Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The last time I talked to Colman Domingo, in 2021, his life was completely different. At fifty-one, he was a successful character actor, the kind whose face you might recognize from a flashy supporting role on TV—say, a con man turned post-apocalyptic dictator on “Fear the Walking Dead,” or Zendaya’s rehab sponsor on “Euphoria.” After a long career in theatre, appearing in musicals on Broadway and writing and directing Off Broadway, he was popping up in movies—as a pimp in “Zola,” as a creepy laundromat worker in “Candyman”—and on red carpets, where he’d rock a leopard-print or fuchsia suit. But relatively few people knew his name.

Then, in 2022, Domingo won an Emmy, for “Euphoria.” The following year, he had a big, villainous part in the movie musical “The Color Purple” and played the title role in “Rustin,” George C. Wolfe’s bio-pic of the gay civil-rights leader Bayard Rustin. That movie, which had the backing of Netflix and of Barack and Michelle Obama’s outfit Higher Ground, was a high-profile showcase for Domingo’s heart-on-his-sleeve charisma; like Rustin himself, he was finally getting his due. The role earned Domingo an Oscar nomination for Best Actor. Come next weekend, he stands a strong chance of getting a second consecutive nomination in the category, for the A24 drama “Sing Sing.” In other words, Colman Domingo is a movie star now. (In fact, Out called him “the first Black gay movie star,” a title that, with a few possible caveats, is hard to dispute.)

In “Sing Sing,” which returns for a theatrical rerelease this weekend, Domingo plays an innocent man incarcerated at Sing Sing Correctional Facility who has become a leading player in a prison theatrical troupe, part of the nonprofit program Rehabilitation Through the Arts. The film, directed by Greg Kwedar, draws on real life and real people—John (Divine G) Whitfield, the basis for Domingo’s character, is an alumnus of the program, and the cast includes former inmates playing versions of themselves, notably, his co-star Clarence (Divine Eye) Maclin.

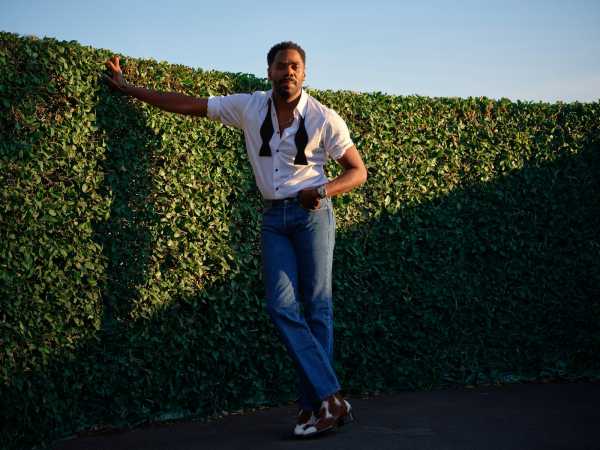

Whereas Divine G makes art in constricted circumstances, Domingo has been living an expansive life. When I caught him last month, over Zoom, he was at his home office in Malibu, where he lives with his husband, Raúl. (Fortunately, the house was unharmed by the wildfires.) He’d just come from London, and before that New York, and before that Puerto Rico, where he’d shot the Netflix series “The Four Seasons,” Tina Fey’s remake of the Alan Alda film. “You’re working with, like, the mad scientists of comedy: Tina Fey, Steve Carell, Will Forte,” he said, with trademark exuberance. “And now introducing the new comedy ingénue . . . Colman Domingo!” Next, he was off to a Mexican getaway with Tessa Thompson and Niecy Nash, and then on to the Golden Globes, where he was nominated for “Sing Sing.” (His look: a Valentino mohair-wool tux with a flowing checkered ribbon tie.) At his desk, he wore an A24 cap and sat in front of framed photographs of Paul Newman and James Baldwin. Occasionally, he got distracted by a squirrel or a piece of chocolate, as we walked the long path that brought him from West Philly to late-blooming stardom. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

When we talked in 2021, I remember not knowing which role to focus on, because you were in four movies at once but not the lead of any of them. Does it feel like your life has completely changed in the past four years?

It has, but I can feel on the inside where it’s been gradual, where I’ve been making strides for a long time. It’s wild. I’ve been working for a good thirty-four years, and I’ve always been forging my own path. One of my early agents said, “You’re a character actor in a leading man’s body, and it’s going to take a while for the industry to understand that you’re actually both.” I always believed that I could lead, but it’s actually very challenging to be a character actor, and that’s where I usually find my joy: in discovery.

But the things that I’ve led, it’s actually because I helped build them. Even “Rustin,” I was a part of building it for four years before it actually happened. And “Sing Sing,” as well. For “Euphoria,” Sam Levenson actually wrote toward me. Directors know my work, writers know my work. They’re like, This guy, he can turn on a dime. He can play a queer civil-rights hero, and then flip and play an abuser in “The Color Purple.” I have this dual thing happening all the time.

I read that you shot “Sing Sing” in the eighteen days between “The Color Purple” and pickups for “Rustin.” What was it like to plunge yourself into this project between two other things that are completely different?

It felt like it had to happen. In anything that I do, if I’m a little nervous and I feel like I might mess it up, that’s where I run toward. Rustin, that’s a seismic role. I was on pretty much every single page of the script. And “The Color Purple,” where I was the male lead—he’s very propulsive, and he changes everyone in the film. And then I have this, where I have to lead with a sense of generosity, to allow people who had never been on a set to do it. But I knew that I was ready for it, because I’ve been ready for thirty-four years. I’ve been the lead of companies in theatres. A lot of things right now are harkening back to my theatre days, things that I’ve been doing that people didn’t know that I’ve been doing. I used to always think, Why do I always have to build it from the ground up? Why can’t things just come to me? But I realize now that that’s part of my journey.

When you say you built “Sing Sing” from the ground up, what did that consist of?

I’ll give you the genesis. My director, Greg Kwedar, and the co-writer, Clint Bentley, had been working at Sing Sing prison as volunteers, and they kept thinking, Wow, if we can make something out of this experience with the Rehabilitation Through the Arts program, it could be profound. They did passes of scripts for a couple years. Six years later, whatever they had they sort of trashed. Then Greg came up with the idea to center on the friendship between these two men, and he thought, Oh, maybe the story’s actually smaller. It’s just about a friendship, while they’re putting on this play and going through their parole-board hearings. He said he wrote my name down on the bottom of the treatment. They reached out to me for a meeting. We had a nice Zoom. I said, “Send me the script.” They said, “We don’t have one. We have an article from Esquire detailing the program.” And I said, “Send me that.” I read it pretty quickly, and I was like, Wow, a program like this exists? And I’m thinking about these beautiful images they had, of these Black and brown men wearing costumes, knowing that they’ve gone through the prison system, and they looked so full of joy.

We started doing Zoom meetings. I would raise questions, offer suggestions and notes, and then eventually we would add in Clarence Maclin. We devised it all together, and the two writers, Greg and Clint, would go back and write and bring us something different. So we got to a very rudimentary draft, I thought, that would be eventually developed and we would shoot it later. But then they were, like, “When can we shoot it?” I was, like, “I don’t have any time! I have about eighteen days between the end of ‘The Color Purple’ and pickups for ‘Rustin’ on the National Mall.” And Clarence Maclin, I’ll never forget it, smiled his big, toothy smile, and said, “C’mon, man, Colman. We can do it!” There was something about that enthusiasm and that raw, unadulterated joy that really affected me.

Your backgrounds are similar in some ways. You’ve both done a lot of theatre, put up shows, built things out of nothing—except that Clarence was doing it in Sing Sing, and you were doing it Off Broadway. But you also had the skill set of working on camera. Were there things that he needed to pick up from you?

Just some small, key things. It’s funny, because, just to prepare for this, I decided to give myself the joy of watching the movie for the second time. I’d only seen a rough cut of it, but I was on a flight and was able to download it. I thought Clarence did such beautiful work. He was like a sponge. He would watch take after take, and sometimes, when he was a bit more theatrical, I would say to him, “That was beautiful, but just dial it in. It’s just you and I and the camera. We don’t have to project.” He goes to these beautiful, intimate moments on camera. It all feels very raw, in a way that I think I needed after doing very large, polished productions like “The Color Purple” and “Rustin”—almost going back to my roots of devising theatre in a black box with five hundred dollars of my own money.

That’s interesting that you just watched it for the first time in a while. What was the experience of watching yourself?

This was the first time on film that I’ve been able to create exactly, without a lot of compromise, the kind of environment that I wanted to build, the level of performance. It feels more, honestly, like me. I know it’s my most raw performance. I realized that that’s what needed to happen. I’m with men who had the lived experience, and they were playing versions of themselves. So who was I not to play a version of myself, which is someone who finds a lot of hope and light in dark spaces?

You also had the real Divine G there. How did you work with him on being yourself but also capturing him?

It wasn’t about just playing him but about building a character who has to be in the center of the storm. So I divorced myself from feeling like I had to actually portray him. But there is some special alchemy that happens when you’re downloading a human being and listening to what they say and having dinners with them. Things come into your psyche. Like, I added a pirouette. We talked about him wanting to be a dancer when he was at the High School for the Performing Arts, and he would have to fight dudes on the way home, so he stopped doing it. I just kept that in my body, like, Oh, I have to keep that dancer alive in there in some way.

I know you’re very big into research, but with this film a lot of that had to get thrown out the window, because it was happening so fast. It must have been a very different process from “Rustin,” which had the weight of all that history.

There’s a film I’m going to do next year, and I have a stack of research books over here. I will build collages sometimes. I will build libraries of information: the time line, the period, what kind of clothes people were wearing, what kind of food was available. All that stuff that no one will ever see, but I will know, because it helps build a whole human being. But, with this process, I had the raw materials of myself. I actually made a choice not to research the prison-industrial complex, because otherwise I thought I would be making something very political. I didn’t want that to affect me. All I wanted to be affected by was: Here is someone who’s been wrongly accused of a crime and is now in prison. I am a Black man in America, and that’s not so far from my reality, you know what I mean? So I had to bring a lot of myself into it.

You’ve described yourself as a very shy kid who was not interested in acting for a long time. Why were you so shy?

I grew up in a household with a lot of gregarious people, and I was the more bookish one. And the one who had a slight speech impediment, which was a lisp. I was very thin. I was not athletic. All those things made me more insular. I grew up in a working-class neighborhood with some tough kids, and you either are a jock or the nerd who always gets picked on. I loved being in the library. I loved books. I loved playing the violin—all those things that were not cool. I didn’t like hanging outside and playing with the other kids, because I didn’t want to get beat up.

How much of your introvertedness had to do with your sexuality?

I don’t think it had anything to do with my sexuality, to be honest. I didn’t even start to understand my sexuality until I got to college. Like, Oh, this is different. I have a crush on this person. I came out when I was twenty-one years old. My family loved me, and I knew that, so it wasn’t this arduous journey. I had already moved to San Francisco, and I came out to my mother on the phone, and she was beyond loving. If I’ve had any struggle in my life, it was never because of family. I’ve always been loved and supported, so that’s how I navigate this industry. There was never a coming-out story. There was always just: I won’t let the industry or the universe dictate what I can and cannot do. When people put “gay” in front of “actor,” it’s weird to me. Do they put “straight actor” in front of Daniel Craig? It’s almost putting up a marker to limit me.

Daniel Craig has played so many gay men now that we should call him “straight actor Daniel Craig.”

To make sure it’s clear?

Yeah. [Domingo laughs.] Your stepfather sanded floors, and your mom worked at a bank. Did they have a relationship with the arts, or did you discover that on your own?

My mother was such a supporter of the arts. We didn’t go to the theatre, we didn’t go to the opera—we couldn’t afford any of that. But we always had music in the house, and my mother loved putting us in summer programs where we could express ourselves. My brother would do beautiful charcoals. My sister would write poetry. And my younger brother is a self-made musician and a producer. But I didn’t realize who we got it from until my mother stood at a funeral, and she delivered these remarks, and I thought, My mother is incredible! She really captivated the audience. I was, like, I get my acting from my mother. I didn’t know that!

I know at one point in New York you performed a one-man show called “A Boy and his Soul.” What kind of Philly soul music did you grow up with?

Oh, I grew up with the Spinners, the Stylistics, Teddy Pendergrass, Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes. I lived next door to two guys who were session musicians for Philadelphia International Records, so they were on all the hit records for Teddy Pendergrass, you name it. Because we had row homes, their wall was right there, so I grew up hearing that music. I’m just seeing these two cool dudes coming and going every so often—big hats, tight pants, bell-bottoms, all that stuff. The way I dress right now, it’s probably because of all that stuff I used to see. They seemed just cool. They were still deeply embedded in inner-city West Philly.

And you went to high school with Will Smith, who was already a rapper, right?

Yeah, he was rapping at the Wynne Ballroom in Philadelphia, he and Jazzy Jeff. They were the cool kids. I went to Overbrook High School—they call it the Castle on the Hill. It’s this beautiful school, and it was filled with the diverse backgrounds of the community. It was mostly Black, and most people who went there were either very upper-middle class or middle class or people who took the bus, like me. Will was in the more upper echelons of society.

Did he know who you were? Were you acquaintances?

No. He dated one of my best friends. That’s how I knew about Will. She would invite me, “Hey, I’m going to the Wynne Ballroom, because Jeff and Will are going to perform.” I wasn’t cool. I didn’t go to things like that. And I didn’t have any money.

It’s amazing to think that two people from your high school went on to be nominated for Best Actor at the Oscars—and one of them got into a brawl.

Yeah, that was an unfortunate moment of his. I’m not a brawler. I’m a lover, not a fighter.

You went to Temple University wanting to be a photojournalist. What kind of photojournalism did you foresee yourself doing?

As a kid, when I watched the news with my mom, I was very concerned about what was happening in the world. I wanted to take pictures of it and show people what’s going on. I really wanted to go to war-torn places. That was thrown a curveball the moment I took an acting class as an elective, and I found another way to tell stories. But, honestly, it does seem to me that I’m doing the exact same thing that I set out to do. It’s just in a different form. Like, I want to tell stories—what is that? [He looks out the window.] I’m sorry, a squirrel just distracted me. Are you eating my plant? [Shoos the squirrel away.] I’ve always had a journalistic heart, in a way. I used to do head shots. I used to do backstage photography. I like being a fly on a wall.

Were there certain photographers who you were into?

I loved Diane Arbus. Gordon Parks is one of my favorites, as well, and also Sanlé Sory. I love the way they capture life and human beings. Richard Avedon as well. He did this collaboration with James Baldwin called “Nothing Personal,” and it’s one of the most stunning books about America in the nineteen-sixties.

When you were taking head shots of actor friends, did you take any head shots for anyone I would know? I’m asking you to name-drop.

Oh, De’Adre Aziza. Eisa Davis. They were my co-stars in “Passing Strange.” I did marry some pretty well-known people, because I’m an officiant, as well. I married Nona Hendryx to her partner, and I married Niecy Nash to her partner. I married Anika Noni Rose, the Disney princess, to her husband. I’ve probably married more famous people than taken their head shots.

What other day jobs did you have?

I have been a baker’s assistant. I have been a waiter. I’ve been a bartender. That was most of my side hustle. I taught. I never had a full-time day job. My jobs were always jobs where I could go in and out. I was also a dancer for bar mitzvahs. I would get, like, Mrs. Rabinowitz up dancing. You’ve been to those? I was one of those people.

Oh, I had one. Actually, Idina Menzel sang at my best friend’s bar mitzvah when we were thirteen, before she was famous.

Oh, but they had celebrity appearances when I was doing them. They upped that game. I was amazed at the money that was spent on these parties. The video projections! The food! It was like a wedding! I was a very good dancer, and if you were a good dancer at one bar mitzvah, your rate went up for the others, because they knew I got the party started.

How would you rate yourself as a bartender?

Excellent. I could make Manhattans and gimlets and things like that. But I started out at bars where it was about making something red, sugary, and really high octane—Alabama Slammers, things like that. Then I moved more into craft-cocktail places. My last bartending gigs were at the West Bank Cafe and the 55 Bar, in New York.

You spent ten years or so in San Francisco after college. What was your life like?

I was liberating myself. I moved there to not only find myself as an artist but also find myself as a man. I grew my hair out a little long. I would go to nude beaches and to places like Harbin Hot Springs. I would chant and go to Buddhist practices, but also Glide Memorial Church. I was drumming with hippie drum circles. My San Francisco sounds like the nineteen-sixties, but it was the nineties. I lived in the Mission District, and the Mission District was perfect for me, because it had a huge lesbian contingent and Latino families.

Was this when Kiki & Herb were starting there?

Yes! Are you kidding me? Justin Bond threw a shoe at me at a performance, and I never felt luckier. Yes, I was there during that time, with Kiki & Herb and all these underground artists, like Connie Champagne and Phillip R. Ford. He would do a drag version of “Valley of the Dolls.” Truly, everything I am as an artist I owe to San Francisco at that time.

What prompted you to move to New York finally?

I was working at all the great places—A.C.T., Berkeley Rep, all the Shakespeare festivals—and I felt like I was starting to get stagnant. I always had a dream to be in the front of the Samuel French scripts, in the original casts. So that had to happen in New York. Always in the front of these books was the Vineyard Theatre, the Public Theatre, you name it. So I moved to New York at thirty-five years old and re-started my career. I didn’t move with any promises of anything. I just thought, I want to take a chance. I was roommates with Norbert Leo Butz’s younger brother Jim Butz. I found a sublet situation with him in Astoria, Queens, these two artists trying to make their way.

The first time I remember seeing you in something was “Passing Strange,” Stew’s autobiographical musical at the Public, in 2007. Was that an important turning point?

I auditioned for that show on July 24th, 2006. Why is that day so very important? Because my mother died the very next day. I was a different person. The day after, I’m in Philadelphia, cleaning out my mother’s apartment, and I got called for a callback. I said, “I’m sorry, I can’t come, because I lost my mother.” And just six months before, my stepfather passed away, so I was truly untethered. They kindly waited to have callbacks for two weeks. I went into the audition, and they asked me to sing a gospel song. I sang this song like I’ve never sung anything in my life. I can look back and say that I was singing for myself. I needed to give words to something. I left that audition and went to the side of the Public Theatre, and I burst into tears. It wasn’t just a gig. I knew I needed this company and this experience. I felt like this was absolutely mine, and then I messed it all up.

And then I got cast. I know for sure, there’s the actor before my parents’ death, and the actor after. I became more attached to the work and less attached to caring what anyone thought about it. I just thought, This is my expression. This is the way I want to tell a story, and the only people that I have to seek approval from are no longer on this earth, so therefore I’m liberated. That changed my life. I did it at Berkeley Rep, and I did a lot of healing there as well. Then we moved to the Public. And then we moved to Broadway. By the time Spike Lee came and filmed the last three performances, it was the first time we were asked to do a reprisal of the song “It’s Alright,” and it took on this aspect of a church revival. It was fury, it was spirit, it was God, it was Allah, it was Buddha. At some point, I’m lying in Stew’s arms like the pietà, singing, “It’s alright,” looking up at the heavens. The three-year journey of that show transformed my entire life.

Is that how you started working with Spike Lee, when he filmed “Passing Strange”?

He first cast me in his film “Miracle at St. Anna.” I had a very small role in that. And then it was “Passing Strange.” Then “Red Hook Summer,” where I’m grateful that I have one of the rare dolly shots.

Even at that point in your career, coming off “Passing Strange,” you’ve said that you would still go back to bartending after a gig. How did you get by emotionally?

I thought that was the life of an artist, you know what I mean? The ebbs and flows were just a part of it. Now, by the time I got into my mid-forties, that was the only time I thought, Is this making sense? I started to look at what’s ahead of me. It was when I came back from London doing “The Scottsboro Boys.” You can’t do a show like “The Scottsboro Boys” and come back and suddenly go for some bullshit roles on television. So I was very frustrated when I came back, and there was this merry-go-round of pilot season and auditioning, and I thought, This is going to kill me. I can’t do this anymore. I started to question that thing that I knew to be true. I don’t have an ego about this, but I know that I’m talented, and I know that I have purpose and intention. But, a lot of times, that’s not sexy, and that doesn’t move you forward.

Was there a final straw, some rejection that made you feel like you might actually need to stop?

Oh, yeah. [He picks up a chocolate bar on his desk.] Where did this chocolate bar come from? I think my assistant left it here. “Movie Chocolate: Fizzy Fountain Soda.” Nice! Yeah, there was a moment. I was auditioning literally eight times a week. I was exhausted. And I was bartending. Things weren’t working well. The auditions I got, I just felt like they were not leaning toward my talent. And there was this audition for a recurring role on “Boardwalk Empire.” This role seemed tailor-made for me. They said, It’s a song-and-dance man—he’s the m.c. of this cabaret. I danced, I wore a tuxedo, I sang. And the casting director was, like, “Oh, my God, perfect.” They sent my tape to producers. Anyway, I’m at the gym, and my agent calls me up, and I thought, O.K., here’s something. I’m going to book something. I need to book something. And she said, “I got a call from ‘Boardwalk Empire.’ They loved you.” Usually, that’s a good sign, right? She said, “But then a researcher piped in and said, ‘Well, you know, the m.c.s of those clubs were fair-skinned back in the day.’ ”

And I lost my mind. I screamed, “They knew what I looked like before I got there! I feel like everyone’s fucking with me!” And this is in a gym. I literally burst into tears. Everyone’s looking at me. I go to the corner; I’m sobbing. I said, “I can’t take it. This is going to kill me.” And I left the gym, walked home, went into my apartment at Manhattan Plaza, the home for wayward actors, on Forty-Third and Ninth, and I sat down with my husband. I said, “Would you be disappointed if I stopped doing this, as of today?” He said, “I’ll do whatever you want. If you want to leave New York, we can leave New York, too.” And I started to put things in place to say, “I’m out.” I had my head-shot business as a side hustle. I was going to do something different.

And then, by circumstance, I was talking to my friend Daniel Breaker, who I did “Passing Strange” with, and he said, “My manager’s been wanting to meet with you for years.” I was, like, “No, I’m not interested in meeting with anyone. I just let go of my manager, and soon I’m going to let go of my agent.” He said, “I just think you should meet with them. They’re good guys.” I had a meeting with them, which was a terrible meeting, because I sat there with my arms folded. I said, “Listen, let me just make things clear. This is what my skill set is. I just don’t think that I have access or agency in this industry.” They said, “Great, we would love to work with you.” I said, “How about we work together for six months and see what we can build?” They agreed, and things started changing immediately.

This is the part that my working-actor friends are going to be very interested in, this magical moment when you turned things around.

Here’s the thing I tell actor friends, and I’ve never said this in print: I really don’t believe that anyone should bang their head against something that’s not really possible. I would never tell someone, “Just keep going. You got to have that dream.” No, you have to do things that make sense, too. I don’t want you to be homeless and still fighting for your dream. You might need to move to a different city. Your dream may need to happen somewhere else. [He chews on the chocolate bar.] This chocolate is so good! Oh, my God, Michael!

Now I’m really regretting not being in the same room for this interview.

It’s fizzy in my mouth. It’s like a soda and chocolate. It’s amazing. If I find more of it, I’ll send it to you. I would tell any fellow-actor, Just do what makes sense. For me, it didn’t make sense being in my mid-forties and not having any sort of net anymore. I thought my life as an artist may be coming toward an end. I’ve never been a person who put my career in front of having a life. I always wanted love and friendships and travel and good food. [Considers the chocolate.] This is really weird, really popping and snapping in my mouth. I’ve gone from being delighted by the chocolate to being slightly concerned about why there’s a Rice Krispie crackle in the back of my mouth.

That sounds, honestly, incredible.

[He looks at the wrapper.] Oh, A24 made it. It’s a gift from A24, so it won’t kill me. Unless, Michael, this is the last conversation I have, and then I just pass out.

And you’ve got an A24 hat, too! They’re really taking care of you. So, was “Fear the Walking Dead” the project that turned things around?

Yes. I got cast on the same day for Baz Luhrmann’s “The Get Down” and “Fear the Walking Dead,” and both of them were from self-tapes. But it was because my tapes were actually being seen. From this boutique agency that I was with for years, a lot of my work just wasn’t being seen. I had no access. And then I booked both of those jobs, and I had to make a choice. It was a show that shot in New York with Baz Luhrmann, and then there was the possibility of doing this genre show, and I didn’t know anything about “The Walking Dead.” I thought, I want to do something new that I’m uncertain of. And I’m glad I did, because that lasted eight seasons and gave me new footing on this path.

Is there any part of you that wishes that this had all happened in your twenties or thirties, instead of in your forties and fifties?

Absolutely not! None of it! My whole path has been pretty divine. All the missteps and the things I didn’t have access to—I wouldn’t be able to do what I’m doing now if I didn’t have all that, if I didn’t have all these down times and low times and rewiring-how-I-work times. I’m very happy that at fifty-five years old I’m where I am. I would not have wanted this at twenty-five. I probably thought I wanted it, but it wouldn’t have been good for me. I know how to handle this now. I know how to be affected or not to be affected by what people say, what people write. Everyone can have their opinion. That’s what they’re paid for. But I know what’s true for me. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com