Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Rachel Syme

Staff writer

You’re reading the Goings On newsletter, a guide to what we’re watching, listening to, and doing this week. Sign up to receive it in your in-box.

In the summer of 2022, I visited the Netflix headquarters to report a Profile of the company’s chief content officer, Bela Bajaria, whose big mission at the streamer involves bringing in gobs of international and reality-television projects in order to keep the coffers perennially stocked with snackable “content.” I attended a meeting with Bajaria and Netflix’s unscripted team, in which staffers discussed the upcoming “Squid Game” reality spinoff. The show—inspired by the megahit Korean battle-royale drama of the same name—would echo the original, in that four hundred and fifty-six contestants compete for a 4.56-million-dollar prize through a series of children’s games. The big difference with the reality version, one executive joked, was that the contestants would not be murdered upon elimination from the game. (“There’s life-or-death decisions, but we want to do all that without, you know, the death,” she said.) Even in the pursuit of ultrabingeable spectacles, there are limits.

Knowing how the content sausage gets extruded, you could forgive me for feeling a bit cynical about “Squid Game: The Challenge” when I saw that preview screeners had arrived in my in-box. And yet I pressed Play, prepared to see what people were willing to do to win what has been touted as the biggest jackpot in reality-show history. As it turns out, people will turn themselves completely inside out. They will make moral compromises, sell out friends and family members, shot-put allies straight under the bus.

“Squid Game: The Challenge.”

Photograph courtesy Netflix

Anyone familiar with “Squid Game” will not find too many surprises in the challenges themselves—the contestants live in a creepy warehouse facility very similar to the one in the original show, and compete in similar playground games, such as Red Light Green Light, dismantling delicate Dalgona honeycomb candies, and shooting marbles. But what shocked me was the strange brutality of the proceedings, despite the lowered stakes: when a contestant is eliminated, an ink-filled squib explodes on their chest, and they must slowly crumple to the ground as if they’d actually just been shot. (I would love to have been in the meetings in which they were told to do that.) These “deaths” are often poignant—bosom friends one day go head to head the next. And there is something profoundly unsettling about the desperation that drives hundreds of people to grind their heels into one another’s faces in pursuit of a payday—this is life-changing money, but it is wild to see how many people are willing to change themselves to grab at it. The show pushes contestants to fits of screaming, wailing, and throwing up. In light of a recent exposé about torturous conditions on the set (contestants say they were freezing, food deprived, and robbed of all sense of outside weather or time), the queasiness feels warranted. The squib assassinations may be fake, but the pain is very real. Whether you find this entertaining or stomach-turning is up to you.

Spotlight

Photograph by Pari Dukovic for The New YorkerArt

“Women Dressing Women,” which opens at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute on Dec. 7, was intended to début in 2020, as a sartorial complement to centennial celebrations of women’s suffrage—but the pandemic got in the way. It’s well worth the three-year wait. Fashion is an art form that relies on both women’s labor and women’s dollars to persist, and yet the work of female designers—who, it stands to reason, have the most intimate knowledge of the female form—has regularly gone unheralded. This show is a clear attempt at a corrective: the exhibit highlights the work of mid-nineteenth-century dressmakers, such as Olympe Boisse, along with twentieth-century mavericks like Claire McCardell and more contemporary names, including Marine Serre, Hillary Taymour, Betsey Johnson (whose design is pictured), and Iris van Herpen. The over-all effect—sumptuous, sensual, surprising—makes a powerful argument for fully overhauling the design canon: women have, indeed, always been in fashion.—Rachel Syme

About Town

Dance

Since the dawn of history, humans have chosen to move in unison, often synchronized to a beat. The sources and the consequences of this compulsion are explored in “The March,” a three-part, in-the-round show by Big Dance Theatre. Annie-B Parson, the group’s director, shares choreographer duties with the veteran dancemaker Donna Uchizono and the up-and-coming artist Tendayi Kuumba, a standout performer in Parson’s work for David Byrne’s “American Utopia.” Each choreographer offers a separate take, presenting a different perspective and sensibility, emphasizing form, sensation, or politics.—Brian Seibert (PAC NYC; Dec. 10-16.)

Classical Music

Starting on Dec. 25, 1734, the burghers of Leipzig could have seen Bach conduct his “Christmas Oratorio,” in what was likely its sole performance during the composer’s lifetime. It might not have been the only time that they heard the music, though: Bach was a busy professional, and he cheerfully transmogrified pieces he’d written for local secular celebrations to fit other occasions. Standing in for the great Kapellmeister, Bernard Labadie directs the Orchestra of St. Luke’s and La Chapelle de Québec chamber choir in a performance of the piece, which starts with drums and flurries of snow and ends with the adoration of the Magi.—Fergus McIntosh (Carnegie Hall; Dec. 7.)

Electronic Dance Music

Photograph by Gareth McConnell for The New Yorker

As the front person for the indie-pop band the xx, the singer and guitarist Romy Madley Croft has lent a bashfulness to the group’s minimalist songs. In September, as Romy, she released an absorbing solo début, “Mid Air,” coming out of the quiet and venturing onto the dance floor. Working alongside a few of electronic music’s most imaginative artists—Fred again and Stuart Price, in addition to Brian Eno, Avalon Emerson, and Croft’s bandmate Jamie xx—she conjures strobing, intoxicating grooves of longing and connection. “Dance with me, shoulder to shoulder,” she sings on “Loveher.” “Never in the world have two others been closer than us.”—Sheldon Pearce (Webster Hall; Dec. 7.)

Art

The clean, the gross, the spiritual, and the mercantile, found in both galleries and spas: these are the key ingredients for the young artist Ilana Harris-Babou’s show “Needy Machines,” an often ingenious set of variations on the clichés of wellness culture. For every health- or beauty-related object, there is some free-associative pun-object: for the ceramic screw-top bottle of nail polish in “Confetti 2,” for example, a cast of an actual screw. The video piece “Needy Machine” (2023) is a first-rate joke: one moment, you’re frowning over a glossary of medical terms flashing across the screen; the next, the glossary is gone and you’re left giving your own reflection the stink eye, as though your body is an annoyance in need of fixing. Harris-Babou may suggest that today’s private spiritual questing is tomorrow’s preening, but she’s too interested in her subject to settle for cheap shots.—Jackson Arn (Reviewed in our issue of 12/4/23.) (Candice Madey; through Dec. 16.)

Off Broadway

Photograph by Joan Marcus

In “Hell’s Kitchen,” Alicia Keys smoothes her complex R. & B. catalogue and her spiky teen-age relationships into a musical that’s half coming-of-age fable, half glossy advertisement for nineteen-nineties New York—staged, not coincidentally, by the director of “Rent,” Michael Greif. (Cue “Empire State of Mind” and cargo pants.) Maleah Joi Moon plays the Alicia-counterpart at seventeen; Shoshana Bean is her protective mom; Kecia Lewis is her piano teacher, wise about grief; Brandon Victor Dixon is her undedicated dad. The show’s stunning vocal casting succeeds even when Kristoffer Diaz’s repetitive script falters. Moon’s soaring, Broadway-ready tone already rasps a little; Bean’s blues notes have a similar, fractured quality—and a whole mother-daughter relationship is contained in the singers’ two approaches to making beauty out of strain.—Helen Shaw (Public Theatre; through Jan. 14.)

Movies

Alongside awards-friendly features, late fall offers a batch of noteworthy documentaries, including Jialing Zhang’s “Total Trust,” which relies on clandestinely shot footage to reveal the Chinese government’s use of massive high-tech networks as part of its repression of dissent. The film is centered on several civil-rights lawyers who have been imprisoned for representing people charged with political offenses, such as a journalist arrested for her reporting on sexual abuse by officials. The stories reflect both old-fashioned authoritarian measures—including surveillance, arbitrary arrest, and torture—and the power of systems like a facial-recognition program that blocks citizens from social media and even from travelling. The story, as Zhang tells it, has, for now, no ending at all.—Richard Brody (Opening Dec. 8 at Film Forum.)

Pick Three

The staff writer Sarah Larson shares current obsessions.

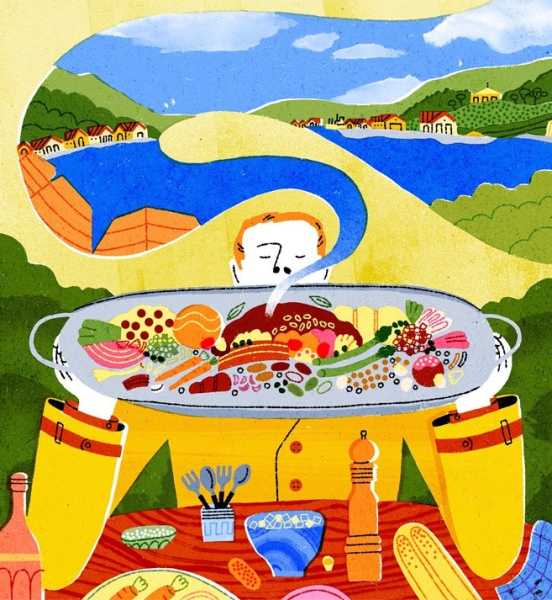

1. My utter lack of interest in making gravlax, cardamom ice cream, musk ox with cloudberries, or reindeer meatballs somehow only enhances my love of the plein-air wonder “New Scandinavian Cooking,” on PBS and streaming, in which the delightful Andreas Viestad zips around Norway and prepares food in front of gorgeous vistas: fjords, birch forests, mountaintops. The energetic Viestad is prone to earnest declarations like “If I were to have a tattoo, it would say, simply, ‘duck fat.’ ”

2. This year, the photographer, director, and indie-rock musician Naomi Yang (of Galaxie 500 and Damon & Naomi) released “Never Be a Punching Bag for Nobody,” an artful documentary centered on an old-school boxing gym in East Boston. Its title, a motto of the gym’s sage proprietor, touches on its narrative strands—East Boston’s colorful history, the residents’ struggles with their behemoth neighbor Logan Airport, and Yang’s learning to box. It’s a luminous meditation on power—personal, political, pugilistic—scored by Yang’s dreamy original soundtrack.

Illustration by Lorena Spurio

3. Liz Phair’s current tour of the immortal “Exile in Guyville,” from 1993, gives us another opportunity to appreciate and argue about her œuvre. Since the release of her 2021 album, “Soberish,” I’ve been urging skeptics rattled by Phair’s 2003 pivot popward to give it a whirl. “Soberish” brings the pleasures of her first few albums—humor, honesty, heart, hooks—to the material of middle age, and the results are enjoyable as hell, without the tinge of nostalgia. Lyrics such as “Dosage is everything / It hurts you or it helps” really hit the spot in one’s pharmaceutical years.

P.S. Good stuff on the Internet:

- Caity Weaver’s profile of the actor Stephanie Courtney (Flo from Progressive)

- Inside the NFL’s Ping-Pong Wars

- “Your 2023 WebMD Wrapped”

An earlier version of this article misspelled Bernard Labadie’s name.

Sourse: newyorker.com