Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

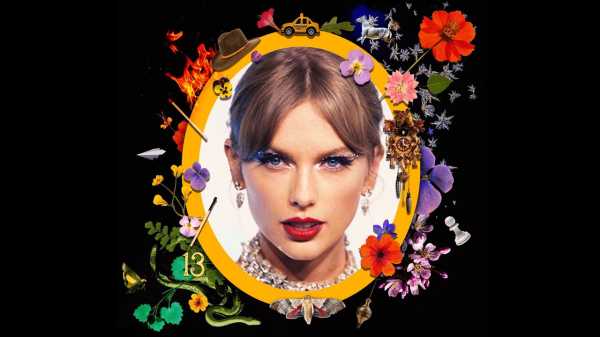

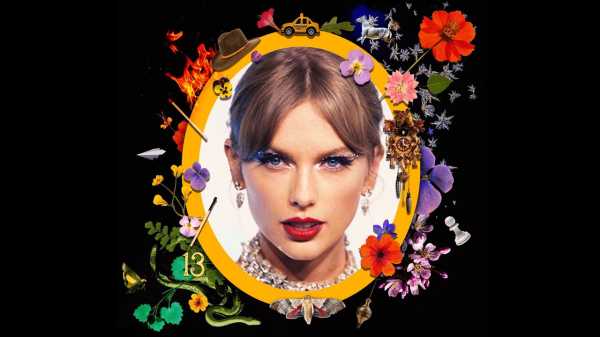

In 2014, Taylor Swift released an album called “1989,” marking her transition from country to pop. She went on “Jimmy Kimmel Live!,” where the talk-show host read aloud from some early reviews. Time magazine: “ [‘1989’] marks her most impressive sleight of hand yet—shifting the focus away from her past and onto her music, which is as smart and confident as it’s ever been.” Rolling Stone: “ ‘1989’ sounds exactly like Taylor Swift, even when it sounds like nothing she’s ever tried before.” The Times: “By making pop with almost no contemporary references, Ms. Swift is aiming somewhere even higher, a mode of timelessness that few true pop stars . . . even bother aspiring to.” The artist beamed: perhaps she knew it at the time, but this is the moment when Taylor Swift became Taylor Swift.

“1989” sold 1.287 million copies in the U.S. in its first week, breaking industry records. The singles, such as “Shake It Off” and “Blank Space,” remain some of Swift’s best-known songs, inescapable at a wedding or a karaoke bar. However, the success of “1989” was dwarfed, nine years later, by that of “1989 (Taylor’s Version).” The latter sold more than 1.6 million units in the U.S. in its first week and was the top-selling album in America in 2023. Apple Music recently listed it as the eighteenth-best album of all time, putting it slightly ahead of the Beatles’ “Revolver.” Was the new “1989” so much better than the first one? Not really—it was rerecorded to sound almost exactly the same, with songs like “Blank Space” essentially beat-for-beat facsimiles of the originals. And yet, whereas the first “1989” won three Grammys, “1989 (Taylor’s Version)” was eligible for another slew of awards, making one wonder how Swift was not running afoul of some kind of double-jeopardy rule.

Before Swift announced, in 2019, that she would be rerecording all of her music, she was facing what she called a “career death.” Three years prior, as part of an ongoing feud with Kanye West, she had objected to a lyric that he had written about her, in which he claimed to have “made that bitch famous.” In response, Kim Kardashian, then West’s wife, released an edited recording of a phone call in which Swift seemed to agree to the content of the song in advance. “She totally approved that,” Kardashian explained to GQ. “She wanted to all of a sudden act like she didn’t.” Kardashian posted a tweet about snakes that was apparently aimed at Swift, and snake emojis proliferated online, as did the hashtag #TaylorSwiftIsOverParty. For a time, Swift withdrew from public life. “Nobody physically saw me for a year,” she said. “That’s what I thought they wanted.”

In 2017, Swift released the album “Reputation,” which was meant to be her grand comeback, but it was snubbed at the Grammys. When she received this news, a moment caught on film in the documentary “Miss Americana,” she was near tears. “This is good,” she told a member of her team. “This is fine.” She added, “I just need to make a better record.” That next record, “Lover,” would contain some of Swift’s most beloved songs, such as “Cruel Summer.” But the first single, “ME!,” an earnest self-empowerment anthem, was such a disappointment that fans put forth a theory that it was not the album’s single at all but rather a one-off that she had written for the soundtrack for the upcoming sequel to the animated feature “The Secret Life of Pets.” (Some of the movie’s advertising imagery and the “ME!” music video had similar color palettes.) Swift later edited out one of the cringiest parts of the song, an interlude in which she shouts, “Spelling is fun!” The next single, “You Need to Calm Down,” a sunny song about L.G.B.T.Q. allyship, was released during Pride Month. Swift was simultaneously accused of making light of homophobia (“Shade never made anybody less gay”) and of queer-baiting fans by wearing the colors of the bisexual flag in the music video.

Later that month, Swift posted on Tumblr—not about “Lover” but about every album that preceded it. She explained that, when she was fifteen years old, she had signed a deal with Big Machine Records, giving the label ownership of the masters of her first six studio albums. For years, she had been trying to regain control of her masters, but Scott Borchetta, the C.E.O. of Big Machine Label Group, wouldn’t sell them to her. Instead, the label had offered a kind of trade: for every new album Swift made with them, she would receive an old one in return. Swift found the terms unacceptable. “I had to make the excruciating choice to leave behind my past,” she wrote. She had signed a deal with a new label, and would own the rights to all future albums, but she appeared to have given up on owning her previous work: “Music I wrote on my bedroom floor and videos I dreamed up and paid for from the money I earned playing in bars, then clubs, then arenas, then stadiums.”

The occasion for the post was that Swift had just learned that Borchetta had sold her masters to a record executive named Scooter Braun. Braun has been described by the Times as “the defining music executive of the social media era.” He’s been credited with discovering Justin Bieber, and has worked with Ariana Grande, Demi Lovato, and, crucially, Kanye West. Swift recounted the “incessant, manipulative bullying” she had received at Braun’s hands. “Like when Kim Kardashian orchestrated an illegally recorded snippet of a phone call to be leaked and then Scooter got his two clients together to bully me online about it,” she wrote. “Or when his client, Kanye West, organized a revenge porn music video which strips my body naked”—a reference to one of West’s music videos, which features a naked wax figure of Swift sleeping alongside Bill Cosby, Donald Trump, and others. “Now Scooter has stripped me of my life’s work.” (Braun later said he regretted Swift’s reaction to the deal and that he is against bullying. He also claimed that he had offered to sell the masters to her; Swift has alleged that he refused to quote a price unless she signed an N.D.A.) In her Tumblr post, Swift accused Borchetta of orchestrating the sale to Braun in order to punish her: “He knew what he was doing; they both did. Controlling a woman who didn’t want to be associated with them.”

Swift is certainly not the first artist who has fought for control of her work. Paul McCartney spent nearly fifty years trying to buy the Beatles’ catalogue. Kanye West and Prince have both been embroiled in battles over their masters, which they saw as emblematic of the music industry’s racism: West tweeted that “BLACK MASTERS MATTER,” and Prince compared record contracts to slavery. West, seemingly radicalized by the experience, even offered to do his former rival a solid: “I’M GOING TO PERSONALLY SEE TO IT THAT TAYLOR SWIFT GETS HER MASTERS BACK,” he tweeted, adding, “SCOOTER IS A CLOSE FAMILY FRIEND.” But West didn’t get Swift her masters back, and he didn’t get his back, either. Prince, meanwhile, famously changed his name in protest of his record label. He eventually got his masters back only by agreeing to a deal like the one that Borchetta offered Swift: after releasing two new albums through the label, he regained control of his older ones.

In retrospect, that Tumblr post might be one of the most important things that Swift has ever written. It has all the qualities of a good Taylor Swift song, conjuring an image of an innocent teen-ager who got in over her head, and the men intent on exploiting her. Whereas her predecessors struggled to get their fans to care about the inner workings of the music industry, Swift created a real-life story that, in a cleverly meta way, was all about why she deserves to own the stories she’s told. And these aren’t just any stories: as Swift later told Rolling Stone, Braun and Borchetta are “two very rich, very powerful men, using $300 million of other people’s money to purchase, like, the most feminine body of work.” When she announced that she would rerecord her first six albums—giving her the copyright to the new tracks—the plan was greeted by many as an act of feminist reclamation.

For the past few years, Swift has been rolling out these rerecorded albums, one at a time, in nonchronological order. Each one, appended with the phrase “Taylor’s Version,” has been ridiculously successful, embraced by both fans and critics. Perhaps most important, these releases created a virtuous way to listen to Swift’s music. Fans refused to stream the old tracks; radio stations committed to playing only the new ones. “Whenever Taylor re-records a new track, we immediately replace the old versions,” Tom Poleman, the chief programming officer of iHeartMedia, said in 2021. “Listeners have made it known that they cannot wait to hear Taylor’s Version of each track.” Last year, a video came up on my Instagram feed. “ ‘Taylor’s Version’ means no one steals her albums,” a little girl tells her sister, as the two of them sit in their playroom. “And the meanie bug who stealed her albums name is Scooter Brahms.”

“Not Brahms,” the other girl says. “Braun.”

The irony is that, by this point, Braun no longer owned Swift’s masters. In 2020, he sold them to Shamrock Capital, a private-equity firm spun off from the family investment office of a member of the Disney family. Still, Swifties continued to refer to the original albums as “Scooter’s Versions.” And the enemy was no longer just Braun but anyone who chose the old songs over the new. Several months ago, I saw a viral TikTok of a girl in a sequinned dress vibing out at an event to Swift’s “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together”—until she realizes that something is awry. The chorus hits; her eyes bulge. “It’s not Taylor’s Version!” she screams. The video has 3.4 million likes, and the comment section is split between sympathetic Swifties and confused casual listeners. “I will refuse to dance/sing or even bop my head if it’s not taylors version,” one user wrote. Another asks, “Is it not the same . . . ?” To the most devoted Swift fans, this was like asking if Columbus Day is the same as Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

In March, 2023, Swift took her feminist crusade on the road with the Eras Tour: the highest-grossing tour of all time, which made Swift the first musician to become a billionaire primarily on music earnings. The tour, inspired by Swift’s rerecording project, was a mix of live performance and live promotion; at certain shows, she teased the release of the next Taylor’s Version, sending fans into a frenzy over the possibility of hearing new old music. Late last year, the six-hundred-and-thirty-two-day tour finally came to an end. Curiously, two album rerecordings—the artist’s eponymous début and “Reputation”—had yet to be released.

It is possible that neither album will ever be released. The week before last, Swift announced that she had struck a deal with Shamrock Capital to buy back her masters. “All of the music I’ve ever made . . . now belongs . . . to me,” she wrote, in a letter on her website. While that first letter, about the Braun purchase, concluded with the valediction “Sad and grossed out,” this one ended with “Elated and amazed.” The rerecordings era was officially over. Swifties, meanwhile, have celebrated by reintroducing the Scooter’s Versions, which are now also Taylor’s Versions, back into their lives. And, more quietly, they’ve started to admit that maybe the rerecordings were never that great to begin with.

It was all so promising at the start. In April, 2021, Swift released “Fearless (Taylor’s Version).” The original “Fearless,” from 2008, launched her to international fame and gave us both “Love Story” and “You Belong with Me,” which are still among her most popular songs. It won Swift her first Grammy, and a 2009 MTV Video Music Award. (This marked the start of her feud with West, who interrupted her acceptance speech to declare that Beyoncé was the rightful winner.) For fans of the original, “Fearless (T.V.)” was underwhelming, but in a good way. The rerecorded tracks are loyal to the originals; some sound almost as if they’ve simply been remastered. The mix is clearer, and the instruments are sharper. As Michael A. Lee, a music professor at Azusa Pacific University, told Entertainment Weekly, the piano in “Forever & Always (Piano Version)” has gone from sounding like an “upright, almost honky-tonk,” to sounding like a grand. In “Change,” the guitar solo is less distorted. Over all, Lee said, the album is an almost identical remake of the original—a technically difficult task to pull off.

The main difference is the quality of Swift’s vocals, which had improved dramatically in the thirteen years between the initial release and the rerecording. On the original, Swift sounds shaky and nervous—understandable, as she was only eighteen. But on the rerecording her voice is deeper and fuller. I was never a huge fan of the original “You Belong with Me,” because it felt as if Swift was mostly speak-singing. The pre-chorus featured a silly line—“She’s cheer captain and I’m on the bleachers”—made sillier by its delivery. But on the Taylor’s Version the line is more melodic, and she enunciates more clearly. (Similarly, on the rerecorded “1989” album, it is finally possible to tell that Swift is singing about a “long list of ex-lovers” rather than “all the lonely Starbucks lovers.”)

Some of the lyrics on “Fearless” are almost stunningly earnest. Others seem mature beyond their years, a feeling that is acute when listening to the Taylor’s Version. In general, there is something touching about hearing an older Swift return to some of her earliest songs. After she rerecorded “Never Grow Up,” a song on “Speak Now” that she wrote in her late teens, fans uploaded videos splicing the two versions of the track together. One listener wrote, “This totally has the feel of a younger and older sister sitting next to each other on wooden bar stools up on a small stage with their guitars and just strumming and vibing into their microphones.”

Revisiting “Fearless,” Swift has written, was “more fulfilling and emotional than i could have imagined.” And it was an important proof of concept. The album went to No. 1—the first time that a rerecorded album has topped the charts—and had the biggest sales week for any country album since 2015. Many newer fans were also exposed to her early tracks for the first time. I discovered what is now one of my favorites, a deep cut called “The Other Side of the Door.” When Swift played the song as a surprise on the Eras Tour, she grinned when fans seemed to know every word.

After “Fearless (T.V.),” there was a lot of excitement about the rerecordings to come. But the next two, “Red (T.V.)” and “Speak Now (T.V.),” were significantly worse in quality. Part of the issue lay with the spirit of the original albums: though both were made after “Fearless,” they’re more melodramatic, in the way that a moody teen-ager can appear more immature than her precocious younger sibling. Some of the songs seem designed to be screamed by heartbroken girls in their bedrooms, and it was difficult for Swift, now in her thirties, to re-create the necessary angst. “Last Kiss,” on “Speak Now,” is thought to be about the demise of Swift’s relationship with Joe Jonas, who reportedly dumped Swift over the phone. The track’s intro is twenty-seven seconds long—the supposed length of that breakup call—and, by the time that Swift starts singing in the original version of the track, one gets the sense that she spent the song’s intro reliving that phone call. In the final verse, she gets audibly choked up. Before the release of “Speak Now (T.V.),” I was worried that, if she faked this, it would sound overwrought. Instead, she didn’t even try, and that was somehow worse. On the Eras Tour, we’ve seen Swift recapture old emotions: a video of her voice cracking and her eyes welling up during a performance of “I Don’t Wanna Live Forever” went viral. But, without the caught breath in “Last Kiss,” the song feels oddly distant.

On the Taylor’s Versions, it can be hard to tell which changes were unavoidable and which ones were premeditated. Many fans have speculated that it would have been impossible for Swift to make a faithful rerecording of “Mean,” a country song directed at her critics, given that, at the time of the initial recording, she had a southern accent. (Other fans, like myself, argue that the southern accent was always embellished: Swift moved to Nashville from Pennsylvania when she was fourteen, and started putting out country music with a full-on twang at sixteen.) And yet, on the new recording, there’s a mismatch between the lyrics, which are hard to even read without imagining the accent—“Someday, I’ll be livin’ in a big ol’ city / And all you’re ever gonna be is mean”—and Swift’s straightforward delivery.

A few changes were clearly intentional. In the original version of “Better than Revenge,” Swift sings, in reference to her ex-lover’s new girlfriend, an actress, that “she’s better known for the things that she does on the mattress.” (Some Swifties on Instagram still take pleasure in harassing Camilla Belle—the alleged muse of the song, who dated Jonas after Swift.) In the rerecording, Swift changed the lyric to “He was a moth to the flame, she was holding the matches.” Undoubtedly, Swift, who was in the midst of a project of female empowerment, would have taken heat for a slut-shaming lyric. Still, the change felt strange. Swift has said that she was proud of “Speak Now” because it was the first album that she wrote entirely by herself. Listening to it was like reading her diary—the kind of authenticity that has made Swift’s fans feel so close to her. If she were to change every lyric on the album that felt misguided or hyperbolic, she wouldn’t have any left.

The most drastic change that Swift made was to “Girl at Home,” a soft country song on “Red” that she turned into an electro-pop track. As one listener wrote on Reddit, “twerking to girl at home wasn’t on my 2021 bingo card.” In recent years, other artists have released similarly imaginative rerecordings. In 2023, Demi Lovato released “Revamped,” an album with “rock versions” of some of her pop hits. Kanye West rerecorded his track “Say You Will” with the classical musician Caroline Shaw. For Swift, changing the production of “Girl at Home” was only a mild creative risk. But it did make me wonder what it would have been like if she had reimagined more of her work. Perhaps she would have released a rock version of “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together,” similar to the one that she performed live on the “1989” tour. Or a rerecording of “Wildest Dreams,” with the dramatic drums that kick in during the final chorus of the music video. If I listened to the music-video version, as I often did, was I supporting Scooter Braun?

By trying to make carbon copies of her original songs, Swift created problems. Production changes stand out—the volume of a synth or the overuse of reverb can sound like a push notification interrupting your listening experience. Occasionally, there are new mistakes. In the middle of “All Too Well (T.V.),” on the rerecording of “Red,” two different cuts have seemingly been spliced together, causing Swift’s voice to jump.

Sometimes there’s not an error, per se, but just a feeling that something is wrong. It’s a feeling that’s reserved for Swift’s most diehard listeners, the fans who have long used her music as a kind of soundtrack to their lives. People who have only heard her songs in the grocery store, or at a bar, will have no idea what I’m talking about, which is perhaps why the rerecordings project, on the whole, has been uncontroversial. The feeling arises in a different song for every Swiftie: I’m generally O.K. with “Shake It Off (Taylor’s Version),” from the rerecorded “1989” album, for instance, but one of my colleagues said that her two-and-a-half-year-old daughter completely rejected the rerecorded track and asked for “other ‘Shake It Off’ ” instead. I get it.

My favorite Swift song of all time is “Style,” which is also on the “1989” album. The track is about the experience of an on-again, off-again relationship. Swift, too, has said that it’s her “secret favorite.” “I love when the sound of a song matches up with the feeling that inspired it,” she once explained. From the opening notes of the rerecording, though, the sound is different, or at least it is to me. The thin guitar riff at the start of the original song sounds fuller and more resonant, absent of grit—even though it was that rough, almost abrasive sound that helped Swift capture the experience of messy love. The claps are crisper, and the snare drums smack harder, but the sound is sterile. I also find myself overwhelmed by certain digital sounds—that were either brought to the foreground of the production, or that weren’t there before—such as an annoying tinkling noise in the background of the chorus that feels straight out of Swift’s more recent album “Midnights.” The over-all effect is like watching a movie that’s supposed to be set in the nineties and spotting a Tesla in the background.

Part of the issue is that “1989” just isn’t that old. Swift’s vocals improved a lot in between the release of “Fearless” and “Fearless (T.V.),” but “1989 (T.V.)” sounds a little like bootleg karaoke. (One fan, who agrees with me on the changes to “Style,” wrote that the Taylor’s Version “sounds like Kidz Bop”—perhaps the most cathartic Reddit comment I’ve ever come across.) The more recent the song, the more likely that the rerecording will sit in an uncanny valley, not quite different, but not quite the same.

There is one big problem with “1989 (T.V.)”—a problem that can actually be proved. I initially found a few tracks unlistenable because of a distinct, high-pitched noise in the background. I asked some friends to listen, and they told me they had no idea what I was talking about; it seemed that listening to Taylor Swift had finally melted my brain. But later a few online Swifties using spectrograms identified a fifteen-kilohertz buzz on some of the tracks. A fan noted that Swift had likely recorded parts of the album at her house, where she has a studio, and theorized that, somewhere close to the microphone, there was a television that was creating a current in the wire. The result was a sound that only some listeners could hear, depending on their age and how damaged their hearing was. (I guess wearing earplugs at the Eras Tour, like a chump, served me well.) “Because most people over 25 can’t hear it, no one noticed,” one Swiftie wrote on Reddit. A group of fans lobbied for the sound to be removed. As of now, the issue has mostly been fixed, though not entirely. The cruel irony is that, had there been an issue like this with the original “1989,” which Swift recorded in her early twenties, she would likely have heard it herself.

One triumph of “1989 (T.V.),” and of the rerecordings more generally, are the bonus tracks “From the Vault,” which comprise previously unreleased songs. For Swift, they’ve been an exercise in lore-building. The implication is that her label didn’t think the songs were good enough to include the first time around; by releasing them now—to great success—she is able to affirm that she knows better than the bigwigs. It’s hard to listen to “Nothing New,” a vault track from “Red (T.V.)” featuring Phoebe Bridgers, and disagree. For that same album, Swift also released a ten-minute version of “All Too Well.” The story is that Swift was so caught up in writing the original that she kept adding verses, but then had to cut it down. The extended cut is now the longest song to ever go No. 1 on the Billboard charts.

I often wondered if fan interest in the vault tracks had led Swift to prioritize these songs over the rerecorded tracks. (Did an issue with the short version of “All Too Well (T. V.)” even matter if everyone was listening to the new extended one?) I’ve also found it hard to believe that some of the vault tracks were truly written more than a decade ago. Occasionally, there is an anachronism—singing “Fuck the patriarchy,” say, in a song written in 2011, or a seeming reference to a feud that is known to have occurred later. And it was probably right to cut some of the tracks in the first place. (I’m looking at you, “Suburban Legends.”) What’s perhaps more alarming is that this quantity-over-quality ethos has bled into Swift’s new studio albums. “The Tortured Poets Department,” her most recent, included thirty-one tracks, many of which could have been left on the cutting-room floor.

Most artists have had little success rerecording their music and getting the world to listen. In 2018, the pop star JoJo rerecorded her first two albums, while in the middle of a dispute with her former record label. But the new tracks don’t have nearly as many listens on Spotify as the originals. In general, rerecording is expensive and time-consuming, and few artists have the leverage to get audiences to shun the old versions of their songs. Still, the industry isn’t taking any chances; in 2021 Swift’s current label, Universal Music Group, reportedly began making artists sign contracts effectively doubling the time span in which they’re prohibited from rerecording their music.

So where did the Taylor’s Versions, despite their indisputable commercial success, go wrong? The main takeaway might be that it is extremely difficult to re-create a Max Martin song. Martin is a legendary Swedish hitmaker who wrote and co-produced Britney Spears’s “. . . Baby One More Time” and co-wrote and co-produced the Backstreet Boys’ “I Want It That Way.” He is also behind some of Swift’s most famous songs, including “I Knew You Were Trouble,” “We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together,” and “Shake It Off.” Yet Martin did not return for the Taylor’s Versions. “When you get it perfect—I mean perfect—the first time, why would you bother recreating it?” one Swiftie wrote on Reddit.

If it’s hard to re-create a Max Martin song, then it’s almost impossible to re-create one quickly. Swift put out the Taylor’s Versions at a steady pace of two per year; in the same period, she also released two new studio albums and travelled to five continents to perform a hundred and forty-nine sold-out shows. Perhaps the best explanation for some of the problems with the rerecordings is that Swift was rushing through them. In June, 2021, Swift announced that the next rerecording would be “Red (T.V.).” But, that September, she surprised everyone by dropping “Wildest Dreams (T.V.),” a track off “1989.” Why the switch? As it turns out, the original “Wildest Dreams” had started going viral on TikTok, raising its streaming numbers. Swift seemed to be following the money.

All of this—combined with the staggered rollout schedule, synchronized merch drops, and albums’ vinyl variations—contributed to the feeling that the rerecordings had gone from a feminist crusade to a capitalist cash grab. Swift was recycling I.P. to make old songs go No. 1 again, just as Disney releases soulless live-action remakes of animated classics. As it turns out, Swift’s project may have been a different kind of cash grab than anticipated. In the letter announcing that she had bought back her masters, Swift told fans that it was the success of the rerecordings and of the Eras Tour that made the purchase possible. Swift reportedly paid roughly three hundred and sixty million dollars for her music, which is less, in adjusted dollars, than what Braun is thought to have sold them for in 2020. With the help of fans, she devalued her old music—shorted her own stock—then bought it at a discount.

Is this feminism? It’s certainly clever. And the fans don’t feel swindled. They’re honored to have been part of a project that was much larger and more ambitious than they even realized. “This is the charity i was donating to when i spent every dollar i had on the eras tour btw,” one Swiftie posted on X. Another fan, on TikTok, said, “I did the math and each second of song was worth roughly $13k. so my $250 concert ticket contributed to 19 milliseconds.”

Some fans are disappointed that we may never see the last two rerecordings, though Swift has hinted that she might be willing to release them, in some form, one day. In her letter, Swift was candid about her struggles to rerecord “Reputation,” from 2017. “The Reputation album was so specific to that time in my life, and I kept hitting a stopping point when I tried to remake it,” she wrote.

Now even some of the most fervent Taylor’s Version listeners are letting go of the lie. “This is like swiftie Independence Day,” one fan wrote on X, in a post that received sixty-seven thousand likes. “BRING BACK REAL MISOGYNY,” another fan wrote on the platform, posting the original version of “Better Than Revenge.” But, for me, the post that really hit hard was one from a Swiftie who had written, back in January, 2025, that “style tv is sounding better day by day.” The fan quote-tweeted her own post on May 30th of this year, and captioned it “you lying bitch.”

“Being able to re-listen to the og taylor swift albums is the modern equivalent of your husband returning from war,” one fan wrote. And then there are the purest fans of all: the ones who joined the fan base during the rerecordings era, and who have never even heard the O.G. albums. “Listening to the original 1989 for the first time ever,” one user wrote, on Reddit. She said that a lyric from “Welcome to New York,” in which Swift sings “It’s a new soundtrack, I could dance to this beat,” made her cry. “Of course, really it’s an old soundtrack,” the fan added, “but it’s new to me, and I can finally dance to this beat.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com