Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

He sits squarely in front of us on the screen, a full-bodied man with a carefully trimmed white beard and a nearly bald head, his eyes looming behind dark-framed glasses—one eye glaring with cyclopean fury, the other with lid at half-mast, as if signalling a secret of some sort. Behind and around him stand solid walls of CDs—perhaps a hundred thousand disks—and sometimes, depending on where he is sitting in his house, a bronze tam-tam. He speaks rapidly, voluminously, with growling dips into the lower register and high-pitched flights of indignation or rapture. He tends to be smiling, and sings (often) in a scratchy voice redolent of old Yiddish songs and Hebrew chants. He is merry, outraged, laudatory, abusive. If Dickens had set about creating an improbable YouTube star—a classical-music-record critic—even he might not have come up with anyone as vivid as David Hurwitz.

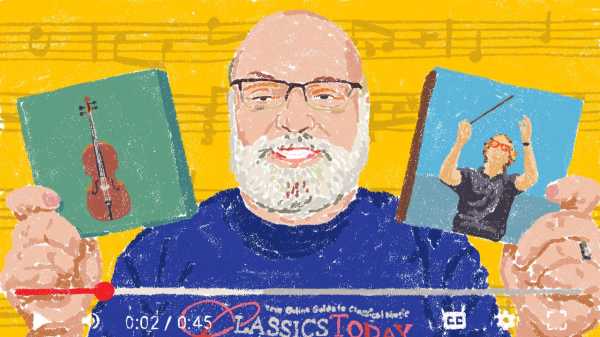

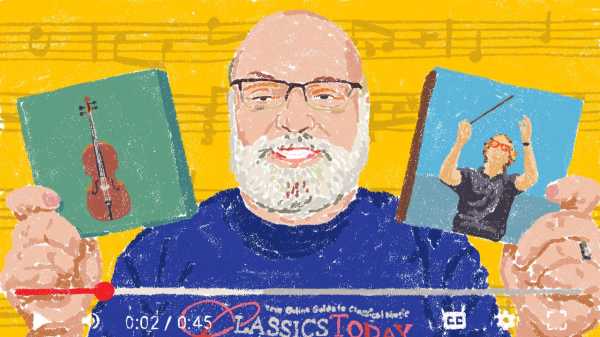

Hurwitz is the executive editor of the online classical-music magazine ClassicsToday. Founded in 1999, the website publishes reviews of new releases, re-releases, books, and concerts; articles on aspects of the recording business and the classical repertoire; and Hurwitz’s diatribes and panegyrics. It also features links to his videos, which he began filming for the site in 2020, during lockdown. Averaging three a day, he has by now made more than four thousand, each one lasting anywhere between six minutes and an hour. ClassicsToday is partially paywalled but anyone can watch the videos, and last year Hurwitz’s YouTube channel received almost ten million visits.

The setup that Hurwitz uses is not excessively complicated. He sits at home in front of a MacBook, opens Photo Booth, and talks. He offers opinions of recordings and musicians, bits of music history, and analyses of specific works. (For instance, he has talked about the slow movement of Beethoven’s “Pastoral” Symphony—“the scene by the brook”—and the tendency of some conductors to take it too slowly, thereby killing the entire work.) He will make silly jokes, acting the buffoon in an ironic assault on clichés and pomposity, and twit the conservatism of orchestra programmers by making up his own ideal programs. Many of his opinions are unorthodox and expressed with a freewheeling exuberance generally unknown in a profession—classical-music criticism—that is normally self-effacing and respectful, if not carpet-slipper timid and dull.

Hurwitz has written sixteen books about music (among them “Beethoven’s Orchestra Music: An Owner’s Manual”), and he can be scholarly and exhaustive, devoting separate videos to each of Haydn’s hundred and four symphonies (he is now up to No. 74). But in judging a recording he thinks particularly bad, he may simply say, “It sucks.” Now and then, grinning with the excitement of the kill, he dons what he calls “the white scarf of irredeemable chutzpah”—an actual white scarf—to bestow an “Avoid Like Death Award.” (A recent winner was a Sony box set of Bruckner’s symphonies, with the Vienna Philharmonic led by the German star conductor Christian Thielemann—“a terrible conductor except in a few operas.”) “Lots of people think criticism should be mild, genteel, and as refined as the art of music itself,” he told me, when I paid a visit to his home. “I say, ‘Take a pill and try to acquire a sense of humor.’ Satire and caricature are vital elements of criticism as well as comedy.”

For someone stumbling into one of Hurwitz’s videos, the importance attached to in-the-weeds details might seem baffling: such-and-such a pianist’s Chopin performance is good but not as good as his performance twenty years earlier. Yet it’s equally possible for the uninitiated to be pulled in by the chatter and grade-giving, much as people get hooked on a sportscaster rattling off a player’s old statistics. Who knew that it was possible to talk in this educated but roughhouse way about Mozart, star sopranos, Herbert von Karajan? Or that the fate of the world—or at least the fate of pleasure—hangs on whether string players warm their tone with vibrato? For those to whom such things matter at all, they matter desperately.

“Hello, friends,” Hurwitz’s webcasts almost always begin, and that breezy assumption of friendship is fundamental to his style. He assumes that we are interested, speaking at once both to experienced collectors and to digital-age beginners (who may need to hear, very gently, that the movement of a symphony is not a “song”). His commentary is equally free of snobbery and of attempts to dumb anything down. It’s apparent from just minutes of a Hurwitz spiel that he’s a performer. When I told him as much at our first meeting, the obvious remark seemed nevertheless to please him a great deal. “It has to be a performance,” he said. He spoke in a quiet, even tone that was very different from his expostulating Jewish-Falstaff mode on camera. That voice, the YouTube one, takes a little getting used to, but once you hear it three or four times, it’s very hard to get it out of your head.

Hurwitz is not obsessed with the live performances that absorb most critics. His obsession is with the innumerable recordings that have been issued in the past seventy-five years or so—a glorious panoply of changing musical taste that reflects the interplay of art and commerce in the most productive and wasteful culture the world has ever known.

The current era of classical music within capitalism begins in 1948, when Columbia Records introduced its version of the long-playing record, a wondrous affair of notched microgrooves pressed into a form of plastic—the immortal vinyl. One of the new records could play as much as forty-five minutes, and in decent sound, too, a technological miracle that worked particularly well for classical music, whose noblest invention, the symphony, generally lasted from twenty to forty-five minutes (some monster cases by Bruckner, Mahler, and others notwithstanding). You could get two Mozart symphonies on an LP, or all of Beethoven’s “Eroica,” or, on two LPs, Beethoven’s Ninth.

In the nineteen-fifties, much of the standard repertory was recorded in monophonic sound. But stereophonic sound, thrillingly detailed in its re-creation of spatial depth, took hold at the end of the decade, and essentially the entire standard repertory was rerecorded. Wilhelm Kempff, having recorded the complete Beethoven piano sonatas in the fifties, recorded them again in stereo in the sixties. Consumers’ hunger for better sound created enormous cash flow for record companies.

And then it happened all over again. The digital revolution of the early eighties prompted the record companies and their stables of conductors, orchestras, soloists, and opera singers to redo the entire repertory once more. (The late pianist Alfred Brendel, having recorded all the Beethoven sonatas in analog sound twice, went back to the studio to produce a digitally recorded set.) It was a boom time for recorded classical music. CDs were cheap to produce, and companies could afford to put out disks of obscure, sometimes previously unrecorded repertoire. Digital techniques could clean up the scratchy sound of great performances from the nineteen-twenties and thirties, putting record companies sometimes in competition with their own backlists. The results of all this hyper-production are both glorious and appalling. Well over a hundred sets of the Beethoven symphonies are now available. Who needs another? Or a new set of the Brahms symphonies? You can already choose among Brahms recordings by Furtwängler, Toscanini, Walter, Jochum, Klemperer, Karajan, Levine, Abbado, Chailly, Rattle, Mackerras—to name just some of the famous conductors tackling these works.

Today, lovers of classical recordings find themselves in a precarious moment. Yes, most of the classical catalogue is still accessible, whether on streaming services, on Amazon, in used-record stores, or, in a scattershot way, on YouTube. But the commercial viability of classical, long tenuous, is fading further. FM classical broadcasting is a shadow of what it once was. CDs are vanishing—vinyl LPs now sell more copies per year. At this point, the major labels are practically giving away disks, throwing them into large boxes, sometimes with lavish notes and photos, sometimes with contemptuous bareness. Who knows how long this plenitude will last? The business could drown in its own blessed superfluity. Capitalism, which generously expanded classical recording, could abruptly squeeze it, even destroy it. The competing streaming sites could contract, combine, or vanish overnight.

Meanwhile, the cultural visibility of this incomparable art has been diminishing for years, at least in this country. Every sizable American city has its symphony orchestra, but will this always be true? Music education—apart from band practice—has been vanishing from public schools. (In some areas of Asia, courses in Western music are mandatory.) The enormous record stores—Tower, Virgin, FYE—with their endless rows of operas and concertos, have largely disappeared. It’s almost impossible to imagine a time in which a classical musician might be on the cover of Time magazine, as Bernstein, Arthur Rubinstein, Shostakovich, and a host of others all were. Ignorance of classical music, for many people, is no longer something to be ashamed of, as it was sixty or seventy years ago. If you are indifferent to it, no one will notice; if you hate it, you may even be praised for your lack of snobbery. Almost no one will be so gauche as to tell you that you are missing out on something that could change your life.

Hurwitz, however, is undaunted by such matters. For one thing, he is not troubled by the notion that children will be lost to classical forever if they are not turned on to it early. “To hell with young people,” he told me. “Classical music has traditionally been the preserve of older listeners who have time and disposable income, and that is my audience. Well, O.K., it would be hypocritical of me to disregard young people entirely. I’ve been a classical-music junkie since I was six, so there are certainly young listeners. But what I dislike is the notion that performing-arts organizations should spend their time and energy trying to attract a young audience by making the product ‘hip’ and ‘relevant’ when the population that is most receptive gets ignored. And there will always be old people.”

It’s also true that, if the business is always dying, parts of it always seem to be springing back to life. In recent years, new boutique labels offering unusual repertory have found a niche in the marketplace. Technological advances have made it far easier and cheaper to make a high-quality recording, and the astoundingly high standard of contemporary performance means that a recent live recording can easily rival one of fifty years ago that might have taken three days of studio sessions. A few of the great orchestras, including the London and Chicago Symphonies, have been issuing records and concert broadcasts on their own. The Berlin Philharmonic has a “Digital Concert Hall,” which offers access to both live-streamed performances and an enormous archive of videos going back to the early nineties.

“The stuff keeps coming,” Hurwitz exulted in one of his videos, “and there’s no sign of its stopping.” The problem is keeping the audience alive to it.

Hurwitz’s house, near New Haven, doesn’t appear particularly large from the outside, but when one is inside the place seems to expand, like a child’s dream of a candy store, with room after room of goodies. You pass through a small kitchen and living room (life is clearly elsewhere) and then into a CD-thronged enclave. CDs, some of them in boxes so large they could serve as furniture, appear in the laundry room, in the bedroom, and in a large basement space, the “overflow room.” After renovations that enlarged that space and added shelving on three sides, the overflow room became the always-flowing room, one of the sets for Hurwitz’s videos. Though many shelves are stacked with disks two rows deep, Hurwitz told me, “I pretty much know where everything is.” In the guest room, there are complete scores of Shostakovich’s works, the critical edition of Verdi’s operas, and books of music history and criticism. Hurwitz shares the home with his partner and two enormous cats, who assault many oddly shaped scratching posts placed around the house to keep them from jumping into Dave’s lap when he’s holding forth—or singing, as he often does, in a heimish but accurate interpretation of the music under discussion.

The singing, it turns out, is a consequence of the major labels’ attitudes about copyright. Hurwitz plays excerpts of recordings put out by the independent labels Naxos, which is based in Hong Kong, and Supraphon, which is Czech, but not from the major labels—Universal Music Group, Sony Classical, Warner Classics—which track the use of their music on YouTube and charge creators for playing time. “Aren’t they acting against their own interests?” I asked. His smile vanished. “Large corporations,” he insisted, “are obsessed with preserving the rights of pop-music artists who make them money, and their legal departments adopt a one-size-fits-all approach to protect popular music. They don’t care about classical music at all, and there is no discussing it with them that I have yet found. So I sing.”

Hurwitz’s love for the best performances began when he was six. He was born in Wilmington, Delaware, in 1961, and grew up in Connecticut. As a child, he played various instruments, though none very well. (The tam-tam often seen behind him was loudly struck in community orchestras.) He learned to read music, and he was blessed with a good memory. He earned an M.A. in history from both Johns Hopkins and Stanford, but he does not have an advanced degree in music. After graduation, he worked in the real-estate division of a bank, and he still has a full-time day job in finance. All the while, he has published articles on performance practice in academic journals, pursuing the life of an independent scholar.

By his twenty-fifth birthday, he had finished a book called “Beethoven or Bust: A Practical Guide to Understanding and Listening to Great Music.” The tone is learned but casual. He began writing criticism for audio- and record-review magazines in 1986 and has never stopped. Nowadays, on ClassicsToday, he leads a cohort of critics, including Jed Distler and Robert Levine.

“An insatiable interest in everything to do with music”—that’s what Hurwitz said is necessary to be a critic. “And, second, a healthy dose of insecurity that pushes you to learn all that you can.” Julia Child, he said, was his model for how to address an audience: “Be direct, be honest, have a sense of humor, nobody’s perfect. It’s O.K. to make mistakes now and then.”

If the entire business is not to collapse, dramatizing the best work may be one way of keeping it alive—a way of keeping new interpretations alive, too. And Hurwitz excels at exhortation. Unlike earlier critics, he brazenly turns judgment into competitive play, punching up his discussions with show-business savvy and gamesmanship. What is the best recording of Stravinsky’s “Petrushka”? Why aren’t more people listening to Honegger’s great Third Symphony or Mendelssohn’s intense Sixth Quartet? He will introduce a piece, tell some stories about its performance history, talk (sometimes) about the intricacy of its structure, clown around, perhaps curse the British musical press, which he hates, and then, holding the disks in his hand, he will evaluate a dozen or more candidates. The best Beethoven’s Seventh? The suspense mounts. The best, he says, is George Szell’s performance with the Cleveland Orchestra, from 1959. “Absolutely not!” says this classical nut, but Hurwitz doesn’t mind; he enjoys disagreement, since the love of music flourishes in an atmosphere of passionate attachments and strong distastes.

How do you talk publicly about classical music without making a fool of yourself? No one was more aware of this difficulty than Leonard Bernstein. In a 1957 article in The Atlantic Monthly, Bernstein, echoing the critic Virgil Thomson, deplored the “music appreciation racket”—the mass of commentary, exposition, persuasion, and seduction that flourished until the sixties, in schools, on the radio, and in book after book, much of it dull or embarrassing. In some ways, however, I mourn its passing. At least kids knew something of Bach and Mozart—or played a little of it—before they graduated from high school.

Indeed, I am a product of “music appreciation” myself. Journeying every week to the old Donnell Library, on Fifty-third Street, I would return two scuffed LPs (Beethoven conducted by Toscanini, say) and take out two new ones (Mozart conducted by Beecham). I might also take out a book by Sigmund Spaeth, a man who, for decades, was a rolling mill of classical-music evangelism, in such works as “The Common Sense of Music” (1924), “The Art of Enjoying Music” (1933), and “Great Symphonies: How to Recognize and Remember Them” (1936). In this last, Spaeth, again and again, prints several bars of a symphony with words strung below the notes to help children remember the tune. Thus the gentle repeated two-note pattern with which Brahms begins his Fourth Symphony acquires the Spaethean lyric “Hel-lo! Hel-lo! What ho! What ho!” And then there was B. H. Haggin, a scourge of everyone else’s standards and tastes. Haggin’s “A Book of the Symphony” (1937) was accompanied by a ruler allowing the reader to find a given section of, say, the “Eroica” on a 78-r.p.m. record, the most common format of the time. A ruler to find musical passages!

Once Bernstein landed on broadcast television, in the mid-fifties, such guides looked pitiful. There he was on CBS, handsome and charming as he stood with other musicians on a floor printed with the staves of Beethoven’s Fifth, moving players around to achieve the proper Beethoven sound. A few years later, in 1958, he began broadcasting the “Young People’s Concerts” and continued for fourteen years, vamping and challenging the children (and, more likely, speaking to their parents) with shows on folk music and jazz along with such subjects as “humor in music” and individual programs devoted not just to Bach and Beethoven but to such hard-to-like composers as Sibelius. No one has ever been as good as Bernstein at talking publicly about music, but, in the early, glory days of FM radio, there were enthusiasts who broke the rules. On the beloved, long-gone New York station WNCN, there were d.j.s such as Bill Watson and Fleetwood, who, in the middle of the night, would play the complete “Well-Tempered Clavier” or a whole opera not once but twice.

Hurwitz is a descendant of Bernstein and the mad d.j.s, the heir to the most expressive of musical explainers and celebrants. In his hands, music appreciation has been liberated from boredom. He also exhibits a refreshing receptivity to changes in classical repertory, including the recent growth in programming that features work by historically underrepresented groups. For centuries, it was white men who composed and had their works performed because, Hurwitz said, “they were who they were and had the right connections. Ninety-nine per cent of the stuff they wrote was crap, and no one knows about it or cares about it now. So I have no problem giving some other group a chance. I don’t care who they are. Ninety-nine per cent of what they produce will still be crap, and the best will be just as good as the best historically.” His tendency to prefer recordings over live performance seems to reflect a similarly democratic impulse. “I think one element of classical snobbery is the insistence that live concerts (more expensive and more exclusive) are better or more valid than mass-produced consumer products such as recordings.” How can you tell how good something is until you’ve heard it a couple of times?

Even in the classical-music world, he insists, there are frauds and fools, and, most dangerous of all, arrogant pedants killing the pleasures of music with academic-extremist theories. The period-instrument movement, with its claims of historical “authenticity,” obsesses Hurwitz (and I agree with much of what he says). He’s not entirely against it, but at times he describes it as a commercially driven high-brow con: By the end of the sixties, he said, “people were bored, they wanted a new sound.” A cadre of gifted players (in London, Vienna, and other European cities), egged on by the record companies, saw a way of generating hundreds of albums.

Back in the seventies, as Hurwitz admits, Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s performance of the Vivaldi chestnut “The Four Seasons” with the Consentus Musicus Wien (extreme tempos, furious attacks) arrived like cold water dashed into your face. The period performers of the eighties brought clarity and hard-edged excitement to familiar scores—say, Handel, Gluck, and Mozart operas. But for all its discoveries and provocations, the period-performance movement is also given to intimidating orthodoxies and soul-defeating austerity. “What we have here,” Hurwitz said, “is great technical proficiency but an absence of character.” In his mind, musical and emotional expressiveness—not claims of historical correctness—should be the goals of performance.

Perhaps the matter comes down to taste, not history. Harnoncourt repeatedly said that he simply liked the sound of period instruments. Fair enough; that leaves resisters like Hurwitz and me free to say we don’t much like the sound of valveless horns, strings made from catgut, timpani that sound more like musket fire than thunder. Very few period scholars and performers, however, make claims as modest as Harnoncourt’s. They reconstruct what they say Bach, Mozart, or Beethoven heard, or wanted to hear. Yet isn’t it possible, even likely, that composers would have preferred modern performances, with their larger, better-tuned, better-disciplined, richer-sounding ensembles? And whose authenticity are we talking about? As the late music historian Richard Taruskin asserted, the celebrated period performers are indeed authentic—but what they are authentically reproducing is an explicitly modernist ethos (literalist, impersonal, wary of the profound or sublime), which they impose on the past.

The debate over historical performance was probably at its fiercest when Taruskin was inveighing against it in reviews back in the eighties. In the past couple of decades, the hostilities have entered a period of negotiated peace, and the battle lines are blurrier. It’s commonplace for an instrumentalist at a conservatory to take some course in historical performance, and plenty of performers play both historical instruments and modern ones. András Schiff, a historical-performance skeptic when he was recording Bach’s keyboard works on a modern piano, in the eighties, now sometimes plays Beethoven and Schubert on its forerunner, the fortepiano. Melvyn Tan, who came to prominence as a fortepiano specialist, has moved in the other direction, recording Debussy and even Beethoven on a regular grand piano. No classical performer is more mainstream than Yo-Yo Ma, but his successive recordings of the Bach cello suites have been strongly influenced by period-instrument practice in such matters as phrasing and the use of gut strings.

The great orchestras in Europe and the United States continue to use modern instruments, but they often employ some degree of “period practice”—reducing the number of strings, for instance, such that a Beethoven symphony comes off as slender and lithe rather than heroically massive, as in Karajan’s old Berlin Philharmonic recordings. Meanwhile, early-music ensembles, which once more or less confined their activities to the Baroque era and earlier, have inched forward chronologically, bringing historically informed methods to the music of the whole nineteenth century. I’m with Hurwitz on finding most of the results thin and unconvincing. In 2012, I heard John Eliot Gardiner, his Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, and his Monteverdi Choir perform Beethoven’s “Missa Solemnis” in Carnegie Hall. O.K., I got it: small orchestra, small chorus, clear contrapuntal lines; everything precise, rapid, and forceful. But the event lacked what a great performance of the “Missa Solemnis” requires—a sense of awe, the astonishment at the large mass of players and singers hurtling through Beethoven’s incomparable expressions of joy and grief. The performance lacked weight. And I had a similar experience with another period-instrument conductor, Roger Norrington, celebrated in Britain but one of Hurwitz’s biggest bêtes noires. “Roger Norrington—The Complete Worthless Dreck Edition” was Hurwitz’s gentle title for a video going through Norrington’s work, disk by disk.

On happier days, Hurwitz likes to spread the love around. Leoš Janáček! The Végh Quartet! Movie music! (He does, after all, run a record magazine that sells ads.) He can be especially welcoming to small labels, obscure orchestras, and forgotten conductors—for instance, the Hungarian Ferenc Fricsay, who made great records in the fifties and died young. To really know a great score, to bring it to life with a passionate intensity bordering on madness—how can art like this just fade away? Hurwitz celebrates these tremendous efforts and thereby serves as encouragement to today’s musicians. Toting up winners and losers in his freewheeling way, he can make you wince, but he is never unctuous, pompous, or timid—the frequent music-commentary vices. Nor is he feebly jocose like some of WQXR’s perennials, who seem to fear both music’s power and the simultaneous possibility that some listener somewhere might not like classical music at all.

“The music attracts the reticent fraction of the population,” my colleague Alex Ross has written. “It is an art of grand gestures and vast dimensions that plays to mobs of the quiet and shy.” They are quiet, in many cases, because they sense that no amount of persuasion will get anyone not predisposed to become obsessed with Josquin, Mahler, or even Beethoven. Abashed, they—we—withdraw into the company of the like-minded, or listen alone. Admittedly, this retreat is one of the few lonely experiences that can be satisfying.

Hurwitz does not think it strange to hold up CDs in a CD-walled den, despite the fact that we live in a time when physical media are increasingly supplanted by streaming alternatives. “I really don’t know what will happen with sound media,” he admitted. “I would have thought that vinyl was doomed, and yet here it is, back again at crazy prices. So all I can do is talk about the best—and worst—performances with a certain confidence that they will remain available, somehow, somewhere.”

“But you must feel a little forlorn at times, as if everything great had been done,” I suggested.

“It may surprise you, but I’m actually quite optimistic. Greatness is its own justification. When it comes to the standard repertoire, it thrills me to hear a splendid new version of something. If you believe that classical music is ‘classical’ by virtue of its undying relevance and repeatability, then I don’t think any other perspective is possible. I always hope that new releases will be stellar. Of course they aren’t, as often as not, and that just assures my own ongoing relevance!” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com