Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

A year ago, I wasn’t sanguine about the state of ultra-low-budget filmmaking; this year, the D.I.Y. domain accounts for many of the best new releases. What I’m still not sanguine about is the economic prospects for such movies, which, even in the best of times, were shaky box-office propositions. This may not matter for the films themselves, insofar as the best movies, the ones that open new prospects for the art, are made for the future (and the few who see that future in them) as much as for their own time; they reach large audiences only by happy coincidence. But it matters greatly for filmmakers, because early commercial failure may curtail promising careers.

On the other hand, sometimes the few who discern merit in a small, unprofitable movie include producers, financiers, and others with the power to make things happen. RaMell Ross’s exquisite 2018 documentary, “Hale County This Morning, This Evening,” took in only $112,282 at the box office, but it got him the chance to direct his first dramatic feature, “Nickel Boys,” with a budget of more than twenty million dollars. That’s good news for Ross, of course, but it’s also good news for the cinema at large—because the remarkable conceptual and aesthetic innovations of his new movie couldn’t have been realized on a shoestring budget. This year’s best releases are crucial reminders of the vitality and the invigorating energy of independent filmmaking—at all levels, ranging from the megamillions that Francis Ford Coppola personally pumped into “Megalopolis” to the hard-scrounged microbudgets of “Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point,” “My First Film,” and “The People’s Joker” (which was launched with a crowdfunding campaign).

A year, though real enough celestially speaking, is a cinematic artifice. It’s hard to glean trends from a year’s releases, because what’s released depends on the vagaries of production and distribution—the happenstance of which directors have movies in the works at a given moment, which movies premièring at festivals get acquired by a distributor for U.S. release. Some films that might have made it to my 2024 list (“On Becoming a Guinea Fowl,” “Eephus,” “Misericordia”) are now scheduled for 2025, and others (“Subtraction,” “Suburban Fury,” “Vas-Tu Renoncer?”) have no U.S. distribution. Still, the movies on the list do suggest a shared theme that has been latent in new releases for a while: the expansion of the art.

That may sound vague and grandiose, but a specific kind of expansion has recently been in evidence among many of the best new films. The point-of-view shots in “Nickel Boys” that vertiginously unite viewers and characters, the live performance of an actor who pops up in person and seemingly interacts with Adam Driver during screenings of “Megalopolis,” the pointillistic fragmentation of “Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point,” and the multiple levels of fiction and autofiction in “My First Film” all suggest an expanded cinema that doesn’t so much break film frames as it displaces them off the screen—that doesn’t make movies less cinematic but cinematizes life.

Such concepts and practices have been around for a long while, and so has the term “expanded cinema,” which gained prominence (with an altogether different meaning) as the title of a remarkable 1970 book by Gene Youngblood on the use of advanced technology in avant-garde films. Francis Ford Coppola’s 2017 book “Live Cinema and Its Techniques” is based on concepts that he had been mulling since the nineteen-fifties and developing since the nineteen-seventies. If these ideas are only now being openly advanced in a wide range of works by a multigenerational set of directors, I think it’s no accident: thanks to the prevalence of streaming and the watching of movies on cell phones or wherever, the very notion of the theatre and the fixed gaze at its screen has come to seem secondary and inessential to the cinematic experience.

That’s precisely why this new variety of cinema has come to the fore—not to concede movies to the pocket-size travelling show but to reclaim them from it. These new movies offer a new kind of spectacle, one that’s not just a matter of audiovisual bombast but that inheres in cinematic form, becomes part of a film’s narrative architecture, and creates a distinctive psychological relationship with viewers. This expanded cinema gives life to a movable spectacle, to one that can survive from format to format and won’t generate anything like the now clichéd disproportion of watching “Lawrence of Arabia” on a cell phone. With the new cinema, it isn’t the images that get small but the ideas that get big.

Despite the innovative extremes of the year’s best movies, the most exciting cinematic experience I had in 2024 involved a program, at BAM, in April, of four silent Japanese movies made between 1917 and 1933—one live-action film from each of the the two greatest Japanese filmmakers (a short by Yasujirō Ozu and a feature by Kenji Mizoguchi) and two animated shorts. The movies were presented in the manner that, in their time, was standard in Japan: with live accompaniment by performers, called benshi, who stood next to the screen and functioned as m.c.s, narrators, and actors. Each benshi—one per film—introduces the film and then, while the movie plays (with live musical accompaniment from a small band featuring both Japanese and European instruments), describes the action (with literary flair and dramatic verve) and also gives voice to the characters, providing and performing dialogue with keen interpretive variety.

With the rise of talking pictures in Japan, in the mid-thirties, the art of the benshi largely vanished, but in recent decades it has been cultivated anew and deployed at revival screenings. The result is entrancing, astonishing, even startling, both for its immediate dramatic thrills and for its wider implications. Though I’d felt that I’d seen acting of sublime refinement and inventive magnificence, I also had the sense that I’d experienced something that was neither quite like moviegoing nor like theatre. Rather, just as opera, which combines music and theatre but is an art in itself and different from both, so movies with benshi accompaniment are—despite their practical basis in the ordinary habit of moviegoing—transformed into an altogether separate art.

The lesson is jolting: from the start, the cinema was expanded. Whether with the rise of talking pictures, the radio-based and theatrically inspired innovations of Orson Welles, the development of immersive cinema-vérité documentaries along with their metafictional implications, or the notebook-like immediacy of movies made with lightweight digital video, the cinema has always been breaking out of its onscreen cloister and taking its place in the world. Now it’s doing so openly, boldly, self-consciously, and with a sharp sense of purpose. In 1970, Youngblood understood aesthetic advances in social and political terms: “We can now see through each other’s eyes, moving toward expanded vision and inevitably expanded consciousness.” The new cinema is an inherent part of a struggle for inner and outer liberation, for the reckoning with unacknowledged realities in clearer and more personal ways. Filmmakers whose movies have been part of that struggle this year could certainly not have known in advance how the election would turn out—but they filmed as if affirming that, no matter what, the struggle is ongoing and is inseparable from their artistic quest.

1. “Nickel Boys”

It’s hard to adapt a good novel, because the necessary directorial freedom runs up against the fear of betraying the admirable source, but RaMell Ross, in his first dramatic feature, creates a bolder, riskier, and more imaginative adaptation (of Colson Whitehead’s superb 2019 novel) than any other recent filmmaker. He turns a sharply observed, naturalistic third-person narrative—a story of two Black teen-agers trapped in a cruel and murderous, and segregated, juvenile-detention facility in Florida, in the nineteen-sixties—into the subjective visions of the two friends’ perspectives, shot from their points of view, with the requisite complex choreography of action and camera. The result is a form that elevates the very notion of point of view into a moral and political challenge of the highest order, in movies and in life at large.

2. “Christmas Eve in Miller’s Point”

In the writer-director Tyler Taormina’s hands, the clichéd premise of a memory-rich family drama set during the holidays yields a comprehensively original film. Its mosaic-like structure and epigrammatic dialogue are propulsive, its characterizations high-relief yet finely etched, its performances prickly yet tenderly observed, and its over-all style as colorfully enticing as it is subtly ambivalent.

3. “Megalopolis”

Photograph from Lionsgate Films / Everett Collection

The politics of Francis Ford Coppola’s futuristic science-fantasy, which layers ancient Rome and the New York of tomorrow, are as ingenuous as its whiz-bang cinematic inspiration, because its closest parallels are the adolescence of the cinema itself: silent movies. The grand-scale and high-energy images befit the cosmic imagination of silent-era spectacles; the performances delivered in forum-filling diction match the expressionistic fury of nineteen-twenties movies, too.

4. “My First Film”

Another adaptation at an audacious level of form: first, Zia Anger turned the story of the making of her unreleased first feature into a performance piece that she delivered in movie theatres; then she transformed that performance into a new feature. The result dramatizes the making and unmaking of the suppressed film and also weaves in her first-person, frame-breaking retrospective account of the doomed production. This is painfully personal filmmaking that’s principled and diagnostic regarding the practical and ethical conflicts of the art.

5. “Oh, Canada”

Reuniting with Richard Gere for the first time since “American Gigolo” (1980), Paul Schrader makes the years weigh heavily in a drama (adapted from a novel by Russell Banks) about the reckonings of a portrait of a terminally ill filmmaker (Gere) who first came to prominence as a draft evader, in Canada, during the Vietnam War. Despite his infirmities, the filmmaker agrees to be interviewed for a documentary but insists that his wife (Uma Thurman) be in the room so that he can confess to her the story of his youth, in the nineteen-sixties—an era that Schrader depicts, in flashbacks, with passionate energy and equally passionate regret, and a pugnacious sense of form to match.

6. “Blitz”

History writ large on an intimate scale: with fervent melodrama and elemental adventure, Steve McQueen delivers the big story of London uniting under aerial bombardment during the Second World War while also revealing, as with cinematic X-rays, the hidden fractures threatening British society—during the war and long after. Saoirse Ronan, who has long been deployed by lesser directors for her technique, here gets to unleash her temperament and expand her very presence, yielding her most exciting and engaging performance to date.

7. “Between the Temples”

Photograph by Sean Price Williams / Sony Pictures Classics / Everett Collection

Nathan Silver’s exuberantly abrasive quasi-romantic comedy, about a widowed cantor (Jason Schwartzman) who’s recruited by his long-ago music teacher (Carol Kane) to give her bat-mitzvah lessons, is also an acerbic view, in the Philip Roth vein, of Jewish norms and institutions—and a loving embrace of disorganized religion.

8. “The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed”

The writer and director Joanna Arnow crafts a wry and poignant aesthetic and a tense emotional climate for the story of a young Brooklyn woman in a numbing office job who struggles to fulfill her conflicting desires for both a submissive relationship and a romantic one. Arnow, starring as the protagonist, also develops a bold, melancholy choreography for one of the year’s most original performances, in synch with her precise camera style.

9. “Juror #2”

Using urgently direct methods with uninhibited freedom, Clint Eastwood fashions a courtroom thriller—about a juror with a personal connection to the case he’s deciding—into a scathing consideration of the ease with which demagogues and deceivers can manipulate the legal system into cruel injustice.

10. “It’s Not Me”

Leos Carax’s barely feature-length self-nonportrait is a free-flowing conjuring of personal connections and emotional attachments, a venting of passions by way of imagistic furies, and a toy chest of exuberant, intimate-scaled inventiveness.

11. “Hit Man”

Richard Linklater rings wry changes on the themes of identity and self-transformation in a comic film noir—based on a true story—of a nerdy psychology professor who’s recruited by police to impersonate hit men for sting operations. The resulting romantic and criminological twists are matched by the gleeful energy of the cast, headed by Glen Powell and Adria Arjona.

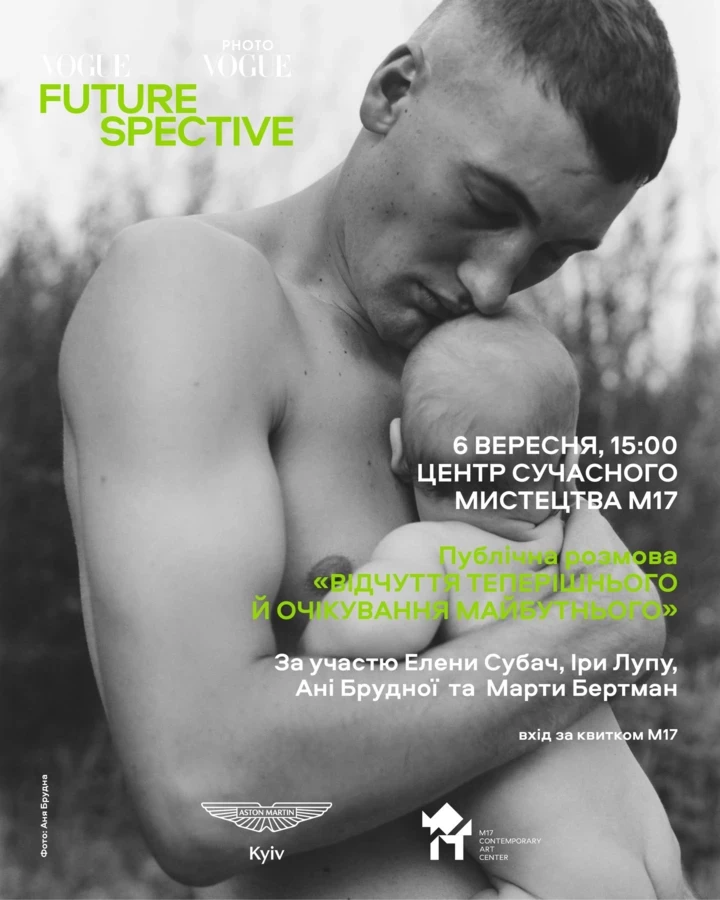

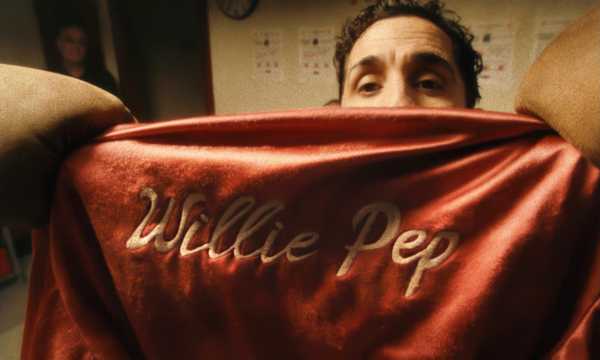

12. “The Featherweight”

Photograph from Sunrise Films / Everett Collection

A marvel of historical re-creation, Robert Kolodny’s fictitious documentary, about the real-life boxer Willie Pep’s attempt at a comeback in 1964, evokes with equal deftness the physical world of Pep’s place and time along with emotional and social worlds that were leaving him behind.

13. “Evil Does Not Exist”

The best documentary moment in the year’s movies (a scene that turns woodchopping into a mini-thriller) is found in this drama, by Ryusuke Hamaguchi, about a factotum in a Japanese mountain village who becomes embroiled in local resistance to the construction nearby of a glamping lodge.

14. “I Saw the TV Glow”

Jane Schoenbrun’s second dramatic feature develops a distinctive trans cinematic aesthetic in its tale of two adolescents whose obsession with a TV superhero enables them to dramatize the agonized self-denial they feel as a result of pressure to reject their identities.

15. “Last Summer”

Catherine Breillat’s tale of a dubious (and, in France, illegal) sexual relationship between a woman and her husband’s adolescent son is presented as an idyllic albeit imprudent adventure, and yet it turns into an emotionally brutal drama of power plays and the social and civic institutions that foster them. Great films outleap their creator’s intentions.

16. “The People’s Joker”

This D.I.Y. parody of the superheroic universe, directed by Vera Drew, also stars Drew, as a trans teen who escapes a repressive religious town, arrives in a futuristic urban dystopia, and tries to make a new life as an outlaw comedian. The simple but outrageous special effects and phantasmagorical leaps of imagination are as pointedly critical as they are giddily spectacular.

17. “Dahomey”

Photograph from MUBI / Everett Collection

Mati Diop’s documentary, about France’s repatriation, in 2021, of twenty-six art works plundered in 1892 from the Kingdom of Dahomey, in present-day Benin, looks intimately at the political and cultural legacy of colonialism and at the physical peculiarities of transporting art. In addition, Diop’s fictionalization of a long-ago Dahomeyan monarch, whose sculpted likeness is among those returned, highlights the way that art can embody the living memory of history.

18. “No Other Land”

An earnest but fraught friendship that develops between a Palestinian activist and an Israeli Jewish journalist, as they team up to report on—and to resist—Israeli demolitions in and around the activist’s village, gives rise to this documentary, which is at once trenchantly reportorial, revealingly historical, and painfully personal.

19. “The Seed of the Sacred Fig”

The courage of the Iranian director Mohammad Rasoulof and his cast and crew in secretly making the film is matched by the unyielding principle of the work itself. A middle-aged official in Tehran is promoted, becomes an investigative judge, and is appalled to learn that he’s required to rubber-stamp death sentences for young protesters. His wife embraces the family’s new privileges, but their two daughters, a teen-ager and a university student, support the protests. When the new judge’s newly issued gun goes missing, he suspects a member of his family, and the movie takes a climactic leap into intense melodrama that borders on grand tragedy. With a blazing yet meticulous combination of action, setting, and performance, the astonishing dénouement is reminiscent of masterworks by D. W. Griffith.

20. “Sasquatch Sunset”

The Zellner brothers, David and Nathan, deliver this story of four members of a forest-dwelling Sasquatch family in the Pacific Northwest utterly straight. The setup risks absurdity—the cast (which includes Nathan) essentially wears gorilla suits—but the premise is developed with meticulous and quasi-biological specificity, anthropological rigor, and imaginative speculation about the creatures’ emotions and senses of selfhood.

21. “Winner”

Susanna Fogel’s surprisingly breezy yet fervently committed drama, of the N.S.A. contractor Reality Winner’s release of secret documents revealing Russian interference in the 2016 Presidential election, has the line of the year: “How is that legal?” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com