Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

A little more than a decade ago, the video-game designer Davey Wreden experienced a crippling success. In October, 2013, he and a collaborator, William Pugh, released the Stanley Parable HD, a polished and expanded version of a prototype that Wreden had developed in college, and which he had made available, free of charge, two years before. Wreden and Pugh hoped that they might sell fifty thousand or so copies of the new version in the course of its lifetime. They sold that many on the first day. Wreden was twenty-five years old, and he had everything he’d ever wanted: money, success, recognition. He became severely depressed.

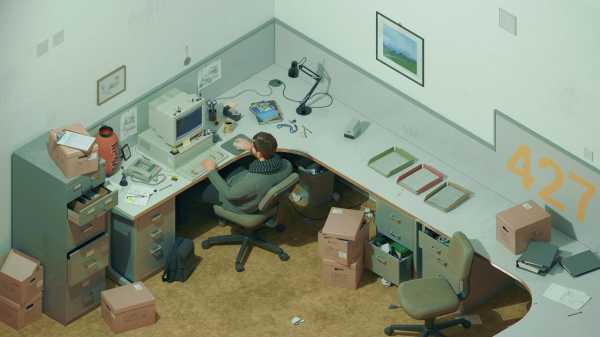

The Stanley Parable is a game about a lonely man. It centers on an office worker, Stanley, who, one day, looks up from his cubicle and discovers that his colleagues have vanished. All that’s left to keep him company is a voice in his head—provided by the British actor Kevan Brighting—which narrates Stanley’s actions. But Stanley doesn’t have to do what the voice says. The game quickly becomes a contest of will between the player and the narrator.

When I first played the Stanley Parable, I was gobsmacked by one sequence in particular, which begins when Stanley walks down a dark corridor marked “ESCAPE.” He finds himself whisked toward a hydraulic press—and certain death, if the narrator’s taunts are to be believed. Just before impact, a previously unheard female narrator (voiced by Lesley Staples) describes how the machine kills Stanley, “crushing every bone in his body.” But the machine doesn’t mush him. Instead, he arrives at a brightly lit museum. Therein lies a small-scale model of his office, with signs explaining how each section was fussed over to insure that the player progresses at a good clip. On the far wall are the game’s credits. The new narrator notes that soon it will be re-started, and Stanley will be alive as ever. “When every path you can walk has been created for you long in advance, death becomes meaningless, making life the same,” she says. Then she adds, “Do you see now that Stanley was already dead from the moment he hit Start?”

I had been playing video games for thirty years, and I had never seen the medium deconstructed so skillfully or with such existential humor. I felt the way that I imagine cinephiles did in 1960, emerging from dark theatres having just seen “Breathless.” The game’s young creators seemed to be free from the trappings of what had come before.

Wreden has since released a second critically acclaimed title, the Beginner’s Guide, and cemented his reputation as a designer who defies convention. Neither of his games asks much more of the player than an ability to move through a 3-D space; what distinguishes them is their philosophical bent and penchant for narrative tricks. (Gabriel Winslow-Yost, writing in The New York Review of Books, invoked Nabokov, calling the Beginner’s Guide “a kind of interactive ‘Pale Fire.’ ”) Among gamers, Wreden has acquired cult-celebrity status, and his influence extends beyond his own medium: even the creator of the TV show “Severance”—another office drama that raises questions about free will as it veers between whimsy and dread—has cited the Stanley Parable as an inspiration. (The game also had a brief cameo in an episode of “House of Cards.”)

Wreden, now thirty-six, has a slim build and a sweep of brown hair. When we spoke for the first time, last year, he was dressed in a dark-gray T-shirt. He works from home, in Vancouver, and the wall behind his desk is adorned with drawings of characters from the video-game franchise Persona, images from the manga Chainsaw Man, and pictures of food. In a corner of the room, next to a bookcase, hangs a ramen-shop paper lantern that he acquired on a trip to Osaka. He was winding down production on his third game, Wanderstop, out this month, and in a reflective mood about its predecessors—works he described as having been designed “to break and unwind the tightly coiled, traditional structure of what games like that were supposed to do.”

As a teen-ager, Wreden loved stories that set traps: “Fight Club” and “The Usual Suspects,” with their late reveals, and works by Roald Dahl and Shirley Jackson. Growing up in Sacramento, California, as the eldest son of a pair of doctors, he gravitated toward brainy but silly humor; he was a big fan of “Weird Al” Yankovic, Flight of the Conchords, and Joseph Heller’s “Catch-22.” Wreden was not an especially happy kid, but from an early age he believed that he could imagine his way to something better. His father once told him that it was hard to have a conversation with him in his adolescence, because Wreden usually forgot what other people said. “It wasn’t, like, a memory thing, or an A.D.H.D. thing,” Wreden recalled. “It was literally just, like, anything that didn’t fit into my big grand plan of doing as much as possible, achieving as much as possible, and thinking as big as possible just wasn’t relevant to me.”

“I’ve had phases of my life where I became not very functional as a person because I couldn’t distinguish myself from the absurdism of the media that I liked,” he said. He responded by creating, in the Stanley Parable, a realm where he could safely explore his own anxieties. “It can’t hurt me because I own it,” he explained. “I thought that if I made a game that spits in the face of an attempt to find meaning in the world, that it would somehow map onto me, as a real person, and I would get over my fear of meaninglessness in the world. And it did not work.”

Wreden has since become ambivalent about the Stanley Parable, feeling, he said, “like a guy who had gotten rich making jokes about video games, trying to deceive real writers into thinking that I’m a real writer.” There was also the shadow of the period after its release, when he became, as he put it, “addicted to praise.” He responded to every piece of fan mail—and hate mail—he received, convinced that any endorsement, rejection, or misapprehension of the game was really about him as a person. Mood swings and sudden bouts of rage alienated his best friend (and then roommate), Robin Arnott, the sound designer for the Stanley Parable, who finally confronted him and said that he couldn’t be around Wreden in this state any longer. Wreden went to therapy; gradually, his depression lifted. The Beginner’s Guide includes a line first spoken by Arnott during the argument that snapped Wreden out of his funk: “When I’m around you, I feel physically ill.”

The Beginner’s Guide was partly inspired by William Goldman’s novel “The Princess Bride,” which Wreden had read while working on the Stanley Parable. Just as the book’s narrator purports to offer an abridgment of a story he’d loved as a child (albeit with plenty of his own editorializing), Wreden thought he might design a documentary-style work around an imaginary game; he was confident no one had done that before. But it was also something far more personal: a game infused with his newfound awareness of the fraught relationship between artist and audience that, as he put it, came from “the deepest place that I could go to within myself.”

In the opening minutes, Wreden—himself a central character—tells the player that he wants to share the work of his friend Coda, an experimental game designer who got his start by tinkering with the same suite of shareware tools that the real-life Wreden had used to create the Stanley Parable. As the Beginner’s Guide progresses, we watch his output grow conceptually richer and more surreal. One of Coda’s games features an outdoor staircase attached to a windowless skyscraper that leads to an inviting wood-panelled room where ideas for new projects float in the air in the form of short sentences. Another level hems the player in with blocks of self-questioning text while the sound of someone gasping for air drones on in the background.

Throughout the game, Wreden offers interpretations of these designs—and also makes small, player-friendly adjustments to the more challenging ones, which he speculates were shaped by Coda’s social isolation and creative frustration. Eventually, it becomes clear that Coda resents these attempts to both alter and evangelize for his œuvre. He upbraids Wreden for seeing in his games a cry for help, and asks the other designer never to contact him again. Wreden confesses that showing Coda’s work to people gave meaning to his life and helped him feel less alone.

From the start of development on the Stanley Parable, in the summer of 2009, until the release of the Beginner’s Guide, in October, 2015, Wreden essentially worked without taking a break. “That was what it took to make those games,” he said. “Somehow I kept thinking that, like, one day this will make sense to me, and I’ll just be able to live like a normal person.” The Beginner’s Guide, like the Stanley Parable before it, won a bevy of awards; Wreden’s reputation continued to grow. But his search for new forms never yielded a sense of personal uplift or fulfillment. It took him years, he said, to see that he had built a kind of mental prison. After the release of the Beginner’s Guide, in 2015, he found that he could no longer write at all.

In January, 2016, Wreden began drawing for upward of five hours nearly every day. He harnessed his obsessive tendencies, producing hundreds of pictures in the course of a six-month span, all of them variations on a simple scene: a pastoral clearing with a quaint-looking tea shop surrounded by trees, rocks, and brooks. He’d deliberately immersed himself in a kind of controlled chaos during the making of the Stanley Parable; this time, he was cultivating serenity. “I really hoped that by working on something that was themed as a relaxing, calming place, that I would relax and calm myself,” he told me.

After founding a new studio, Ivy Road, he realized that the sketches contained the seeds of his next project. Wanderstop belongs to the tradition of so-called cozy games, a burgeoning genre of nonviolent titles devoted to relationships, crafting, exploration, and routine—to building, rather than destroying. (Animal Crossing, a popular franchise that invites players to participate in the day-to-day life of a village, was a particular inspiration; Wreden wanted his game to have a similar vibe, but also “to make space for more complex emotional exploration.”) His approach to its development was, in part, a product of his aversion to writing. At first, he thought that it would be something akin to a toybox, which immersed players in a mysterious and beautiful world without explicit goals or conclusive endings. He wanted to use procedural generation—a technique that employs algorithms to create shifting paths through a game—so that modular chunks of story could be combined in different ways depending on players’ actions. His protagonist, Alta, was silent: a conceit that he described as “my way of procedurally insuring it would be impossible for me to get lost in writing a bunch of dialogue for her.”

Relying on generative systems to do the narrative heavy lifting proved to be a tall order. Wreden playtests his games extensively, and he’ll make changes based in part on players’ reactions. He wanted Wanderstop to have a strong sense of purpose: “It wasn’t just there for you to poke at for a minute, but it actually was trying to speak—trying to effect a sort of psychological therapy on the player, to grant them the permission to relax and to unwind.” But when he shared an early version, he recalled, “The responses could charitably be called ‘muted.’ ” Another writer said that the prototype gave the impression that Wreden didn’t want to be working on the game at all.

Then Pugh, his old collaborator, contacted him about making a version of the Stanley Parable that could be played on consoles such as the Nintendo Switch and PlayStation. Wreden initially planned to add an extra scenario or two, but soon produced what amounted to a full sequel. He’d slipped easily back into the narrator’s voice, because it was essentially his own. When he returned to Wanderstop, he realized that he had to endow it with more of himself, too.

Karla Zimonja played a pivotal role in this reversal. She, too, is a Vancouver-based game developer who made her name with exploration-driven, introspective titles—most notably Gone Home, the low-key story of a young woman who arrives at her family home after a year away and has to piece together what’s happened in her absence. Zimonja told me that she’s known Wreden for more than a decade, noting, “There aren’t too many truly narrative-forward, high-production-values indie people out there.” She joined Ivy Road about a year and a half into Wanderstop’s development, and became Wreden’s editor, pushing him toward what he called “true specifics.”

With Zimonja’s input, the game began to ground itself in a story about Alta, a fighter who’s forced to lay down her weapons and reluctantly ends up managing a tea shop. “I decided to make Alta everything about me that I thought needed healing,” Wreden told me. “She was needy and obsessed with perfection and totally unaware of how much she was hurting herself.” After he drafted the character’s backstory on a whiteboard, a colleague pointed to it and said, “This is the first time I’ve actually felt invested in this game.”

Wanderstop is the most conventional game that Wreden has made. For that reason, it’s also the most difficult project he’s worked on. Both the Stanley Parable and the Beginner’s Guide were relatively simple to build; Wreden spent the bulk of his time writing and tweaking the narration, so that a fairly basic set of actions would feel “like something grand and captivating.” Wanderstop, by contrast, has mechanics—for gardening, resource-gathering, performing little tasks for other characters—that require far more technical know-how to implement.

At first, when I tried Wanderstop myself, I was caught off guard by its unironic embrace of familiar video-game activities: in order to provide Alta with what she needs to operate the two-story infuser that dominates the inside of the shop, I collected ingredients and cultivated plants whose fruit could be used to endow a given brew with a distinctive flavor, or even with mind-stimulating properties. Once I got over my surprise, it didn’t take long to fall into the enjoyable routine of making tea for people and listening to what they had to say.

But Wreden has Trojan-horsed a trauma plot into this seemingly soothing environment. With Wanderstop, he twists the cozy formula, just as his previous works have played with other game-design tropes, telling what he’s described as “a really unpleasant and uncomfortable story in a format designed around comfort.” Alta has a dark alter ego—the personification of the goading internal force that won’t let the former fighter rest—and risks encountering this side of herself whenever she strays too far from the tea shop. The possibility that Alta might ultimately revert to her old ways mirrors Wreden’s anxieties about reverting to his own. “I think if I were to imply that going through this set of events permanently fixed her, it would be radically disingenuous to the actual nature of growth.” All too often, Wreden added, “Your body, for whatever reason, just jettisons the lessons out the air lock, and then you have to relearn them over again.”

In a lecture at Aalto University, in Helsinki, in 2015, Wreden declared that a “fearful state of mind” within the mainstream video-game industry had led to “an art form in which by far the most ubiquitous form of expression is that of firing a gun.” We have, he went on, “a culture where violence is understood and implied to be the central means of problem-solving.” Wanderstop is a kind of rebuttal, prizing dialogue and contemplation over heroic acts. Though Alta spends most of the game longing to fix herself—i.e., to become a fighter again—she must confront the possibility that there may not be a satisfying solution to her problem. In this way, Wanderstop explores a situation which, as Wreden noted in his lecture, often falls outside the purview of video games: namely, how one lives with the consequence of not getting what one wants.

When I asked Wreden about those remarks, he said that he regrets some of the more hard-nosed things he’s said in the past—then allowed that maybe he’d grown soft, complacent. He likes that some creators push boundaries, he said, while others entertain. “I just want FromSoftware to keep making Sekiro,” he told me, name-checking a Japanese video-game company and its popular samurai game.

Near the close of our last chat, I asked Wreden where he thinks he’ll go next. He noted that, up until now, the arc of his career has been to move from the absurd to the practical. His desire for Wanderstop to have genuine therapeutic potential is a reflection of that shift. “A pet peeve of mine has really become when people say, ‘I just wanna ask questions,’ ” he added. This, he said, was something you hear “from a lot of big and popular creators”; it was also an impulse that you could find in his work. “It is something that I have plumbed the depths of, and I have come up and found it wanting,” he said. “Questions aren’t good enough for me anymore. I would like to start talking about answers.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com