Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

In the annals of American time, the November 22nd that happened sixty years ago today still casts a very long shadow. It is a cliché, but true nonetheless, that certain events are singularly imprinted—or, maybe, emblazoned—on the consciousness of entire generations. That November day remains pivotal for my generation, as Pearl Harbor was for my father’s, or 9/11 for my daughter’s.

What is perhaps less evident is how these events not only forge a strong memory, but will suddenly make memory exist, turning our minds inside out. Whereas private things rising from within ourselves had once reigned, public things, coming from outside, now take pride of place. The private obsessions come back, of course, but the public ones now become hard to shake or ignore. My father feels this way about Pearl Harbor, which happened when he was six. Before the attack, he had been a kid on whom outside events, baseball aside, impinged remotely and vaguely; after, he became a hungry newspaper reader—until a few years ago, I had his collection of Philadelphia Bulletin front pages, documenting the war—and, in the most basic sense, he became a man of the world.

November 22, 1963, which occurred, neat near-symmetry, when I was seven, had the same effect on me. I was walking home from school and heard the news from a stranger with a transistor radio and saw my father, very uncharacteristically—he was not even much of a Kennedy fan—in tears in our front yard. (He was hardly alone. Robert Lowell, the poet and passionate conscientious objector, wrote that he was “weeping through the first afternoon.”) My inner obsession at the time, I will confess, was the animated version of “Casper the Friendly Ghost”—I had the first serious crush of my life on his friend, Wendy the Good Little Witch—and I knew instantly, with the sickened, oppressed prescience of children, that Saturday-morning cartoons would be cancelled. Yet if before that day I was only vaguely aware of World Events—I can recall my parent’s anxiety at the Cuban missile crisis, a cloud of ominous apprehension a year before; and can see Dr. King on black-and-white television delivering his “I have a dream” speech against a background of preoccupied observers—I still had the interiority, what we wrongly call the innocence, of childhood. From then on, everything that happened out there happened in me. I can recall every public moment, from the escalation in Vietnam that Kennedy’s successor began to the subsequent assassinations and of course all else since—it’s as crystal clear as, well, a Saturday-morning cartoon. And, like many, I later shared the obsession with the details and imagery of the assassination, so that the single-bullet theory, the overpass, the triple underpass, the Moorman polaroid, the sixth floor of the Book Depository, were all eerily familiar to me, with all their ominous and dreadful associations.

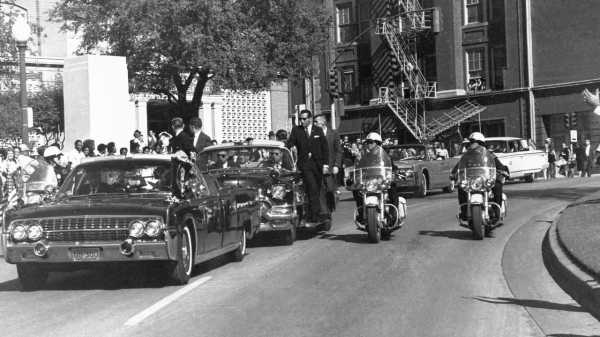

And so, it was with a sense of personal obligation this past spring—in Dallas on a book tour, and impelled by an invigorating cocktail of curiosity and that 9/11 daughter’s order to walk ten thousand steps a day—that I finally walked down to Dealey Plaza, which I had seen so often in so many photographs of those sad and horrible seconds. I was at first shocked—but shocked by the predictable shock that we encounter whenever we visit a famous place about which we have often read: how much smaller it is in reality than our imagination had rendered it. A truth equally applicable to the bedroom where Lincoln died and of Omaha Beach in Normandy. They are more diminutive in scale than the intensity of our searching had made them.

I was still more startled—I am sure I shouldn’t have been, but I was—by the truth that nothing significant had altered in the layout or the articulation of Elm Street in the nearly sixty years since: the triple underpass is just as it was, and hundreds of speeding cars ran right through it as I stood there. Millions of cars, during these six decades, must have passed over exactly the same asphalt that J.F.K. experienced in his last conscious seconds on Earth, with the spot where the fatal shot struck marked merely by an “X” in the roadway. Not the same cars, and not the same asphalt, obviously, but the same pattern of traffic. It is as if Ford’s Theatre were still in place not as a museum but as a living theatre, never altered, with the President’s box still regularly occupied by theatregoers who have only a vague sense that something important once happened there.

I will also confess, to the ire of those conspiracy theorists for whom Dealey Plaza remains an obsession, that, for me, the sheer smallness of the place confirmed the likelihood that the familiar account of the assassination, or the “cover story,” if you insist, is true. The distance between the sixth floor of the Texas Book Depository and that fatal “X” is, for a rifleman, minuscule. It would have been hard for anyone to miss. And it would have been wildly impractical to plan an ambush at the location—no way for anyone to have been concealed behind the picket fence, refurbished but still there, or within the stone pergola, still there. If there were hidden assassins on the grassy knoll, a crowd of people could not possibly have failed to see them.

I am, I should add, a conspiracy skeptic, and inclined to think that the conclusion that the American security and intelligence services arrived at shortly after the assassination, that it had been done alone by a disgruntled marine named Lee Oswald—with the Harvey interjected into his name that afternoon and never quite leaving it, three names somehow becoming what assassins demand—seems the most plausible of all. The reasons for this, as skeptical encyclopedists from Gerald Posner to Vincent Bugliosi have documented, persuasively if not successfully, are simply that a mountain of evidence of all kinds points to Oswald’s sole guilt: firearm-identification evidence and eyewitness evidence and earwitness evidence and autopsy evidence. There is evidence ranging from the testimony of the friend who drove Oswald to work with a packet of “curtain rods” that clearly held a rifle to the certainty that Oswald had tried not long before to assassinate another political figure, the right-wing general Edwin Walker. The odds that all of this mountain could have been deliberately fabricated and held in place without its falseness coming obviously (as opposed to occultly) apart for sixty years seems unlikely. But no amount of this evidence can alter the conviction that a conspiracy was at work for those inclined to believe it, a conviction reinforced by the companion truth that those security services—the F.B.I. and the C.I.A., particularly—really were up to their armpits in conspiracies of their own, hidden from view then but all too obvious now. That these agencies were not responsible for this plot, but thought that some other participant might have been, seems true, too.

Photograph by Laurent Grandguillot / REA / Redux

More important on this occasion, I had always assumed that “Dealey Plaza” was what you saw in the photographs and films of the assassination—the bits of architecture you see in the Zapruder film, with the strange Deco arcade to the right and the two sloping “knolls” to either side. A puzzling thing, really, for this place to have such an elaborate name, as it looks just like a traffic turn, hardly worthy of a name at all. During my visit, I realized that the part one sees in all the photos is just the weaker, right-hand extension of Dealey Plaza—which is actually a quite grand W.P.A.-Rockefeller Center-style monument that encloses the green space opposite the entire triple underpass and has its imposing face right up on Houston Street, where Kennedy drove seconds before the turn onto Elm. It’s really quite well done, one of those Cubist-derived geometric grids, white with punch-holes within, typical of the period. The plaza is finished by a grand, proud, dignified statue of Mr. Dealey himself, the Civic Benefactor, who gave the place its name—the last statue J.F.K. ever saw as he looked to his left—and to whom the plaza was dedicated as a sign of Dallas’s coming of age as a town of speeding traffic, not loping cows.

Standing there on Elm and Houston, where I had been so many times before in my imaginings, I thought of how W. H. Auden, in one of the rightly best-remembered poems of the twentieth century, his “Musée des Beaux Arts”—the one about Bruegel’s painting “Landscape with the Fall of Icarus”—pointed out that horrible things take place “while someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along.” His point is that the things we recall forever—the fall of Icarus, the Archduke’s assassination—are actually tiny blips of action and explosion that occupy mere seconds of existential time, even while occupying endless presence in historical time.

It was surely what Walt Whitman was after, too, when, in the wake of that earlier assassination in 1865, he wrote the most profound and peculiar of American elegies, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” A poem that embraced the violent death of a President as, in the end, a positive and even sacred thing, emphasizing not only loss but the renewal that would take place—not through the cycle of nature alone but also through the collective action of the nation enduring and persisting: “the city at hand with dwellings so dense, and stacks of chimneys, / And all the scenes of life and the workshops, and the workmen homeward returning.”

The event that changed the world was a small part even of its own world. Historic time is the time line of those inside-out turning events. Human time is the time of trudging from hotels and driving through Dealey Plaza without being quite aware of where you are. I had been turned inside out by what happened on the plaza and, looking at it, was turned back inside. Revisiting a historic space, we take historic time and put it back in human time; a spot fetishized by violence becomes only one small incident in a larger and unchanging and almost comically complacent architecture. We disenthrall ourselves from obsession by seeing things as they are, in all their cosmic inconsequence. We can only cure, or at least emancipate ourselves, from trauma with time. That life goes on, and cars still roll by, and people trudge past places which, though history has happened in them, are still places where human time reigns—this is a truth rendered only more urgent by its obviousness. Dealey Plaza is a moment in history, and it is just an ordinary place in an ordinary city. It was a good walk to take. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com