the first Bush. Once they went after Bill Clinton for lying about a blow job, everybody else—George W. Bush: he stole the election. Obama: he’s not from here. Trump: everything that he did. Joe Biden: “Let’s get something on him. We can’t get something? Oh, his kid does cocaine.” How does it help us if a certain percentage of the President’s day is dealing with the other side trying to take him out and impeach him, which is never gonna happen?

I hear that. But—

Listen. This is my deal. O.K.? These guys who are in power right now, they’re trying to set my people—which is white people—they’re trying to get us back to the mind-set of, like, pre-civil rights. There was a shame, for a while, to being racist, and now there’s a pride to it. And that’s—racism weakens the country. If you wanted to make it a strong country, you would include everyone. And then to watch them taking away these books that explain what my people did . . . first of all, it’s, like, do you think they’re gonna forget? Haven’t we done enough to Black people? Haven’t we done enough to at least just acknowledge what we did? The fact that you’re gonna take that away is just—it’s evil. It’s evil after evil.

So here’s the thing. As a white person, you can’t just be like, “Oh, my God, those red-tie people.” You need to move. You need to do something.

That whole MeToo movement, it started off with something that everybody agreed with. “Hey, we need to get rid of all of these freaks sexually assaulting women and using their position of power for sexual favors.” Who was against that, other than people who were doing it? And then all of a sudden, within two years of that, it morphs into, “I don’t like what you’re saying in your standup act.”

I am careful to assess each thing—what am I getting behind? So what I am behind right now is trying to bring the boiling water down to a simmer. And I would like the rational people on both sides to be running stuff again.

Are we gonna talk about the play, or am I just gonna come off as this political guy?

O.K., let’s talk about the play. Speaking of racism, some of the characters in the play say racist things. “Indians . . . Not my cup of tea.” How does that line go over when you say it?

You’re supposed to—if you laugh at that line, you’re laughing at what an idiot my guy is.

Of course.

But, if you laugh at that the wrong way, I didn’t just change your mind. You came in with that. There was that thing for a while where they were holding comedians “accountable” for what they were saying. Like we were these wizards, like we’d go onstage and say something and then suddenly people thought that. And then, meanwhile, corporate America could be as fucked up as they want to be. So what I would always say to people—I’ll just do it to you. Are you homophobic?

No.

All right. What joke could I tell that would make you homophobic? Is there a joke? How does that joke go?

I mean, I agree with that, up to a point. But I just wrote this piece about how parasocial relationships—

[With visceral disdain]: “Parasocial relationships”? We’re gonna say that now? Is that a sailing term? “Parasocial”?

[Laughs.] You’ve never heard that before?

No! That sounds like some bullshit to censor a comedian, and blame the ills of society on a comedian, rather than the people who actually make the fucking laws. I’m not running a box store. I’m not not hiring people. I’m not trying to fucking poison the food supply.

Sure. The only part that I would push back on is that if you want a bunch of people to listen to you—look, I’m not saying you should be censored. But I—as a journalist, if I say, “I just wrote a bunch of stuff down, you know, whatever, you don’t have to listen to me”—that wouldn’t fly. I have to take responsibility for what I’m saying.

Journalism is not standup comedy. We’re not in the same world.

So what do you think your responsibility is?

My responsibility is to make you laugh. And, if I’m being malicious, people know. People know if you mean it or not. So what people did—you people, you journalists, for a while there, and not even because you gave a fuck, just because it was the hot story—all of a sudden, you’d finish your act, and somebody’d be, like, “I want to talk to you about some of the statements you made.” “Statements? I was up there telling jokes.”

One of the great things about standup comedy is the freedom and the irreverence of it. I’m not saying that it can’t be done in the wrong way. I’m not saying that there’s never been a racist person onstage doing jokes, somebody ignorant. There’s that in every business. But what they were doing is they were using that to try to shape the art form. Liberals were doing that, trying to control the fucking art form. And liberal comedians who sucked were then using that as a way to try to get more clicks and elevate themselves.

I’ve had people who’ve said fucked-up shit about me on the internet, and then they come up to me—“Hey, Bill, how’s your family?” And I want to be, like, “You don’t give a fuck about my family.” But I can’t, because they’re a white woman, so I can’t say anything because, Oh, my God, when a white woman complains, people fucking listen. So I’m just cordial. And those are liberals, dude.

Are we only going to talk about this? Because I don’t want to be like this political-ideology guy.

No, no, that’s fine. [At this point, I tapped the screen of my phone to make sure that it was still recording, and my lock screen lit up: a photo of my two young children.]

That’s life right there, man. You’ve got two kids?

Yep.

What do you got?

Two boys. So far.

Oh, that’s awesome. [Burr lives with his wife and two children in Los Angeles, but during the run of “Glengarry” they’ve spent long stretches of time apart.] That has been the hardest thing about doing this play.

I’ve done a lot of work on myself with all of this alone time. I’ve really been on this mission to get rid of my hair-trigger temper, which, I found out, comes from all the pain in your childhood. So especially with my wife, like, I have a thing that when somebody disagrees with me, I go back to being a helpless child when no one was listening to me. That’s how my brain is wired. And that’s not fair to my wife, because we’re just trying to decide what restaurant to go to.

I’ve had these really deep and sometimes painful conversations, you know, because I don’t like revisiting that stuff. Who does? Who wants to go back and mulch over shit that wasn’t fun? And just because all of this bad stuff is happening right now, this heartless time that we’re in—these robber barons, these new robber barons—that doesn’t mean that you have to give in to that mentality. So I’ve really—I used to be a wallflower, and I’m not now. I’m realizing one of the things that comes with age is this great responsibility to be encouraging and to help out younger people. And I love doing it. It feels good. It gets me out of my own head.

That’s why I stopped watching the corporate news, CNN and Fox, because these people would rather win than be right. They’re just trying to win. They’re not really trying to find the solution. And that was, like, overwhelmingly depressing. So my phone was probably listening to me as I was talking about this, and all of a sudden this thing came across my Instagram feed, because I’m not reading now, and it said that the ancient Greek philosophers had these two mind-sets: there’s philosophia and philonikia. Philosophia is the love of knowledge and growth, or whatever. I get into a disagreement with you—my identity is not my opinions. So I can listen to you, respect you, and I can be swayed if what you’re saying has merit. And then philonikia is the love of victory, which is great if you’re playing sports, but not if you’re, you know, talking to your wife. Like, I don’t know how many times I’ve been in an argument with my wife or somebody, and halfway through it, I realize I’m wrong, and in my head, I’m just thinking, Dude, you’re wrong. You’re wrong. And I just won’t tap out.

But I’m finding, with my wife, that if I just stay in that—“I’m not trying to win anything here. I’m just trying to hear what you’re saying”—and I don’t raise my voice, then she comes back down again. I’ll tell you this: if you actually listen to the woman in your life, it borderline blows their mind.

So I’m trying to live right now in empathy. I have a tremendous amount of empathy for everyone, unless you’re going around hurting people. I don’t care who you are, where you’re from, what your political leanings are, what music you listen to. I don’t give a shit. You’re a fellow-human and I want to vibe with you. I want to find the common ground. I don’t want to get into this arguing shit. That is how they separate you, and then they take these big oversteps. Because these guys right now doing this shit, banning these books—you think they’re gonna stop at these books? We’re going back to the Industrial Revolution now. All of these people died and got their heads kicked in so we could work, and we’re just letting them take it away. They used to have five- and six-year-olds working ten-hour days around machinery, losing fingers and stuff, and they didn’t give a fuck. Those heartless people, they’re the same heartless people today. They don’t care.

I just want to point out that you’re the one who keeps bringing up politics.

I know. I’m trying to be a man of the people. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com