For the most part, Americans have moved past the gender norms idealized by TV moms like June Cleaver from the 1950s sitcom Leave It to Beaver.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, about 1.8 million women exited the workforce, many of them working mothers who left due to childcare issues as schools and daycares closed across the country. Yet, even as women’s employment has bounced back as pandemic disruptions eased and schools returned to in-person schedules, accessing affordable childcare in the U.S. remains a challenge for parents.

For many Americans, childcare costs eclipse mortgage payments and regularly exceed the price of in-state college tuition. It’s a significant chunk of the household budget, and in many cases, these costs force families to weigh the option of one parent pulling back from their job—either partially or completely—to reduce that burden. But who stays home with the kids, and how is that decided?

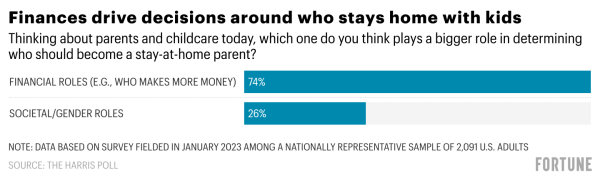

Today, most Americans believe that financial roles play a bigger part in determining which parent should become a stay-at-home parent compared to previous traditional societal and gender roles. Over half (55%) say that it should be the parent making less money who is the stay-at-home parent, according to a recent survey of more than 2,000 U.S. adults conducted by The Harris Poll on behalf of Fortune.

The data shows that most Americans believe these decisions should be driven by what gives families the best chance of success. “That has to be good news,” says Richard Reeves, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and director of the Future of the Middle Class Initiative.

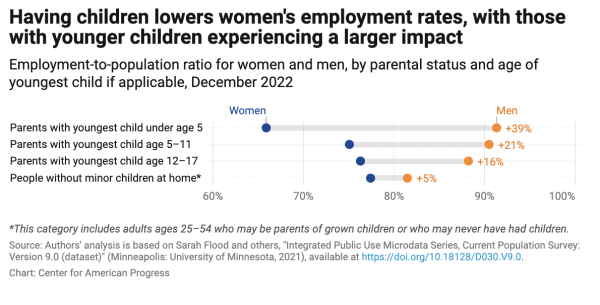

Of course, it’s more complicated than just finances. While Americans’ mindset around gender norms has come a long way, women are still the ones who most often pull back from their careers when they become parents—as opposed to fathers. The research is clear: Having children continues to be a drag on women’s employment rates. That’s due, in large part, to factors such as the ongoing childcare crisis creating scarcity and driving up costs, historical occupation and labor trends, and even the persistent gender pay gap.

The “woefully weak” childcare sector in the U.S., for example, makes the tradeoff between a full-time career and staying home with your children much sharper for parents grappling with questions around work and raising a family, Reeves tells Fortune. “If you want to feel good about the care your kids are getting while you’re in the labor market, that requires significantly more…investment and more of a focus on care itself,” he says.

Headwinds like these lead many mothers (typically white, middle and upper class women married to men) to question the value of their continued labor force participation—far more than fathers. Yet there’s evidence that this too is shifting. While mothers’ choices around working and staying home have always been complex, they are perhaps even more so now in the era of hybrid work and a growing societal reset around work/life balance.

“There’s a deeper set of questions now being asked about the relationship between family and work than perhaps there was in the past,” Reeves says. There are always going to be tradeoffs between work and child-rearing, but with the right policy changes and more support, perhaps the sacrifices don’t have to be as dramatic for women.

Why are women still more likely to be stay-at-home parents?

Today, more than three-quarters of prime-age women (those ages 25–54) are currently holding down a job. That’s a slightly higher rate than the roughly two-thirds of women who were working a decade ago, according to recent analysis from the Center for American Progress. And about 84% of women in the workforce today are working full time.

Yet when it comes to family dynamics and finances, women in hetrosexual marriages are still at a slight disadvantage than their spouses. Less than half of mothers (47%) are the primary breadwinners and earn more than half of the household income, according to Motherly’s 2022 State of Motherhood report.

While some of that is arguably tied to the gender pay gap, relationship dynamics also have an impact, Reeves says. Even as the average age of marriage has gone up and women are having children later, the gap in the age between male and female spouses hasn’t changed much—usually around two to three years’ age difference. So it is still the case that fathers are typically older than mothers, meaning they tend to be slightly further in their careers and have a greater chance of earning higher salaries.

“Everything else equal, age is a very strong predictor of earnings,” Reeves points out. “So the gender pay gap within couples is not the same as the gender pay gap across the economy.” When comparing two salaries to decide who stays home with the kids, men often have the upper hand.

“I like to think that people make decisions in consultation with others in their households and that they are doing some dynamic joint optimization,” says Claudia Goldin, a Harvard economist and expert on the female labor force. “But women haven’t always been powerful bargainers in their homes. They have worked to protect their children and others, not always themselves.”

In many cases, there may not be a true “stay-at-home” parent, but there’s likely an “on-call-at-home parent,” Goldin says. There can be two lawyers married with children, or doctors or teachers—but one of them will likely be the “on-call-at-home” parent who takes a position that offers more flexibility but lower pay. Typically, it’s the woman in that role—and that accounts for a lot of the gender pay gap, Goldin says.

Personal traditions and belief systems do still matter, she adds. If both parents make about the same amount, Harris finds that nearly half of Americans (46%) believe it should be the mother who stays home with the kids. Of course more men (52%) than women (41%) agree with that sentiment—which is driven, in part, by the fact that over half of Americans believe it’s more beneficial for children to have their mothers be the stay-at-home parent rather than fathers. Again, though, this is a more common belief among men (61%) than women (49%).

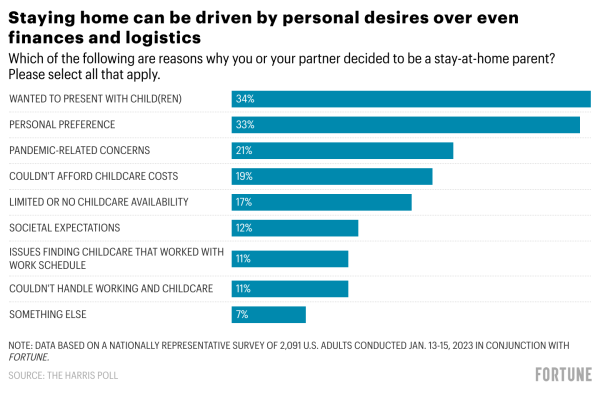

But it is true that among current and former stay-at-home mothers, personal desires—more than finances and logistics—ultimately drove the decision, according to the Harris survey. A full 34% of current and former stay-at-home mothers cited trust factors—not trusting strangers to watch their children—as a reason they opted out of the workforce. And that’s not a one-time finding. More than half of working mothers (59%) are dissatisfied with their childcare situation, Motherly found.

It’s true that more mothers want to be at-home parents with young children than dads do. There are some biological reasons, such as breastfeeding, that may make it more appealing for moms to stay at home when their children are young, Reeves says.

But that doesn’t mean mothers want to do a greater share of parenting forever, Reeves says. What mothers don’t think generally is that 12 years later, they should still be the only ones coordinating their child’s dentist appointments. Even those women who want to step back from the workforce for a period still want an “equality of effort” when it comes to raising their kids, Reeves says.

Repercussions for the workplace

For most people, work is essential. It not only provides financial security and promotes social equality, it also helps ensure a sustainable economy for all. But the typical tradeoffs for women between work and caregiving duties jeopardize that, especially in the face of the childcare crisis.

About 12.3 million children in the U.S. have working parents, but there’s only about 8.7 million licensed childcare slots available, according to a recent Child Care Aware of America report. That leaves a potential gap of about 3.6 million children needing spots that simply don’t exist.

And that doesn’t even take into account the quality issues many parents face in finding childcare they’re comfortable with. If you’re at work, and you’re worried about your kids because you’re not quite sure about the environment they’re in, that’s going to have an impact—not just on individual performance but on productivity overall.

That has real-world implications for the economy and the workforce. Research shows the lack of adequate childcare for infants and young children across the country is estimated to cost the U.S. $122 billion annually in lost earnings, productivity, and revenue.

Employers are losing $23 billion annually in the form of reduced revenues and inflated recruiting costs to replace parents, particularly, leaving jobs. Those costs have risen steadily from the $12.7 billion reported in 2018. That lack of childcare not only suppresses workforce productivity, but it keeps many parents out of the workforce and drives up competition for new hires—not to mention increasing turnover as working parents look for better alternatives. A company can spend $30,000 to $45,000 in recruiting and training costs when trying to replace an employee earning $60,000 annually.

Nearly half of working mothers (48%) report they’re disappointed in their employer’s lack of schedule flexibility and paid time off policies, according to Motherly’s findings. Perhaps more concerning, last year 23% of working moms reported they don’t believe it’s possible to successfully combine a career and motherhood—up from 17% in 2021. That leaves many either staying out of the workforce or contemplating leaving their job, neither of which is good news for employers or the wider economy.

“There are two forces at play: people on the sidelines and a need for talent,” says Libby Rodney, futurist and chief strategy officer at The Harris Poll. Smart companies, she says, will recognize the potential of working mothers and those returning to the workforce, and build bridges to meet today’s talent where it is and offer flexible solutions that adapt to real-life parenting needs.

Employers are making some progress. Despite nearly half of employers planning to trim benefits this year amid the uncertain economic climate, 46% of companies are prioritizing childcare more in 2023, according to Care.com’s recent Future of Benefits Report.

There’s a “deeper reckoning” happening right now around work versus family

When it comes to leaving the workforce, the mothers who pay the highest price for being out of the labor market tend to be the ones with the highest education and the highest earnings potential.

“The opportunity cost of being out is really high,” Reeves says. Taking time out of the labor market does hurt women’s earnings—more than it should, he adds. In fact, the lifetime estimated losses associated with the the so-called “motherhood penalty” can range from $161,000 to $600,000, according to the Women’s Institute for a Secure Retirement.

Of course, it’s a luxury, in some ways, for women to make the choice to step away from the workforce to care for their children—probably because their partner is financially stable or they have enough savings or wealth to make it work. Single mothers typically don’t have the option to stop working because of expensive or less-accessible childcare.

But thanks, in part, to the pandemic, the stark all-or-nothing choices mothers have faced around working or not are becoming more flexible. Certainly the pushback among women around the idea of “having it all” began long before the pandemic, but the global outbreak helped showcase how different working models are possible—and even productive.

“The pandemic was like an accelerant to that process by essentially just completely upending the rules in the structures of daily life and of the economy,” Reeves says. “There’s a deeper reckoning going on here.”

Rather than thinking about whether they should be a full-time, stay-at-home mom, many women are approaching the challenge of balancing their family and career ambitions by questioning the optimal configuration of adult work hours, says Emily Oster, an economist and professor at Brown University, as well as the author of a twice-weekly newsletter, ParentData, focused on on pregnancy and parenting.

There’s been a shift away from workers simply accepting what Goldin coined “greedy work,” the types of jobs that suck up all of a workers’ time. “It’s become more possible to work part-time or to work remotely; to have versions of a job that fit better with the kinds of parenting or the other sort of family constraints that people have,” Oster says. And Goldin agrees, though it does vary by industry. “The more educated work at home more now, do less commuting, have moved farther from their offices,” she points out.

Reducing the sharpness of the tradeoff between work and child rearing responsibilities is the goal, Reeves says. “One way to do that is through paid leave policies, etc, to changes in labor market institutions, career trajectories, but also by ensuring that there is access to high-quality childcare, because then the trade off between working and making sure your kids are okay is not as great.”

It’s worth getting to a place where women are not feeling forced to leave the workforce, but rather if they do, it’s because of an active choice—and one that may not entail leaving completely, Reeves says.

“What we need is a continued revisiting of taking gender a little bit more out of the equation,” Oster says. “You know, dads can stay home, too.” And in fact, 63% of Americans surveyed by The Harris Poll believe dads will be more likely to become stay-at-home parents in the future.