Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In observational documentaries, one important thing tends to be left unspoken: namely, why the films’ subjects let filmmakers embed in their lives. Without knowing what kind of visibility and emotional payoff subjects expected in exchange for granting access, it’s hard to judge how what’s onscreen may have been distorted by the nature of the bargain struck. In Michael Roemer’s extraordinary 1976 documentary, “Dying,” the transaction is built into the story, and the resulting drama is varied, nuanced, and startling. “Dying,” which opens January 24th at Film Forum in a new restoration, follows three terminally ill people in the Boston area through their final decline, and the bond between Roemer and his subjects isn’t transactional but sacramental. The three patients whose lives he enters and records are putting their testaments on film, bequeathing to him and to the world their experiences of the universal homestretch.

The three segments are discrete but composed and sequenced so as to form a dramatic arc as coherent as a work of fiction. (“Dying” was acclaimed in Time when it was broadcast in 1976, and the published report is a prime source of contextual information.) The film exhibits a Shaker-like spareness: no effects, no superimposed titles to identify people or places, no added musical score, just a plain and abrupt editing style that trusts viewers to grasp connections and consequences. It begins with a forty-six-year-old woman named Sally, who tells of having brain cancer that “grows just like moss.” Her head is shaved and her left side paralyzed; as she lies in a hospital bed, a pair of nurses struggle to put her left leg into a brace and the left lens of her glasses is darkened with a taped-on patch. It’s only when Sally is seen from above that a large divot on the right side of her head is revealed.

Neither Roemer nor his participants shrink from the physical burdens and the medical complications that disease and treatment entail, but the movie’s emphasis is on the emotional element of confronting one’s own imminent death. Sally laments her infirmity, recalling earlier days of intense activity, including mountaineering, but she also says that she has no fear. She sees what is coming as a peculiar inevitability akin to seeing a baby and imagining its eventual future as an old man or woman, and her main concern is not to linger unconscious as a “vegetable.” When she is beyond treatment, she returns home to be cared for by her elderly mother, and their days pass with a methodical calm that belies the gravity of her condition. Her death, on June 24, 1975 (announced in a title card), is an anticlimax, as if closing a door after she’d already left.

Roemer, who’s ninety-seven, made documentaries for television in the nineteen-fifties and sixties and directed two of the best of all independent dramas, “Nothing But a Man” (1964) and “The Plot Against Harry” (made in 1969 but not commercially released until 1990). He brings a sure dramatic touch to “Dying” and, thanks to the cinematographer, David Grubin, a camera style that fixes on the participants with restrained astonishment and unflagging devotion. Roemer’s sense of empathy reaches wild extremes in the film’s second part, which he shrewdly labels “Harriet and Bill.” They’re a married couple and, though only one of them, Bill, is dying (of melanoma, at the age of thirty-three), his wife’s suffering is featured just as prominently. They are raising two sons, eight and ten, and Harriet is having trouble doing so amid the stress of coping with Bill’s illness. She’s in emotional overload from the first moment she’s onscreen, sitting in a waiting room with Bill. He tries to sustain normalcy by asking her about her plans for the week; Harriet responds with a sarcastic joke about her plans to go out every night with her many boyfriends, until her bitter laughter dissolves into tears.

She keeps up the same kind of agitated banter when the family goes for a swim in a river, joking that she’ll be hitching a ride from the next motorboat that passes, whoever’s in it. Later, in a discussion with a man who seems to be a psychologist, she admits that Bill’s health is straining their marriage—and that she wishes Bill would die soon, so that she could quickly remarry and provide her sons with another father before their teen years. Bill soon appears with a scar on his forehead and a partially shaved head that he covers with a toupee. When he returns to the hospital, Harriet is home with the children and frazzled. he later tells him about the chaos resulting from one son’s misbehavior, adding, with an oddly callous pathos, “The longer that this is dragged out, the worse it’s gonna get on all of us.” Bill plaintively responds, “Well, what do you want me to do?” She tells another doctor what she wants, admitting to praying that the chemotherapy wouldn’t work.

The sequence of Harriet and Bill, though only twenty-four minutes long, sketches depths of torment latent in family life with a nerve-jangling power to match dramatic films by Nicholas Ray. It’s topped off with a moment the equal of any fiction, in which Harriet bursts out with laughter in front of Bill (framed in an indelibly contrapuntal image) and unleashes unbearably mixed emotions that should have won her an Emmy—and that Roemer embraced with his own blend of compassion and terror. Roemer’s direction may resemble that of such observational filmmakers as Frederick Wiseman (who, famously, avoids showing himself interacting with his subjects), but where Wiseman puts himself into his movies like a virtual visual narrator providing an ongoing analysis of the intellectual and social systems revealed in the action, Roemer turns observation into unrelenting and harrowing emotional immediacy.

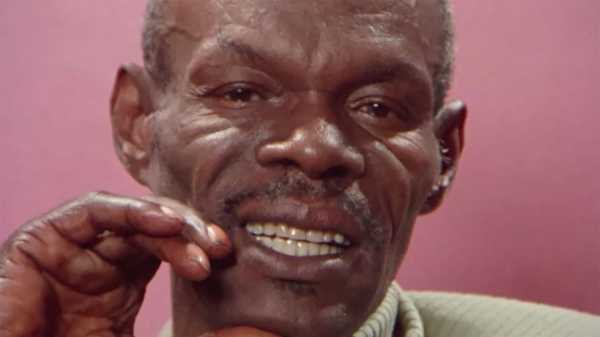

In the third section, “Rev. Bryant,” Roemer indeed puts a family drama in a wider social context, one that makes way for greater amplitude of feeling. The families in the first two parts are white; Bryant and his family are Black, and he’s the minister to a predominantly Black Baptist congregation. At the outset, Bryant, who’s fifty-six, and his wife, Kathleen, are in a doctor’s office. After examining Bryant, the doctor declares that his cancer has spread to his liver and is untreatable. At first, Bryant reels as if from a blow, but he quickly pulls himself together and, in the ride home, he and his wife scoff at the prideful wisdom of medical science as compared with faith. At home, joined by children and grandchildren, Bryant remains mild and cheerful, teaching a child to say grace, and he takes the family on a waterfront outing. In the pulpit, he unleashes before his parishioners an enthusiastic whirlwind of Biblical storytelling and musical fervor.

Bryant speaks directly to Roemer’s camera about growing up a foster child and enduring solitude until meeting Kathleen and having a family of his own. He remains strong enough to take his family on a road trip to the South, to see one last time the places of his youth, and to revisit his ancestors in a graveyard that turns out to be in a state of emblematic neglect. Bryant’s life is a well populated one, overflowing with a communion of past, present, and future, and his final decline, depicted at pain-filled length, is mollified by the loving attention of his wife, his children, and his grandchildren. The movie’s first two parts, of Sally and of Harriet and Bill, end with the title cards announcing the date of the patients’ death. But, pointedly, after a card announces Reverend Bryant’s death, on January 23, 1975, the sequence continues to the memorial service held at his church. The procession of mourners—rather, celebrants, many conveying their love directly to Bryant, who’s in an open casket—shows the clergyman uniting his family and his community in death as he’d done in life. The notion of the spirit living on can feel clichéd, but Roemer’s stirring vision of the civic power of faith renews it and celebrates an everyday, secular form of immortality. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com