Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Let’s start with the photographer himself. A self-portrait, which, like the rest of Han Youngsoo’s work, is in black-and-white—not a nostalgic choice, just the technology of the times. It’s deep winter, 1958, and he’s standing outside, on the frozen Han River, the massive waterway that bisects Seoul, which he once likened to “a mother’s breast.” A gentle snow falls. Behind him are two bridges, foreshortened at a tilt, and an ice fisherman, shivering in a Siberian-style hat. No such quiet, wide-open space can be found in contemporary Seoul. Han, looking almost cartoonishly mid-century metropolitan, wears a dark coat, with the lapel snapped up, over a white shirt and a dark tie. His jet-black hair is cleanly parted and oiled; his face, big and round. He holds a small Leica rangefinder with a 50-mm. lens to his chest.

This period, a decade after the end of the Korean War, is often depicted—by my parents’ generation, who were children at the time, and later in books, film, and TV—as one of hunger and hardship, of basic survival. It’s easy to forget that, even during war and reconstruction, artists keep making art. And that postwar life is about more than staying sheltered and fed. Han’s photographs reflect a sharp, inexorable striving—not only for safety but also for romance, learning, exploration, and aesthetic pleasure. There are more pictures like the self-portrait: stylish couples on dates, businessmen in taxis, a beauty-pageant contestant onstage.

Sogong-dong, Seoul, undated (1956-1963).

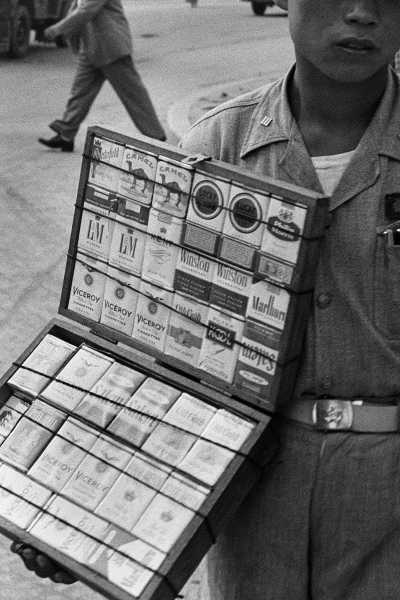

Han shot in many areas of Korea, but Seoul was his home base and muse. The residents of his pictures speed walk and gossip, drink coffee, sell newspapers and dried fish, repair shoes, ogle at posters and mannequins (ready-made clothing was just becoming a thing), sunbathe, hang noodles out to dry. Signs contain words spelled in Hangul (the Korean script) and Chinese characters. As time goes on, more and more English gets mixed in. Traditional architecture, clothing, hair styles, and shoes give way to a global American uni-style.

Myeongdong, Seoul, undated (1956-1963).

Bigak Pavilion, Sejongno, Seoul, 1957.

Han was born in 1933 and grew up in a wealthy family. He studied painting and took photographs for fun; he was protected, but not wholly insulated, from the harsh conditions that resulted from Japanese rule, the Second World War, and the subsequent U.S. occupation. He fought for the South in the Korean War. “By the time he was discharged from the army, he had enough of butchery and senseless death,” the Hungarian curator Kincses Károly has observed. For the rest of the nineteen-fifties and sixties, he committed himself to “minute, insignificant traces” of life. He shot steadily, in a mode similar to that of Henri Cartier-Bresson (the elevated ordinary of Paris) and Helen Levitt (stoops and sidewalks in New York). As part of the social realist Shinsunhwae (신선회), or New Line Group—which also included Lee Hae-moon, an artist, Kim Han-yong, a commercial photographer, and the photojournalists Ahn Jong-chil and Jung Beom-tae—Han sought to create an archive of working-class society that was unembellished, yet respectful and humanistic.

Hapdong, Seoul, 1957.

Namdaemun Market, Seoul, 1957.

During Han’s lifetime—he died in 1999—he was primarily known for his commercial work. In 1966, he founded Han’s Photo, one of the first studios to specialize in advertising (cosmetics, electronics) as South Korea’s consumer age was ushered in. He occasionally showed his artsier street photography, and published selections in the 1987 book “Korean Lives” (삶). In the introduction to that text, he wrote, “The eye of the camera opened my own eyes to the human situation. . . . We have grown along with the nation in an era of rapid modernization.” After his death, his daughter Han Sunjung devoted herself to his archives, leading a project of sorting through thousands of negatives and prints, trying to make sense of what she describes as “the puzzle of Han’s fragmented memos, stuck at angles on files of film, photo captions and descriptions published in catalogues.” So far, she has published four books of his pictures, organized thematically. Exhibitions have been mounted at museums in Korea, France, Hungary, and the U.S. I saw a selection from the latest book, “When the Spring Wind Blows,” focussed on images of women, at a gallery show last year in Manhattan.

Han practiced a genre I might call abstract vérité. There is always the human form on the one hand, and lines and shapes on the other. According to the artist Emile Rubino, Han generally kept a “consistent physical distance” from his subjects; he worked at enough of a remove to allow things to happen, in contrast to the closeup “dominant documentarian aesthetic of that period.” With distance comes so much scenic detail—and movement. Consider the coiled suspense in what initially appears to be a stock-still portrait. The setting is some kind of curio shop: there’s a glass-fronted cabinet, messily stuffed with random things; the tile flooring is stained and cracked. A woman wearing a traditional two-piece hanbok dress—dark jeogori top; light, flowery chima skirt—and with a Hollywood-style soft bob sits in a metal chair, reading a broadsheet. But she isn’t just sitting. She folds herself so acutely that her face is hardly visible. She pours all her concentration into the newspaper. Her posture of absorption is further intensified by the outward splaying of her feet, wrapped in elf-toed beoseon booties.

Myeongdong, Seoul, undated (1956-1963).

The formal composition at work in that portrait is even more evident in Han’s aerial landscapes, shot from bridges and promontories. In one, five women in white hanbok, carrying bundles of white laundry on their heads, form a tight, diagonal spiral (in response to gusts of wind?) against dark fields of grass and cropland. In another, overlooking a Han River marina, there are three interlocking layers: water (most of the picture), hilly horizon, and, at left, a scalloped edge of rowboats and storage sheds that pulls your eyes downward. A small figure of a man in swimming briefs, seen from behind, stretches his arms into a “T.” He is just about to dive off a rickety river barge, but, for this moment, his white body resembles an ornamental cross.

Nodeulseom, Seoul, undated (1956-1963).

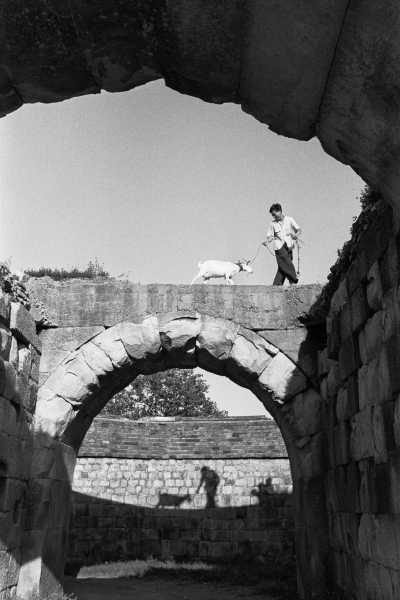

Hwaseong Fortress, Suwon, undated (1956-1963).

Han River, Seoul, undated (1956-1963).

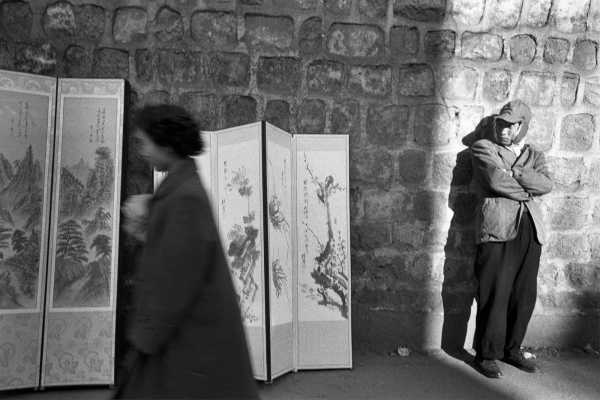

Where such layers weren’t naturally on offer, Han created them by shooting through found surfaces or frames. There’s something of an argument being made: that life after war, in a fast-modernizing and therefore fast-disappearing place, is palimpsestic. I love an image taken in the Mapo port neighborhood of Seoul in 1958. A semi-transparent cloth hangs from a wooden rod in the foreground. Through this gauzy rectangle, we see a woman with a basin on her head (full of rice cakes?) walking with a young girl (perhaps her daughter?) through the tents of an outdoor market—a medley of triangles. Behind them rises a scrabbly slope. Han used holes, windows, and cutouts in a similar way. One photograph, from the Myeongdong shopping district, is nearly all wall, a plane of battered brick and concrete. But a square hole at bottom right reveals a middle-aged couple in the distance, dressed in dark business suits. The man’s face is obscured by his fedora, but he gestures with his left hand; he is explaining something to the woman as they walk toward the edge of the frame.

Anmok, Gangwon Province, 1957.

Gwangju, Gyeonggi Province, 1957.

Suburban Seoul, 1958.

Han River, Seoul, 1958.

“Once Upon a Time,” the second of Han Sunjung’s compilations of her father’s work, features many images of children. Some weeks ago, while flipping through it, I realized that the kids who were climbing inside segments of concrete pipe or reading comic books or fetching well water had been babies during the Korean War and were thus precisely my parents’ age. Was this why I found Han’s photographs so compelling? A stereotype of immigrant households is that they are frozen in time: their vocabulary, foodways, values, and habits pegged to when they left the old world. But here, in these pictures, was the story before that freezing. Han gives us a record of postwar reconstruction, at once earnest and fanciful. His pictures tell us what it felt like to survive, and move on from, obliteration. They are portraits of chaos and dreams.

Yongdo, Busan, 1958.

Myeongdong, Seoul, 1958.

Outside Midopa Department Store, Seoul, 1960.

Near Chosun Hotel, Seoul, 1957.

Sourse: newyorker.com