Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Clayton Patterson photographed in his home, on July 6, 2023.Photograph by Noelle Flores Théard / The New Yorker

The artist and folk historian Clayton Patterson has lived in the same storefront home on the Lower East Side for four decades. You can find him holding court in an old upholstered chair just inside the picture window, his signature silver beard flowing down his chest, his head adorned with a custom Clayton Cap decorated with a smiling skull. Patterson, who is seventy-four, has been making art in and about the Lower East Side for so long that its history and his own have become inextricable. A decade ago, he threatened to leave the neighborhood, having grown fed up with the pace of gentrification, the closing of local haunts, the death of beloved friends. The Times declared his departure the end of an era, the exit of “Manhattan’s last bohemian.” But, in the end, Patterson stayed.

A cardboard tank that was built to protest an N.Y.P.D. armored personnel carrier in front of Bullet Space.

A police officer checking up on a seemingly unconscious person.

A public toilet set on fire to protest its neglect.

The legendary bar and music venue CBGB.

A native of Alberta, Canada, Patterson comes from what he described to me recently as the “bad end of the working class.” He left home at the age of fifteen, and spent a decade and a half in various art schools as both a student and a teacher. When, in 1979, he came to the Lower East Side with his partner, the artist Elsa Rensaa, a decade of “benign neglect,” landlord-sponsored arson, and government seizures had left the immigrant enclave pocked with abandoned buildings and discarded needles. But New Yorkers abhor a vacuum, and squatters, artists, and outcasts quickly flocked to the area’s cheap real estate. Patterson began walking the streets with a Pentax 125 S.L.R. that Rensaa had gifted him, taking pictures of the sex workers, poets, schoolchildren, and punks who called the Lower East Side home. The camera became Patterson’s key to the city, taking him places that he might not have otherwise gone: drag-queen and hardcore shows at the Pyramid Club, radical street protests, local landmarks like CBGB and Bullet Space, and art events like one at which the performance artist Roger Kaufmann severed his own finger. Patterson’s photographs served as plainspoken time capsules of the community. In a 2008 documentary called “Captured,” which chronicles his life on the Lower East Side, he says, “Looking out on the street is like being in an aquarium, and when I look out on the street I see this activity all day long.”

Elsa Rensaa, Patterson’s partner and creative collaborator, ready to document street action.

In 1983, Patterson and Rensaa purchased 161 Essex Street, a two-story building that had formerly housed a dressmaker’s shop. To support themselves, they created the Clayton Cap, perhaps the first example of a designer baseball hat, which was released in 1986 and featured embroidery patterns that Rensaa made using repurposed machines sourced from the neighborhood’s rapidly disappearing garment industry. The haberdashery became a runaway hit among artists and celebrities, attracting clients including Jim Dine, David Hockney, Mick Jagger, and the actor Matt Dillon. The same year, Patterson and Rensaa converted their storefront into a gallery, where they’ve exhibited the work of local luminaries such as Genesis P-Orridge, Taylor Mead, Quentin Crisp, and Dash Snow. Patterson transformed the front window of the space into a “Hall of Fame,” featuring a weekly selection of portraits from his series “Wall of Fame,” in which subjects, most of them neighborhood residents, posed for him in front of the gallery’s graffiti-covered front door.

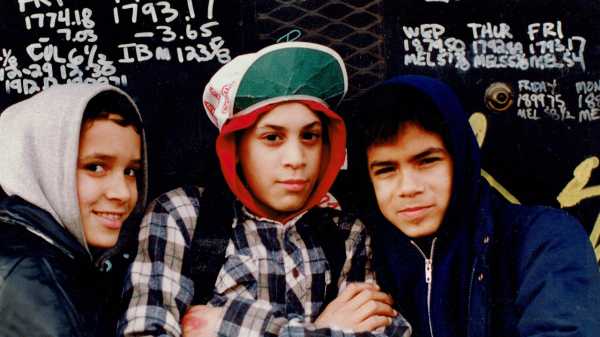

A young boy holds a pet.

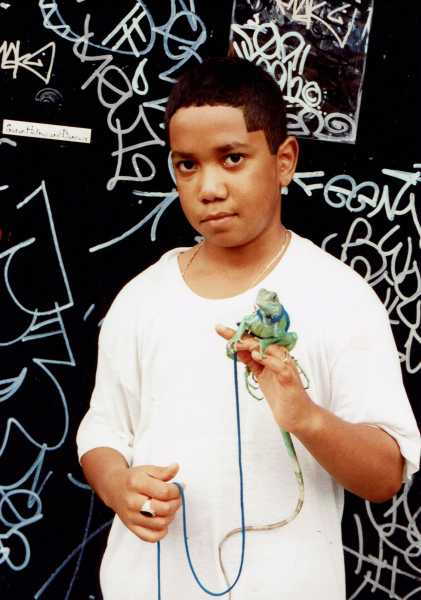

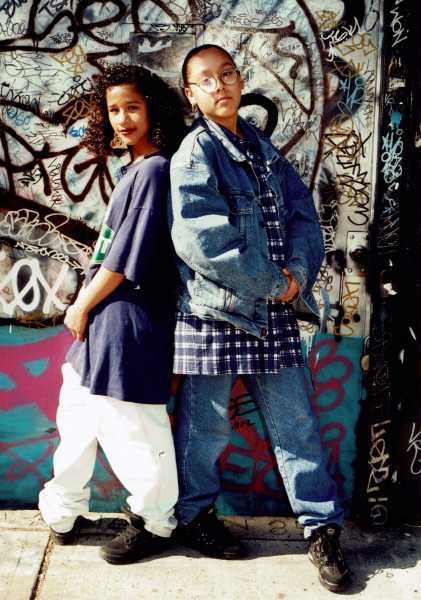

A young woman poses for the camera.

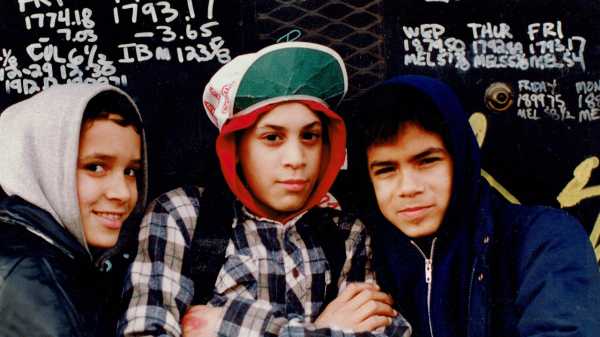

Young people stand on the sidewalk.

The artist Butch Morris.

Essex Street gave Patterson a foothold in the booming eighties art market. But he was turned off by the scene. “It was about competition: making money, being at the Odeon, eating at Mr. Chow’s—being the strongest bull in the pen,” he told me. What he did instead was build a career as the neighborhood’s most dogged archivist. Using the money that he and Rensaa made from selling Clayton Caps, Patterson created the Clayton Archive, a collection of video, art works, books, press clips, and Lower East Side ephemera, including old heroin bags. His body of street photography grew to encompass thousands of images. “I have pictures of people that nobody else has,” he told me. “Maybe they had a fire, maybe they lost their home, maybe they became homeless and everything got lost.” Patterson’s friend Gryphon Rue, who curated a 2021 exhibit of Patterson’s photos at the downtown bookstore and arts space Printed Matter, has said that sifting through the archive “felt like punching holes from inside a cardboard box or digging through the pockets of a ghost. How does one find order in an avalanche of souls?”

The aftermath of a fire on East Ninth Street and Avenue D in the early nineties.

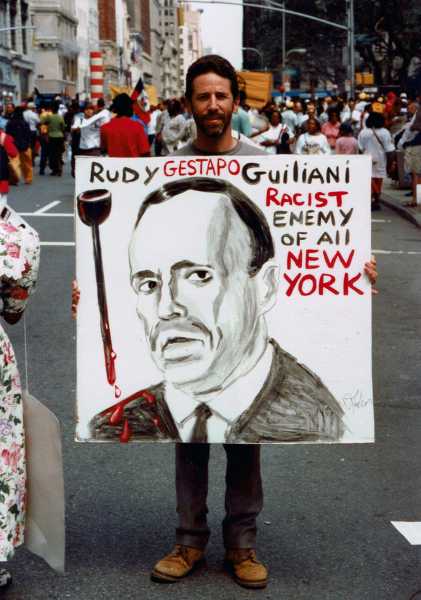

Signs at a protest.

David (Red) Rodriquez attends a demonstration supporting housing for the homeless.

Robert Lederman founded the protest group ARTIST (Artists’ Response To Illegal State Tactics), in 1993.

Over the years, Patterson formed the Tattoo Society of New York, which was instrumental in overturning a citywide ban on the underground art form; published numerous books and anthologies chronicling the Lower East Side; and created the annual N.Y. Acker Awards, to honor the work of experimental artists and activists. But perhaps his most significant role has been as a citizen journalist. In 1988, Patterson was videotaping a performance at the Pyramid Club when the Tompkins Square Park police riot broke out, a few blocks away, after law enforcement tried to clear the park and impose a curfew. Patterson rushed over and began filming the scene, and Rensaa helped smuggle the tapes out of the park for safekeeping. The resulting footage, which aired on the news, captured the N.Y.P.D.’s brutal tactics for suppressing the protest. The Manhattan District Attorney subpoenaed Patterson to turn over the tape, but Patterson refused—and was jailed for contempt of court—until he negotiated a way to retain the rights to his work. He told me, “People see me as a troublemaker, antisocial, anti-government—they see me as an anarchist, but I’m not. I’m an artist.”

A courthouse in the late eighties.

A self-portrait of Patterson seen on a glass window punctured by a rock thrown during an anti-gentrification protest.

Patterson’s video and photography work has been displayed hundreds of times in New York City and beyond. Some of his images are currently installed outdoors as part of the city’s Photoville Festival. But Patterson resists labelling himself a photographer, because his camera is ultimately just one tool behind his decades-long project of preservation. He told me, “My art is not the individual pieces. It’s about the large vision: survival, being and continuing to be creative.”

A police officer photographs Patterson for fun, in the early nineties. Rik Little, of the TV series “The Church of Shooting Yourself,” is seen in the background.

Sourse: newyorker.com