Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this storyYou’re reading the Goings On newsletter, a guide to what we’re watching, listening to, and doing this week. Sign up to receive it in your inbox.

The Colombia-born artist Fanny Sanín has lived and worked in New York since 1971, but she has never had a museum survey in the city. Unfortunately, such neglect isn’t unusual for a Latin American woman, but in Sanín’s case it may also be a product of her style: geometric abstraction. She makes colorful, hard-edge compositions of lines and shapes. They’re the kind of paintings that had their heyday in the nineteen-sixties but haven’t been in vogue since (except for the revival of another Latin American woman painter, Carmen Herrera, in the early to mid-two-thousands). Americas Society’s “Fanny Sanín: Geometric Equations” (through July 26), curated by the art historian Edward J. Sullivan, is far from a full-on retrospective, but it’s a great step toward bringing her mesmerizing paintings into wider view.

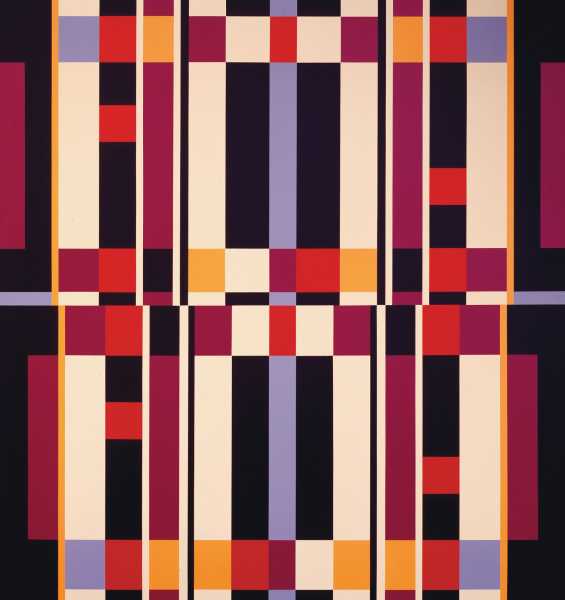

“Acrylic No. 3,” from 1974.Art work by Fanny Sanín; Photograph by William H. Titus

Sanín studied art in Bogotá, Champaign-Urbana, Illinois, and London—and lived in Monterrey, Mexico—before settling in New York. You can trace connections between her work and that of predecessors ranging from Piet Mondrian (Dutch) and Frank Stella (American) to Lygia Clark (Brazilian) and Carlos Rojas (Colombian). But after experimenting briefly with Abstract Expressionism, Sanín developed a painting language that remains entirely her own. You can observe its hallmarks and evolution in this show.

Sanín’s works are all color and form; there’s no white space or perspective, no attempt at optical illusions. She initially focussed on vertical stripes of different widths, then complicated things by introducing rectangles and blockier forms—and, eventually, triangles and diagonals. Her compositions are often symmetrical but rarely simple: paintings such as “Acrylic No. 3” (1974) and “Acrylic No. 1” (2024) keep your eye moving around. Sanín’s palette, especially, is remarkable: she mixes the hues herself, creating hybrid, in-between shades whose appearances are continually surprising within her rigid format.

All this speaks to Sanín’s masterful ability to create harmony out of tension. Her paintings are a delight to look at, with pleasure arising from the complex interplay of colors—say, black against red against orange—or subtle variations in adjoining geometric shapes. It’s no wonder that Sanín makes many preparatory studies, some of which are on display: her work is exacting. But the feat is that it’s also affective—out of meticulousness she creates an abundance of feeling.—Jillian Steinhauer

About Town

Dance

The Mark Morris Dance Group returns to the Joyce for two weeks with two programs, each featuring a première. First comes “You’ve Got to Be Modernistic,” set to rollicking compositions by the stride-piano master James P. Johnson, transcribed, arranged, and played live by Ethan Iverson. In the second week, the mood mellows a little with “Northwest,” set to a suite of Alaskan Indigenous dance songs, adapted for harp and percussion, by John Luther Adams. Both premières are surrounded by variegated repertory gems, from beloved staples like “Going Away Party” to rarer works such as “Silhouettes” and “The Argument.”—Brian Seibert (Joyce Theatre; July 15-26.)

Off Broadway

Jordan Tannahill’s intermittently incredible “Prince Faggot” imagines a future for the British crown, offering its young heir (John McCrea) a gay first love, and—given Shayok Misha Chowdhury’s kink-filled, frequently naked production for Soho Rep—a robust budget for ropes. When the prince brings boyfriend Dev to meet his royal family, their aristocratic inertia threatens the young love. (“You know what your parents are thinking? Shit, we’ve got another Meghan,” Dev says.) Tannahill clearly despises the whole monarchical framing because whenever he can, he has the superb cast turn and talk to us as, seemingly, themselves. Each of these clothed encounters feels far more intimate than the most explicit sex scenes, simply because there’s no generational wealth masquerading as fairy tale getting in the way.—Helen Shaw (Playwrights Horizons; through July 27.)

Hip-Hop

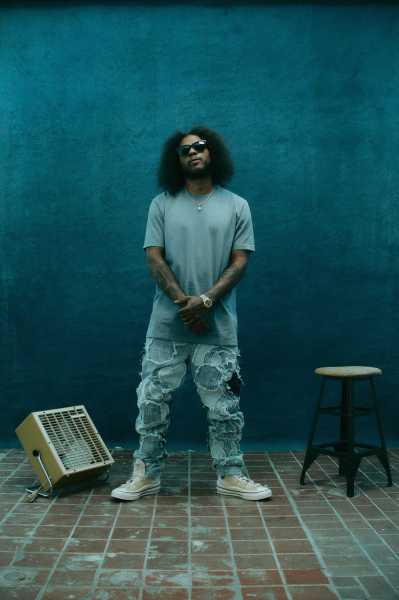

Photograph by John Jay

The independent hip-hop label Top Dawg Entertainment is best known for producing rap’s philosopher-king Kendrick Lamar, the generational R. & B. voice SZA, and the budding phenom Doechii. T.D.E.’s tendrils have spread to Chicago and Chattanooga, but the label was built on a diverse cast of L.A. County lyricists including Carson’s own Ab-Soul. The stargazing artist’s early catalogue fixated on unspooling the mysteries of the universe. The 2012 album “Control System” christened Ab-Soul one of rap’s most far-out thinkers, its third-eye verses forming a galaxy-brain doctrine. On more recent LPs—the self-titled “Herbert” (2022) and “Soul Burger” (2024), an homage to a dead childhood friend—he has become more grounded, focussing his inquisitive mind inward.—Sheldon Pearce (Music Hall of Williamsburg; July 14.)

Classical

The Toomai String Quintet refuses to accept the limited amount of repertoire available to its ensemble type, spotlighting inspired arrangements for five and commissioning new pieces, with a focus on Latin American composers. For an appearance in this year’s Carnegie Hall Citywide series—a bountiful tradition of free concerts across the boroughs—the program boasts arrangements of Villa-Lobos’s engaging “Saudades das selvas brasileiras” (“Longing for the Brazilian forests”); Tania León’s punctuated “Tumbao”; Ernesto Lecuona’s style-bending “Danza lucumí” from Danzas Afro-Cubanas; and more. Other Citywide performances throughout the summer range from the jazz vocalist Cécile McLorin Salvant, in Bryant Park (July 25), to the Symphonic Brass Alliance—a quintet of another kind—on Staten Island (July 26).—Jane Bua (Madison Square Park; July 9.)

Off Broadway

Terry Hu, Louisa Jacobson, and Emmanuelle Mattana in “Trophy Boys.”Photograph by Valerie Terranova

Emmanuelle Mattana’s “Trophy Boys,” a longish seventy-five minutes spent with an élite boys’ high-school debate team, captures the pogo-stick bounce of teens on a deadline: given an hour to build a case that “feminism has failed women,” they ricochet from idiocy (“I love women,” contributes Louisa Jacobson as cool-bro Jared) to rehearsed definitions of intersectionality by team nerd Owen (Mattana herself). The director Danya Taymor flings the drag cast of non-binary and femme performers into dance breaks, seemingly so that Scott (Esco Jouléy) has an excuse to flash his impressive biceps, yearningly, at Jared. When the play gets serious, the tonal shift is nails-on-a-chalkboard painful; before then, the evening is lofted along on a delightful, somehow even more damning esprit de boy.—H.S. (MCC; through July 27.)

Movies

George Hickenlooper and Fax Bahr’s newly restored 1991 documentary “Hearts of Darkness” is based mainly on footage shot and on diaries kept by Eleanor Coppola during the production, in the Philippines, of her husband Francis Ford Coppola’s acclaimed but calamitous Vietnam War drama “Apocalypse Now.” That colossal production, which involved the construction of villages in which to film and the onscreen involvement of the host country’s armed forces, began as a lark and turned into an albatross. Coppola’s struggles with the script, the weather, the cast, and his own perfectionism made the movie go over time and over budget, and the documentary unfolds depressing tales about the chaos of the shoot, which both fuelled the intensity of the performances and overwhelmed the finished film’s drama.—Richard Brody (Film Forum.)

On and Off the Avenue

Rachel Syme on the return of jelly shoes.

Illustration by Sisi Kim

You never forget your first pair of jelly sandals. I got mine when I was thirteen, in the mid-nineties, at a discount-footwear emporium in Albuquerque, called “Shoes on a Shoestring.” Leading up to this acquisition, I’d been begging my mother for months, but kept hitting an impasse: she thought the shoes were ugly and impractical (she was not wrong!), and I insisted that my desire was not about aesthetics or comfort. It was about the fact that everyone else had them, which, as it turns out, is a compelling teen-age-girl tactic: what mother wants to deny her child the chance to fit in, especially if that chance is on deep sale? And so, she caved, and I proudly paraded around the public pool all summer in half-price PVC platforms. They were made of lavender plastic with flecks of silver glitter, smelled like an old inner tube, gave me oozy blisters, and, if I made the mistake of leaving them outside, the straps slightly melted. I never loved a shoe more. Now, if the trend reporters are to be believed, jellies are back. (This was also declared in 2017, then 2021, and again last summer, when The Row released a version, so who knows?) What makes this craze different, perhaps, is that grown women are leading the charge for cheap plastic thrills, shopping their way through an intense nostalgia wave. Jellies—the name alone evokes the winsome wobbliness of childhood—are the closest thing to footwear candy: bright-colored, low-cost, empty-caloried. But the craving is insatiable. Nearly every national retailer has a take: Old Navy sells them, so does J. Crew, Target, ASOS, the Gap, Tuckernuck, Vince, and Zara. There are jelly flats, jelly fisherman sandals, jelly Mary Janes, jelly mules, even jelly sneakers. Endless choices are beckoning; will you cave?

What to Watch

The summer blockbuster “F1”—starring Brad Pitt as an aging Formula One racecar driver, and recently reviewed by our film critic Justin Chang—opens this weekend, so we took this opportunity to ask our colleagues to share their favorite Brad Pitt movie.

I once was at a dinner during which guests tried to recount, from memory, the plot of “Meet Joe Black.” Their recollections amounted to something like: “Brad Pitt has bad bleached hair, eats a lot of peanut butter, briefly speaks in a problematic Jamaican accent, and, also, is Death personified.” Need I say more?—Emma Allen, humor and cartoon editor

“Thelma & Louise” was a breakout role for Pitt, and, though it’s directed by Ridley Scott, the actor is filmed through a female gaze: he’s pure beefcake, a dreamy one-night stand. But those all-American good looks are not to be trusted.—Michael Schulman, staff writer

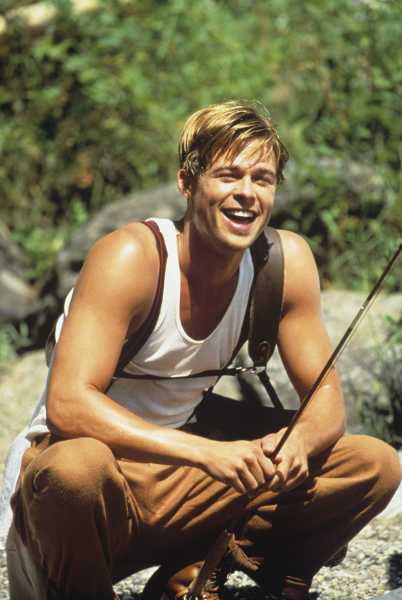

Brad Pitt in “A River Runs Through It” (1991).Photograph by John Kelly / Columbia Pictures / Getty

There is a scene in “A River Runs Through It” that has stayed with me for decades: Pitt’s character, a brilliant young fly fisherman destined for a tragic end, hooks a giant trout in a rushing Montana river, lets it drag him downstream, and disappears underwater, only to end up triumphant, trophy fish in hand, beaming that megawatt smile, his dimples like headlights. In voice-over, the narrator says, “At that moment, I knew, surely and clearly, that I was witnessing perfection.” Few other actors could warrant such apt appraisal.—Rachel Syme, staff writer

“The Tree of Life” is a truly perfect movie—the kind of film that makes you rethink your entire life—and features a perfect performance from Pitt, who plays the strict patriarch of a suburban family in nineteen-fifties Texas. Pitt always seemed more interested in promoting “Moneyball,” a movie that premièred the same year, making me wonder if he fully understood the masterpiece he’d been a part of.—Tyler Foggatt, senior editor

You could make a movie of Pitt eating things in movies, and nowhere is his caloric intake higher and more artful than in “Ocean’s 11,” in which he almost never appears onscreen without nibbling fruit salad, lapping ice cream, slurping shrimp cocktail, or pounding a cheeseburger. I sometimes wonder if George Clooney dared him to create a character using only licks on a lollipop and hand wipes on a napkin. Even his burger-induced burp, in the final scene, is insouciant and cool. It makes you want to burp like that, too.—Zach Helfand, staff writer

P.S. Good stuff on the internet:

- The A.I.-fuelled hive mind

- Gull crime is on the rise

- The elusiveness of a nineties summer

Sourse: newyorker.com