Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

My first memory in life is of my father moving out. We lived in a two-bedroom apartment on the second floor of a carriage house on a quiet, dead-end lane in Brooklyn Heights. It was 1980, and he was leaving because he’d finally admitted to my mother that he was gay. I watched from the doorway of my room as my dad and a friend of his carried a wide wooden dresser down the stairs. I was two years old, and that moment etched itself in my mind, along with the texture of the apartment’s kitchen floor—white linoleum with little black specks.

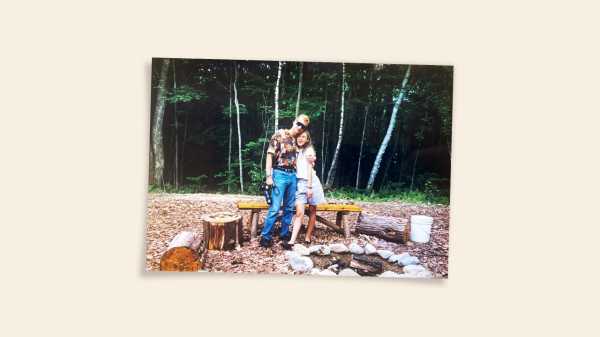

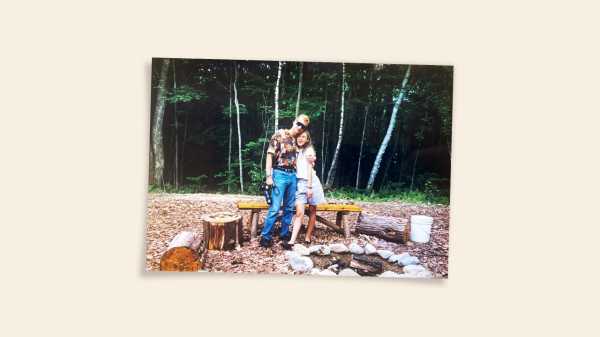

The Last Dance with My Dad

Emily Ziff Griffin on a trip with her father before he died, of AIDS.

My dad eventually settled in the upper half of a brownstone a few blocks away, in a three-story apartment that became the headquarters of an advertising agency my parents started together soon after they separated. I spent Wednesday nights there, along with every other weekend.

After work, my father would come downstairs and prepare a small bowl of Lay’s potato chips, and we would watch “CBS Evening News” with Dan Rather. A story about the hijacking of T.W.A. Flight 847, in which passengers with Jewish-sounding names were isolated and threatened, left me concerned. My father wasn’t religious, but he was Jewish, and so was our last name. “They usually let the women and children go,” my mother assured me later when I suggested I use her German name if I ever got a passport.

After the news, my dad would listen to Ella Fitzgerald and cook dinner—steamed artichokes, maybe roasted fish—and I would play “office” alone at one of the desks upstairs, writing important memos and answering phantom calls. “I’m sorry, he’s not available—can I take a message?” I’d say, satisfied by the smooth click of the phone connecting with its cradle.

My father was a marketing executive who had worked with the Brooklyn Academy of Music in the seventies, before he and my mom started their company. He would often take me to see modern dance in Manhattan. Alvin Ailey, Trisha Brown, and Paul Taylor were all clients, and he took every opportunity to expose me to their work.

Walking through the lobby of City Center was like striding alongside a prince. My dad was tall, handsome, young, and at the height of his creative powers. He dressed in Armani suits and bold neckties that signalled a hint of irreverence. Everyone in the dance world knew him. This was his domain, and I felt important because of who he was. In my regular life, I was terrified that my friends would discover that he was gay, that my family wasn’t like everyone else’s. There in the theatre, the lights would dim, the curtain would rise, the music would start, and my father would take my hand as the dancers took the stage. This was one way we connected. We never learned to discuss hard things, but we shared this liminal space where bodies told stories, and words weren’t necessary.

It was very different at my mother’s house, which was quiet and small, a mere six hundred square feet, and where she often seemed tired, or, as I imagine now, being a mother myself, weighed down by things. On Sunday nights, we watched the detective procedural “Murder, She Wrote.” Unlike in the world chronicled by Dan Rather, in this show, the crime—the problem—was always solved. On Mondays, it was “Kate & Allie,” a sitcom about two divorced moms who share an apartment. Perhaps their story gave my mother comfort as a young woman whose livelihood was still intermingled with the ex-husband who had unceremoniously left her for another man. At the very least, these shows provided enjoyment, and they filled empty space when we didn’t feel like talking.

I found myself looking for normalcy in other people’s real-life families. I would often go to the Millers’ down the street (all names except those belonging to family members have been changed in this story). Their daughter, Callie, was around my age, and, if I slept over on a Saturday night, on Sunday the family would invite me to church, where Callie’s father was an Episcopal reverend. We were not religious ourselves—my father didn’t go to temple and my mother was a Midwestern Protestant who referred to Christians as “God people.” But, even at seven and eight years old, I loved going to church, the smoke of frankincense and organ tones so deep and rich they seemed to vibrate inside my body. There were no surprises there, and I liked being told that God would take care of me.

And then, when I was nine, my mom and I left the neighborhood for a slightly bigger place. We were just a mile or so away, but I quickly drifted apart from Callie and her family. As I moved into adolescence, I longed for the feeling of escape and safety that I had found with them. By then, my father had been diagnosed with AIDS, something I did not feel I could discuss openly with anyone, not even my parents.

In December of 1991, when I was thirteen, I took the train to Baltimore by myself to visit my best friend from sleepaway camp. Samantha Silverman took up space. She played lacrosse, and was opinionated, and seemingly unafraid of boys, and of life. She was also the youngest of three—her older sister was away at college, and her brother Teddy was in high school. Teddy was tall, he played water polo, and he was obsessed with the Red Hot Chili Peppers. I had never heard of the band, but when I went to visit Sam I absolutely pretended I had.

I loved being at their house. Sam’s mother, Carol, worked part time at a local news channel, but she was first and foremost a mom. She’d put a package of Velveeta in the microwave with a jar of salsa and serve it up with a mountain of chips and a direct gaze that said, “Come, sit, be, enjoy.” She wore voluminous cashmere sweaters that draped over her soft middle; hugging her felt like embracing a warm cloud. She was a mom who smiled and giggled. They had money—Sam’s dad was a surgeon—and plush wall-to-wall carpeting and a family room, with a giant L-shaped sofa and a wide-screen TV, where we spent all of our time.

It seemed inevitable by then that my father was going to die. I was still afraid to talk about his illness with anyone, yet it was always there, hulking like a monster’s shadow. At least at Sam’s house, the shadow stayed outside, banished by the delicious snacks and the warm cloud of a mother, by a good friend and her very attractive older brother.

The Chili Peppers’ “Blood Sugar Sex Magik” had been released only a few months earlier, and Teddy would disappear into his room to blast the album while I would think of excuses to talk to him, never mind that he was five years older and had a girlfriend, and that I was basically just a kid.

On New Year’s Eve, the Chili Peppers performed on MTV, all of them shirtless and buff, sweaty with effort. The lead singer, Anthony Kiedis, his long hair swaying behind him, sang “Give It Away,” whose lyrics we (or maybe even more accurately I) interpreted at the time as unabashedly demanding a girl’s virginity. A silver handprint was pressed onto the crotch of his black skater shorts, like a ghostly mark of desire. Watching him, I imagined that Teddy wanted to cradle a bass guitar and feel the thump and hum of the music surround him, to be held by a crowd, to be cheered for, adored.

I don’t remember if it was that night or the next, but at some point I found myself alone with Teddy in the family room. Everyone else had gone to bed. We were watching a movie, and when it ended we decided to watch another. He lay on the floor; I sat on the couch. I pictured him getting up and moving toward me. He would kiss me, and I would let him. We would laugh at the impossibility of it even as it was happening, and I would, in that moment, capture this elusive other life I wanted so badly—one where I was special enough to overcome such barriers as the girlfriend, the age difference, the “sister’s friend” status, and, though it was something he didn’t even know about, the gay father with AIDS. I don’t know if Teddy was engaged in a parallel fantasy because I didn’t have the courage to ask, and he never made a move.

The next day, my mother called. My father had been found in his apartment unconscious and was now in the hospital. He was stable, but he couldn’t walk, and he was having trouble speaking. They suspected an infection. They thought he would be O.K., but given the nature of AIDS they weren’t sure. I said nothing about any of this to the Silvermans. Now it seems outrageous and heartbreaking that I felt I needed to keep silent, but at that time many people were afraid to come near an H.I.V.-positive person. The Silvermans might have been angry. They might have been worried. Worse, they might have loved me anyway, and I found it necessary to hide my vast need for their love.

I took the train back to New York and gazed through the window at the bare trees. I felt heat coming through the vents and inhaled the smell of stale coffee drifting down the aisle. I thought about wanting the impossible: Teddy to kiss me, my father to live. There was no overt relationship between the two desires, and yet they seemed to exist in tandem, as though one miracle could make possible the other.

Back in Brooklyn, I went to the local record store and bought “Blood Sugar Sex Magik” on CD. The album was like the tides—throbbing, aggressive tracks like “Suck My Kiss” and “Give It Away” interspersed with softer, more contemplative songs. It sounded like I felt. I wanted to scream into a microphone. I wanted to kiss Teddy Silverman and tell him the truth—that I thought he was hot, and my dad was dying.

That night, I spoke to my father on the phone, the cord wrapped around my fingers like an anchor. His words were slurred, a mix of fear and steadfastness in his voice. He was calling to let me know he was O.K., in spite of how he sounded. I told him that I loved him. I didn’t allow myself to cry.

Later, I looked out my bedroom window at the dark winter sky, the neighborhood asleep as Kiedis’s voice drifted through the air: “It’s hard to believe that there’s nobody out there. . . . ”

Within days, I went back to eighth grade, and my father went to stay with his parents at their home in Rye, New York. My grandparents, Ruth and Solomon, raised my father and his sister in the Bronx, then, as their circumstances improved, moved to Chappaqua, and eventually to Rye, on the other side of Westchester County. Solomon had managed a successful career as a paint distributor, but it was Ruth who had built the majority of their wealth, as an advertising executive.

Their house was grand—two sprawling stories overlooking Long Island Sound, most of it covered in cream carpeting, like at the Silvermans’. The bathrooms smelled like baby powder and old lipstick. It was late January, cold and barren outside. My father had been relegated to a guest room downstairs, far in every sense from the upstairs living spaces where the family would gather on holidays. As the Sound churned silently beyond the windows, he worked on walking again.

My father had been there for a couple of weeks by the time I went to visit. On my first morning, my grandparents and I watched from the hallway outside his room as he slowly made his way up the wide, carpeted staircase. We acted amazed, as if encouraging a toddler’s amble across the floor. When he reached the sixth step and turned to come down, my grandmother said, “Tomorrow it will be seven.” My father’s face fell. Decades later, I understand her comment more as a defense against reality than as an attempt to shame him into progressing faster. She, too, was trying to keep the monster’s shadow at the door.

In any case, my father wanted to return to his own apartment, and within several weeks he was well enough to do so. By then, he was living in a one-bedroom on the Upper West Side of Manhattan—a lifelong goal. When I visited, I slept on a convertible sofa in the living room.

My dad was back home, but he still couldn’t walk. Kaposi’s sarcoma now covered his legs in purple lesions. During the day, he had a nurse named Lester who would lift him in and out of his wheelchair and take him for walks. At night, one of his friends, or sometimes my mother or I, would stay with him. I don’t remember what we did for dinner—I must have helped serve takeout or bake a frozen pizza. I also don’t remember us talking about anything in particular, certainly not about how sick he was.

One night while staying there I was awakened from a deep sleep. My father was calling for me. I stumbled into his room, and he showed me his bedpan, which was full of excrement. He told me to go get surgical gloves from the bathroom, come back and retrieve the pan, and then dump the contents in the toilet, remove the gloves, and wash my hands. His eyes were glassy, his voice soft—he was embarrassed.

I nodded and left his room. I turned on the bathroom light and saw myself in the mirror. Small breasts. Pimples. Long, wavy hair. I was a child and yet not a child. Had I ever even been a kid? I was shaking slightly as my hands reached for the bedpan. I wondered if I could catch AIDS.

Afterward, I went back to the living room. I thought about the Millers and the prayer that they would say at bedtime, which ended, “If I should die before I wake, I pray the Lord my soul to take. . . . ” Those words were supposed to be a safeguard against eternal suffering after death. But what about eternal suffering before death? I didn’t want the Lord to keep my father’s soul. I wanted my father to survive.

I didn’t know, as I lay there in the dark, my hands still damp from washing them, that this would be the last night I would spend in my father’s home. After, my parents concluded it was too much responsibility for me to be there alone, too hard, too risky. They weren’t wrong.

Spring came, and my father got sicker and sicker, more and more frail. School ended, and it was a relief to know that I was heading back to Evergreen, the sleepaway camp in Maine where I had gone every summer for the past five years. It was the same camp that my father had attended when he was young, and I would be there for eight weeks.

The day before I left, my mother and I went to my father’s apartment to spend some time with him. I stood on his right as he lay in bed. His fingernails were longer than they should have been. His hands were skin and bones, nothing like the strong hands I had once held in the dark at City Center. I bent down and kissed his hollow cheek. I told him that I loved him. I told him that I would miss him and would see him when I got back, though there was little doubt in my mind that this was our last goodbye. He kissed me and nodded. Yes, he said. We’ll see each other then. I walked out, past the wide wooden dresser he’d once carried down to the street, and into the stark hallway of his modern doorman building, my mother behind me. The next morning, I went to camp. It wasn’t until I was sitting with Sam Silverman under the pine trees the first night, loons calling on the lake, a campfire crackling against the chill, that I felt I could breathe.

Days passed, and I settled into camp life. I water-skied over the glassy surface of the lake, my legs strong and solid underneath me, the hum of the boat’s engine the only sound. I played tennis, where I raged against the ball, screaming through every shot. I thought about my father, but the sunlight, the familiar routines, and a crush I was developing on a boy named Ben Goodstein kept the dark shadows away.

On the morning of Saturday, July 4th, I woke up in my cabin, which I shared with Sam, two other girls, and a counsellor. It was drizzling. The five of us got dressed, brushed our teeth, and hurried to breakfast in our ponchos and duck boots. Halfway through the otherwise unremarkable meal, Lynn, the camp director, came to our table and told me that she needed to see me after breakfast.

A weird electric wave spread through me. I knew what this meant. I looked at Sam. “You have to come with me,” I said. But she had no idea why Lynn wanted to see me, no idea that seven months earlier I had left her family’s home in Baltimore while my father was being admitted to the hospital. In some ways, she had no idea who I really was.

When Lynn returned, at the end of the meal, I asked if Sam could come with me, but Lynn said that she needed to speak to me alone. I followed her out the side entrance of the dining hall, across the grass, to the bungalow she shared with her husband, Bill. I glanced at the wood structures that dotted the path: the sailing shed, the other cabins. How long had they stood there? The camp had been in Lynn’s family for decades. My dad had been a camper, then worked there, building the radio station and heading up the theatre program. He and Lynn were the same age; they had been friends. Were these buildings here when they were kids? Had my father walked this exact path before me?

We entered Lynn’s cabin, where Bill was waiting for us, and we all sat down. “I think I know what this is,” I said. Bill told me that my father had died that morning. I didn’t think about it at the time, but my dad’s death was a loss for Lynn, too. Bill said that I should call my mother.

I went to the phone in the next room. The windows faced the lake. No longer bright and blue under the shining sun, it was almost black now, as clouds twisted overhead. I dialled my father’s number. My mom answered. Her voice was high and bright with emotion. She said that everyone was there—my father’s parents, his sister, his long-distance boyfriend, and his best friend. She said that they thought he was gone the night before, but he wasn’t. “He waited for the Fourth,” she said, “so there would be fireworks.” That was very him, I thought. He had always had a sense of occasion.

And then my mother asked me, “Do you want to come home?”

Though I had known on some level that my father would not survive my two months away, I hadn’t considered what would actually happen when he died. I had made no plan. My mother said that my aunt was adamant that I come home, that I would regret it for the rest of my life if I didn’t. But my mom had once told me that when I was born, after the chaos of delivery had passed and she was alone with me in her arms, she had looked down at my face and said, “You are not my property.” I was a child, yes, but I was also my own person, capable of making my own decisions about my life. So what did I want to do?

I pictured myself surrounded by adults with tearstained faces. They’d squeeze my shoulders and leave lipstick marks on my cheeks. Worse, some might be hysterical, and everyone would be looking at me. That poor girl, they’d be thinking, as they watched to see what I would do, what I had to say. I didn’t have anything to say. I wanted to be with my friends and smell the pine trees overhead and feel the crunch of gravel under my feet on the way to the dining hall.

“I want to stay at camp,” I told my mother.

“O.K.,” she said.

To this day, being able to stay at camp is one of the greatest gifts my mother ever gave me. My father’s illness had made everything about my life feel abnormal. I didn’t want to go back to that, not yet.

Though Lynn and Bill knew the truth, we told my cabinmates that my dad had died of cancer. It seemed easier that way, safer. Everyone looked at the floor; none of us had any idea what else to say.

Because it was raining, there was bingo in the dining hall. I went, but because my dad had just died I didn’t have to play. I sat alone on the upper level watching the other campers play below me. The drone of letters and numbers being called filled the spaces between my thoughts: He’s gone. Gone where? Should I be crying? I didn’t want people’s pity.

I got up and went outside. I walked down to the lake. My father used to swim in this water. I pictured him in the distance as a boy, his arms gliding like oars, his legs kicking to keep him afloat. I thought about him in his apartment where I’d left him, in the bed across from the wide wooden dresser. I looked to the sky. I wanted a bolt of lightning. A bird. I wanted my father to appear, glowing like a saint. I wanted him to tell me that everything would be all right, that he was still with me. A row of Sunfish sailboats rattled against their moorings. I could feel the kids inside looking at me through the dining-hall windows. I went back inside.

After lunch, I found Ben. I told him that my dad had died that morning. He looked confused, then concerned. He reached forward and hugged me. “I’m sorry,” he said. I said that it was O.K., the way you might after you accidentally dropped a sandwich on the ground, like, It sucks but, hey, that’s the way it goes sometimes.

That night was the Fourth of July carnival. Everyone dressed in red, white, and blue, and went down to a clearing by the lake where games had been set up. We were given paper tickets that could be used for throwing a whipped-cream pie at a counsellor, or swinging a sledgehammer like an axe to ring a bell. There was the buzz of girls gossiping, the hoots and hollers of prize-winning kids. The tug of Sam’s hand on my arm—Let’s go here, now there—meant that I could be like every other kid that night. I could run, play, laugh. I could whisper about the guy coming toward her, or about how good Ben looked in his chambray button-down and jeans. I could put aside everything except what was right in front of me.

At the end of the carnival, we all headed to the lakefront for fireworks. Fireworks. My mom’s words rocketed through my mind as I sat down on the damp ground. My father waited for this. The show was for him, and my being there, watching it, meant that we were together. I sat, with Sam Silverman on one side, and Ben Goodstein holding my hand on the other, looking out at the water as the first bloom of sparkling light erupted overhead. I heard the Chili Peppers in my head: “The stare she bares cut me / I don’t care, you see, so what if I bleed?” What if I had told my father a real goodbye? What if I had told everyone the truth? What if I had let people see me cry?

I had entered an alternate reality, not like the one found in a chapel or in the rooms of someone else’s house. One that was real—indelible and mine. One in which there was loss, yes, but there was also light bursting in the sky. There was a hand in mine. There was my mother back at home, honoring my father in the way that he deserved. There was my grandmother, Ruth, telling the stories of her son’s young life. And somewhere there was music, a curtain rising, and dancers ready to take the stage. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com