Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Not long after she moved to Lisbon with her partner and their son, Kate Friend, a British photographer, learned that Pope Francis would soon make a visit. Friend grew up in what she understood to be a post-religious age. When she was seven or eight, she and her older brother refused to go to Sunday school. As an adult, Friend lived and worked abroad extensively, witnessing faith in many forms, most memorably in parts of Asia, but religion always seemed somewhat exotic, or like something that other people did. In Portugal, the impending arrival of the Pope, in the summer of 2023, revealed a living, believing European society all around her. “It was sort of palpable. This thing is happening,” Friend told me. “I started just going into churches and realizing that everyone was having this very different experience to me.”

Friend’s previous project, “As Chosen By . . .,” had been a series of jewel-like portraits of flowers, selected by notable artists, designers, and other creative spirits. (Ai Weiwei chose “Mother of Thousands,” a crimson-blooming succulent.) She now found herself pondering another series, this time involving wildflowers and holy ground. She was drawn to the necessary optimism of pilgrimage, a state of mind that she recognized from the practice of photography. “It does feel like a sense of optimism and faith and hope that you’re going to come back with something,” Friend said. “You have to believe that there is a picture there. Otherwise you’re not going to go.”

“Marigold, Notre-Dame du Laus,” July, 2024.

Friend shoots on film and in natural light. She made the forty-one botanical portraits as part of “As Chosen By . . . ,” mostly in people’s homes or studios. For her new project, which is called “There Are Always Flowers for Those Who Want to See Them,” she required new constraints and new equipment. “I am drawn to order,” she said. “I like the idea of it, but I also know it’s an unattainable goal.” Friend researched the sixteen Vatican-approved Marian-apparition sites—places where the Virgin Mary has been deemed by the Catholic Church to have shown herself—looking for patches of earth where flowers might grow. “I thought a lot about power and influence and land that millions of people were going over every year, and just thinking about whether that could affect the flower, or me, or the experience in any way,” she said.

“Morning glory, Fátima, Portugal,” May, 2024.

“Astrantia, Notre-Dame du Laus, France,” July, 2024.

Fourteen of the apparition sites are in Europe. (Seeing Mary was a mid-nineteenth-century phenomenon: eight of her appearances took place between 1830 and 1885.) Friend began to spend time in Fátima, about an hour and a half north of Lisbon, where, in 1917, three children saw a woman “brighter than the sun” no fewer than six times, causing a sensation. Friend works alone, and she felt like an early landscape photographer, lugging her equipment in a small trolley, under the sun, into the woods. To shoot the flowers, Friend commissioned a portable studio—she called it a reliquary—with six colored backdrops, for the liturgical colors of the Catholic Church, including green for hope, purple for penance, and red for blood and God’s love. During test shoots, in the early spring of 2024, Friend encountered a number of odd obstacles: her camera failed, her film was damaged by X-ray machines on its way to be processed in London. “I was, like, Is this a sign?” she wondered. “Is this, Turn back now? Or is this some kind of challenge that I need to overcome?” After Friend had her first real success, shooting a gold, brocade-like Ridolfia—a Mediterranean weed, known as false fennel—against a background of deep blue (for Mary) in the woods at Fátima, she lay down on a wall in the sunshine and experienced a feeling of peace.

“Ridolfia, Fátima, Portugal,” May, 2024.

“Scabius, Fátima, Portugal,” May, 2024.

“I don’t want to have a preconceived idea about what is beautiful when I’m making it,” Friend told me on a recent morning in London. She was at Lyndsey Ingram, her gallery, surrounded by the twenty-four pictures in her upcoming show, which opened on April 4th. Some were still in their packaging. Friend’s portraits have a power that comes from the plants themselves. “There’s just so much effort on their part, and they all look so effortless when they come out,” Friend said.

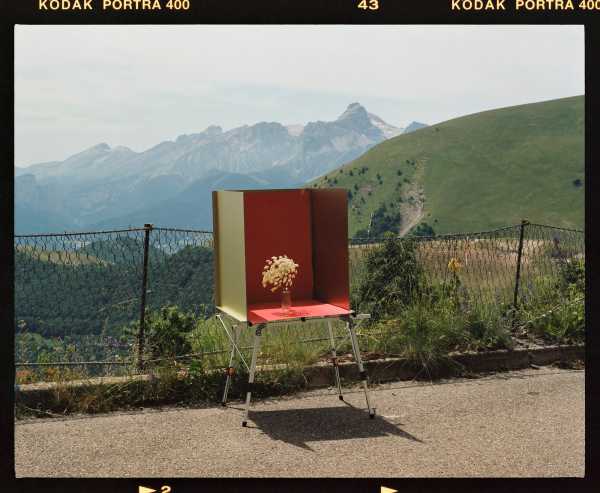

Friend’s portable studio, at La Salette-Fallavaux.

She shot wildflowers at four apparition sites, using a cloth to diffuse a relentless sun, which manifests in the images as a quiet, Godlike beam. Once picked, the flowers are dying. “They don’t last,” Friend said. “Poppies in particular, you’ve got no chance. They’re just going to give up on you after twenty minutes.” I couldn’t stop staring at two fully open scabious flowers that Friend photographed in Fátima, with their dozens of tiny purple-tipped anthers arrayed in expectation. Friend’s gallery show opens with a gold-framed marigold that she spotted growing next to a path at the otherwise uninspiring French apparition site of Notre-Dame du Laus. “There’s a sort of everydayness to it. But then when you look at it, it’s actually incredibly beautifully constructed,” she said. Up close, the marigold has a glowing ruff that is almost decadent. “Papal energy,” Friend calls it.

“Angelica, La Salette Fallavaux, France,” July, 2024.

“Gladiolus, Fátima, Portugal,” May, 2024.

In July, 2024, Friend reached La Salette Fallavaux, a spectacular shrine in the French Alps, ringed with mountains and sky. It had felt essential to include the site in her project. “Can I come back with anything at all?” Friend wondered. “Just anything, and it will feel complete.”

In 1846, while tending their cows, a fourteen-year-old girl and an eleven-year-old boy reported meeting a beautiful lady in a small ravine at La Salette-Fallavaux. The woman was bathed in light and huddled over in grief. She complained of France’s faithlessness. People swore too much. “During Lent, they go to the butcher shop like dogs,” she said. Friend arrived in high summer. The pastures were thick with umbellifers, members of the celery, parsley, and carrot family. Umbellifer means what it sounds like: bearers of shade. It was hot, there were pilgrims, and it was hard to find somewhere secluded to shoot. Friend set up her reliquary in the parking lot. She photographed three white flowers, lit from above, with the consistency of lace. Then she loaded her gear into her rental car, a blue Alfa Romeo. With her camera bag on the passenger seat, she headed back down the mountain road, a steep and dangerous route known as the Laffrey Descent.

On the way up, Friend had passed a resurfacing truck. On the way down, the road was loose with asphalt, “these tiny hot stones,” Friend recalled. Her car began to drift to the right, toward the edge of the tarmac. There was no guardrail, only a grassy slope, falling sharply away. When she pulled the steering wheel, nothing happened. She left the road. “I felt a lot of incredulity as the car tipped,” she said. “Like, I’m not dying here? Now?”

The car rolled over and down until it was held, improbably, by a stand of young trees. The windscreen was smashed but Friend was unhurt. She could think only of the movies—that the car would explode, that the trees would give way—until she heard a man’s voice, in French, telling her to dig her way free. Friend was able to pry open her door and, after grabbing her camera from the passenger seat, clawed into the soil to climb out. She was conscious that a few minutes earlier, she had been engaging with the land and its flowers in a wholly different way. “I remember the feeling of my fingernails, and I remember the determinism to get the most out of there, out of the earth,” she said. She knew that the trees had saved her life. Friend was wearing all white. She staggered up to the road. A pilgrim, who had stopped to help, examined her all over for injuries, found none, and declared her an angel.

“Dahlia, Basilica Parrocchiale di Sant’Andrea delle Fratte, Santuario Madonna del Miracolo, Rome, Italy,” October, 2024.

Friend’s crash, and survival, did not radically recast the project. “I still feel all sorts of things that I probably need to unpack,” she told me. She is open to the idea that she was saved. “I feel like it would be churlish not to be grateful,” she said. “It felt like it was the culmination of multiple tests, all of which were, like, You could turn back now or carry on, and you will find some kind of resolution. And that was the last one and obviously the most intense.” Since her accident, she has found it easier to connect to what is alive in a landscape, in a way that she finds hard to describe but which she understands flowers, in some way, to embody. “They’re the recipients of whatever’s in the earth,” Friend said. “They’ve got this kind of lifeblood in them.” While we were talking, Friend opened the packaging of the photograph that she took that day. It was three stalks of angelica, shot against a horizon of deepening green. Green for life, hope, anticipation. The foremost flower bloomed like a sail. Friend leaned it against the wall. “It is quite a different one from the others,” she said.

Sourse: newyorker.com