Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

On January 26, 2023, Israeli soldiers, hidden in the cargo hold of a dairy truck, rode into the Jenin refugee camp in the West Bank, where the Magnum photographer Sakir Khader was preparing to leave for his grandmother’s home in Nablus.

“Dying to Exist,” a recent collection of Khader’s photographs, opens with an account of what followed. WhatsApp messages between Khader and a friend allow us to reconstruct a time-stamped narrative of those hours as he experienced them:

6:23 A.M.: An alarm sounds in the camp, clashes between Israeli soldiers and locals begin.

7:40 A.M.: Bullets fly by.

8:13 A.M.: A boy is shot dead in front of Khader. His body lies on the street, and snipers shoot at anyone trying to remove it.

9:47 A.M.: Drones fly above.

10:58 A.M.: Combat helicopters soar overhead, Israeli forces fire rockets at a house.

11:14 A.M.: Reports say ten are dead.

While he sent messages to his friend, Khader was out taking photographs. The images that appear in Khader’s book draw from his archive and new images captured in 2019, 2023, and 2024, and form part of an ongoing series of photographs taken in Palestine. Images of massacres in Gaza have permeated public consciousness throughout the last two years; Khader shows a life in proximity to more insidious forms of violence in the West Bank that have recently become more frequent, more intense. “I’m visualizing an occupation,” he told me.

Mourners gather around the body of a man in Jenin; his headband is one of those worn by members of the Jenin brigades, a local armed group. September, 2023.

A man rides a horse. Jenin, Palestine, 2024.

Two children stand in the village of Rujib. Nablus, Palestine, 2024.

Khader’s photographs, like this image of a young girl in Jenin refugee camp, in 2024, often commemorate the aftermath of violence.

Khader was born in 1990 in the town of Vlaardingen, outside Rotterdam, to Palestinian parents. His paternal grandfather moved to the Netherlands from Nablus in 1965, following a job offer in a butter factory. As a child, Khader often returned to Palestine for family visits. He recalls sharing watermelons with his cousin Kosay under the pomegranate and fig trees of his grandparents’ neighborhood. Unaware of the occupation as children, the pair played adventure games, inventing characters in Nablus mountains. In 2002, an Israeli sniper shot and killed Kosay. “Since that day, I’ve carried his memory like a vow,” Khader writes in his book.

Mona and her daughter Alaa embrace at the very spot where Mona’s husband, Jawad Bawaqneh—Alaa’s father—was shot dead by Israeli soldiers.

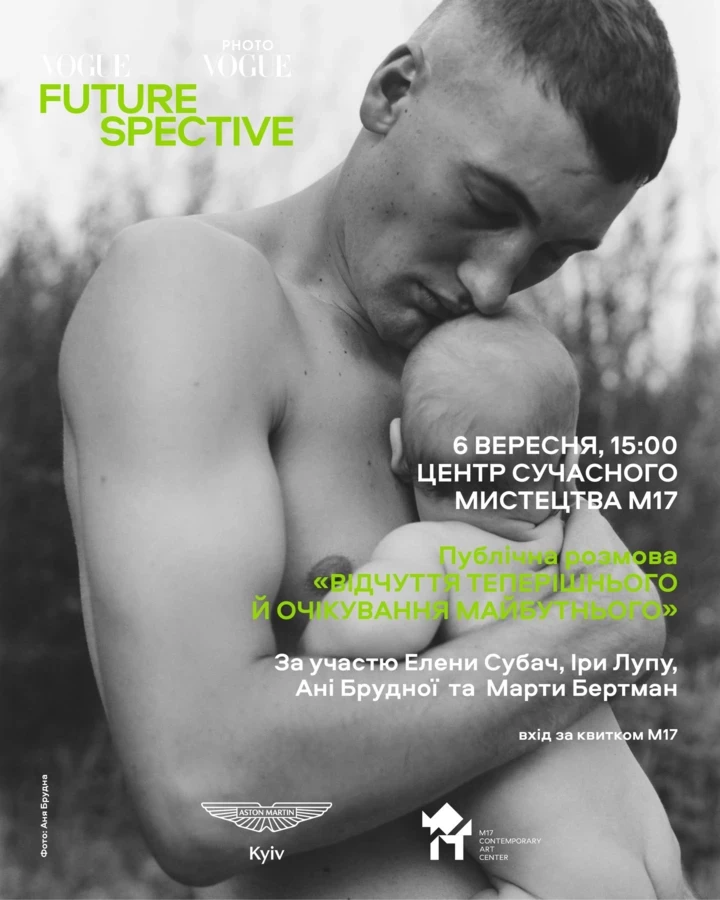

A man displays an injury, which he sustained during a major Israeli assault on the Jenin refugee camp in July of 2023.

Khader, who is self-taught, began filming the Jenin camp in 2017, during trips made to the city to document friends involved in the local theatre scene. In the spring of 2019, he began taking photographs and videos of the refugee camp, favoring an inexpensive Pentax camera. Until recently, the Jenin camp occupied half a square kilometre, with a population of some twenty-five thousand. Khader called it a “country within a country,” an ephemeral island of residents waiting to return to the homes they were expelled from in 1948. One of Khader’s early subjects was a fourteen-year-old boy named Amjad al-Fayed; when Khader met him, in 2019, Fayed could often be found riding his bike through the streets of the camp, or playing a game of soccer. Khader promised that he would return one day to make him the subject of a film. Three years later, Fayed was shot in the neck and chest, at close range, after trailing an Israeli patrol unit while carrying a pipe bomb.

The grave site of Amjad al-Fayed, Jenin refugee camp, Palestine, 2023. Fayed, one of Khader’s early subjects, was shot in the neck and chest in 2022, after trailing an Israeli patrol unit while holding a pipe bomb.

Oday Abu Na’sa, from Jenin, reveals the burns he suffered when a bomb exploded nearby.

Young men mourn in a hospital’s mortuary. January, 2024.

The Jenin refugee camp is a half square kilometre. Khader calls it a “country within a country.” As of January, 2025, nearly all of the camp’s residents have been displaced.

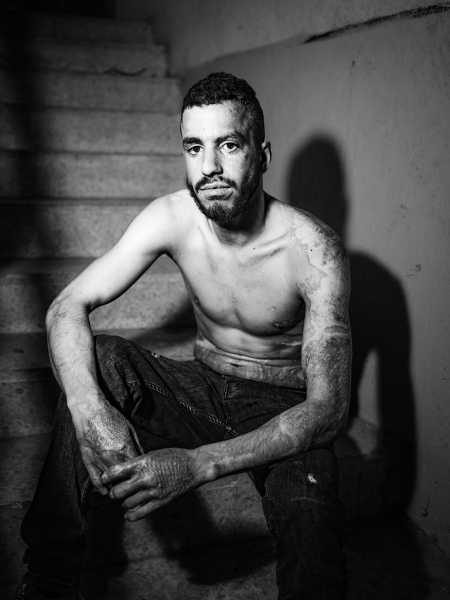

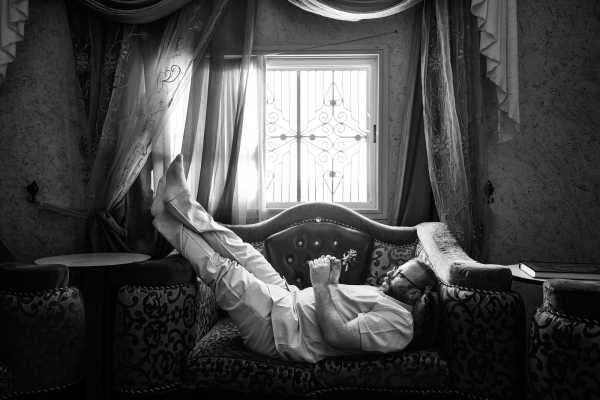

His work from Jenin often commemorates the aftermath of violence: an image of a young man standing before three bodies stacked in a hospital mortuary; a pillow on a stretcher spattered with blood. Some subjects reveal their wounds to the camera, bare skin covered in a tapestry of scars and burn marks. Elsewhere, a wall painted with a mural of the Al-Aqsa Mosque is pocked with bullet holes. But Khader also seeks to capture life lived against the backdrop of Israeli occupation. In one image, a group of young girls throw peace signs in front of a building whose façade has been entirely effaced. In another photograph, a man prostrates on the ground during prayer, the edge of his kaffiyeh grazing the soil beneath him in a gesture of devotion.

A man prostrates on the ground during prayer, the edge of his kaffiyeh grazing the soil beneath him. Nablus, Palestine, 2021.

A man in the village of Ajjah. Jenin, Palestine, 2024.

Khader returned to Jenin briefly in December, smuggled in by friends while the camp was besieged by the Palestinian Authority’s security forces in coördination with the Israeli military, as part of a crackdown on armed fighters. Some of the men he photographed were dead not long after. In January, mere days after a ceasefire in Gaza was declared, Israeli forces launched a particularly aggressive raid, resulting in the displacement of two thousand families. Khader visited again in February and discovered little trace of the Jenin that he once knew. “When I capture nowadays, it’s not guaranteed that I will find these places and these people when I come back,” he told me.

A blood-spattered pillow in Ibn Sina hospital. Jenin, January, 2024.

Palestinians’ resistance to their displacement is visible not only in images of young men brandishing weapons, Khader said, but in simple acts: an elderly woman tending to her land, remaining to care for her olive trees despite the ruins that now surround her. It is not often that Khader photographs unpeopled landscapes, but one of his images from Jenin shows the rocks and rubble left behind after a recent bulldozing. In the corner of the image sit three chairs—one can imagine three mothers returning to them, gathering over bitter coffee, exchanging stories of those they have loved and mourned. Even in absence, the audacity of the living remains.

A girl in the village of Rujib. Nablus, Palestine, 2024.

Sourse: newyorker.com