Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The bond between Adebunmi Gbadebo and her chosen medium, earthenware, is a kind of plea—originating from Gbadebo herself. Those religiously inclined might view a ceramicist as a kind of absolute ruler; they may discover a painful kinship with the notion of clay as the modest, inarticulate substance of existence from which they are formed. But earthenware will express its defiance. Under certain conditions, earthenware will opt for devastation. Gbadebo keenly desires to retain earthenware in a nearly unreal state, a condition of near animation, a hardened stubbornness, so that it can convey to us, manifested on the pedestal, what it is contemplating.

Gbadebo undertakes, periodically, a journey. She travels from her workshop in Philadelphia to True Blue Cemetery, a final resting place for the enslaved and their progeny, situated in Fort Motte, South Carolina. The graveyard derives its title from the adjacent plantation, True Blue; the plantation, conversely, acquired its moniker from its premium product: indigo dye. The concentration of iron within the bedrock of this locale is insufficient for the manufacture of steel, but it suffices to give the earth a reddish-brown hue. Gbadebo manually excavates the earth, amassing tubs upon tubs, totaling approximately eight hundred pounds, which she transports back to her studio, where she filters out debris, integrates water and supplementary clays, and then blends it into workable earthenware. Subsequently, she molds the earthenware into containers of assorted oval forms, stout shapes roughly eighteen inches in breadth that might resemble baskets, the human pelvis, and/or nascent seeds at the precipitous moment of disintegration. Gbadebo subjects her containers to two firings, some undergoing a variant of the Japanese raku procedure in which the initial firing typically reaches approximately eighteen hundred degrees, and the second, around a thousand degrees. At this juncture, the containers are removed. They undergo the duress of a remarkable plunge in temperature, succeeded by the incorporation of heated sawdust, strands of hair, and saccharine—which Gbadebo elucidated to me, recently, as a “final entombment.” The domain of demise. The carbon element in the combustibles infuses itself into the surface of the ceramics, resulting in expanses of black, modulations that Gbadebo can manipulate only to a limited degree. The containers, having imparted their enigmatic communication, are designated namesakes for the individuals interred at red-earth plantations. “Ellis Sanders,” “John Ricen Ravenell,” “Maum Hannah”: these appellations pertain to Gbadebo’s forebears. She gained insight into them through researching the testament of a South Carolina slave owner. In recent times, she portrayed herself to me as someone in mourning.

I was unaware of Gbadebo’s lineage when I attended her introductory solo exhibition, “Watch Out for the Ghosts” (an allusion to Amiri Baraka’s celebrated poem “Why’s/Wise”), at the Nicola Vassell Gallery, earlier this September. Nevertheless, I discerned a disquiet within the ambiance that lingered extensively afterward and eventually solidified into something firm and authentic. The enduring impression of the exhibition was a sensation of . . . being jabbed. Feelings crawled up the arm. Tactility is the secondary sense within the gallery context, evoked, at this display, by virtue of Gbadebo’s surfaces. Yet, the spectral sensation requires a moment to register. From a distance, the interpretation stems from the visual sense, which finds delight in the expansive openings, the undulations at the base that reverently evoke the tradition of honoring the female physique. The containers, perched upon teal platforms, beckon as ageless artifacts. However, as one approaches, the concentration of energy transitions from configuration to “integument” and vacant space. This constitutes an entirely distinct drama. Gbadebo fills, for instance, a container that conjures a fertility devotional sculpture with heaps of grain. The appealing wide orifice now appears, upon closer scrutiny, as a bottomless cavity, the grain akin to larvae, reproducing incessantly. Elsewhere, Gbadebo distinguishes the grains, imbedding them within the containers’ exterior layer, so they stand upright and protruding. In another piece, they jut outward like incisors. Additional organic substances are enlisting in her composite-media art, her exploration of a proscription against what constitutes “material”; human tresses, equine hair, pine needles, seeds, animal skeletons, cherry-tree branches. Thus, in a manner, within this chamber, funerary vessels are vibrant—history exists.

Gbadebo is thirty-three years old. She was born to an African-American mother and a Nigerian father, and brought up in Maplewood, New Jersey. During her art education, she held little regard for Eurocentric painting analyses, which she perceived as imposed upon her. She requires space, heaviness, and three-dimensionality. And vitality. There exists the perception that Gbadebo, who is also a Yoruba priestess, senses depletion amidst the non-essential. Her initial materials encompassed hair, which she procured from barbershops or distant benefactors. (Her website features an address for hair contributions.) Following the revelation of her maternal lineage’s burial site, subsequent to her mother’s passing, Gbadebo broadened her materials to incorporate the outcomes of slavery’s enterprise—rice, cotton, and indigo. Her supplementary medium is paper, amendments to the rigid ledgers of capital-H history, fashioned from earthenware, plantation soil, and cotton pulp, and tinctures utilizing liquefied earth and indigo. All of her creations bear the imprint of their genesis. It invariably seems as though the artist has just departed.

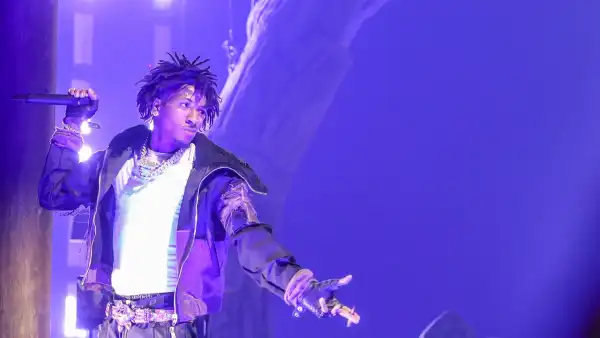

“Glory (A Taste of Sweetness after Near Death)” (2001).Photograph by Greg Carideo / Collection of Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg / Courtesy Bronx Museum

During my conversation with Gbadebo, it occurred to me that I was denominating her a sculptor or a ceramic artist interchangeably. Which designation held accuracy? Correctness was the crux. “I believe I more closely relate to the notion that I am a sculptor, although I welcome all labels, yet this embodies sculptural creation,” she conveyed to me.

Earthware provokes us. The inauguration of a pottery exhibition virtually necessitates a preemptive maneuver against enduring biases concerning the medium within the art sphere. Pottery has historically endured disparagement as trivial, domestic, feminine, and biblically overused—a utilitarian craft, subordinate in the hierarchy of artistic creation to the masculinized domain of sculpture. The California Clay Movement of the nineteen-sixties, spearheaded by Peter Voulkos, is widely regarded as the pivotal juncture in pottery’s standing—the Abstract Expressionist transformation for the medium in need of elevation. The 1981 Whitney Show commemorating Voulkos, Kenneth Price, and others is entitled “Ceramic Sculpture: Six Artists,” which is somewhat akin to labeling a display “Bronze Sculpture: Six Artists.” Does the earliness of pottery in human history, furthermore, bear connotations of the pre-civilized Hobbesian state, even predating stone sculpture on particular continents? The traditional affiliation of pottery with the art of the underclass seems a contributing factor, as well. Denigrations against practicality, the grievance of a twentieth-century art realm swayed by Dada. At the Met, circa 2023, “Hear Me Now: The Black Potters of Old Edgefield, South Carolina,” the astonishing artworks of David Drake, an artisan from the mid-nineteenth century, were showcased alongside containers by contemporary artists encompassing Simone Leigh, Woody De Othello, and Gbadebo—a means of integrating Drake into the role of ancestor. However, Drake, who produced numerous of his sublime and formidable pieces while enslaved, recognized his own artistic identity. Variations of “I made this pot” are eternally etched onto his containers.

This season presents an opportune moment to contemplate the enigmas of earthenware. At the Bronx Museum, an exhibit titled “Ministry” exhibits upon altar-resembling platforms the miniatures of the Reverend Joyce McDonald, spun by hand. McDonald crafts exquisite and impactful busts that possess the essence of religious reliquaries, portraying episodes from her existence, or existences; McDonald unearthed her artistic talent in an art-therapy curriculum subsequent to her H.I.V. diagnosis. Within the exhibition catalog, Kyle Croft, the curator, references a mentor’s employment of the Lazarus allegory to explicate McDonald’s sensation of regeneration. (That saint, subsequent to resurrection, quipped upon witnessing a boy pilfer a clay vessel: “The earthware purloins the earthware.”) Additionally, at the Ford Foundation, Gbadebo’s oeuvre is once more presented, within the exhibit “Body Vessel Clay: Black Women, Ceramics, & Contemporary Art,” alongside Simone Leigh, Phoebe Collings-James, and other contemporaries. Curated by Dr. Jarah Das, a researcher in clay and its connection to the body, the display articulates a revitalizing declaration regarding a parallel movement in clay, centered not upon Voulkos but upon the Nigerian potter Ladi Dosei Kwali, a masterful alchemist of Gbari design and British studio technique. Akin to Kwali, or perhaps emulating Kwali, Gbadebo employs a coiling methodology, maneuvering her own physique in relation to the clay, as opposed to remaining stationary while the clay whirls repeatedly. Considering the origins of the earthenware, Gbadebo is rotating her own essence. ♦

An earlier iteration of this article misidentified the operators of True Blue Plantation and the slave owner whose will Gbadebo researched, and misstated the burial site for some of Gbadebo’s ancestors.

Sourse: newyorker.com