Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

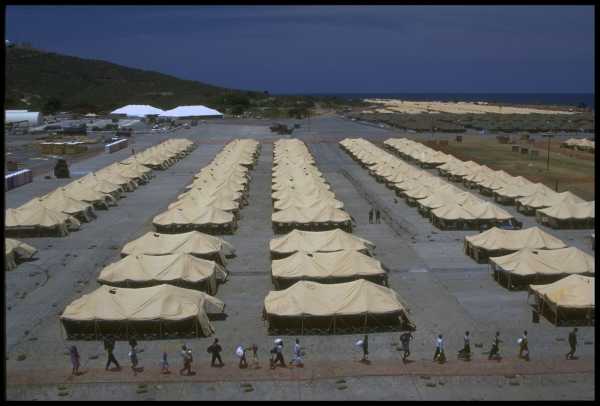

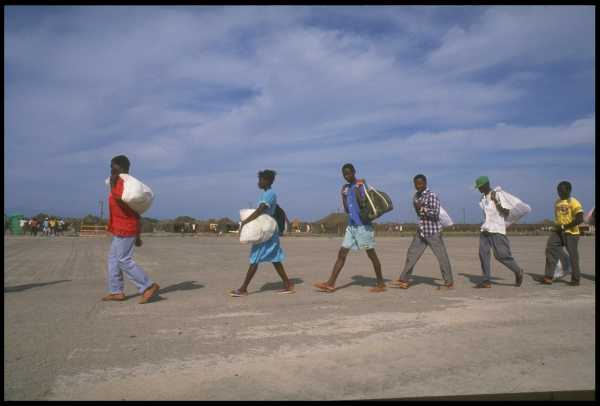

Ninaj Raoul has certain images seared in her mind from her trips to the United States’ Guantánamo Bay Naval Base. Raoul, the co-founder and executive director of Haitian Women for Haitian Refugees, a Brooklyn-based immigrant-advocacy group, served as an interpreter for Haitian asylum seekers who were imprisoned at Guantánamo in the early nineteen-nineties. During her many visits there, she recalls, the base was always scorching hot. There were no trees nearby, just rows and rows of tan and olive-green tents erected on cement and surrounded by airport hangars, porta-potties, barbed wire, and guard towers. Most of the tents had minimal airflow, and people were packed into them like sardines. Some of the detainees were being held with their children. Others had been separated from them. There was little privacy except what people achieved by hanging sheets between field cots. The camp was infested with mice, the air filled with flies, and the detainees would get soaked, even inside the tents, when it rained. Iguanas roamed inside the perimeter along with rodents known as banana rats that were the size of cats. I asked Raoul to share her memories recently in light of Donald Trump’s directive, on January 29th, ordering the expansion of the Migrant Operations Center in Guantánamo into a thirty-thousand-bed detention center. Scenes similar to the ones she describes were captured by photojournalists who visited the base at that time. Their work, a selection of which appears here, now seems like a preview of what’s to come.

Photograph by William Campbell / Getty

Photograph by William Campbell / Getty

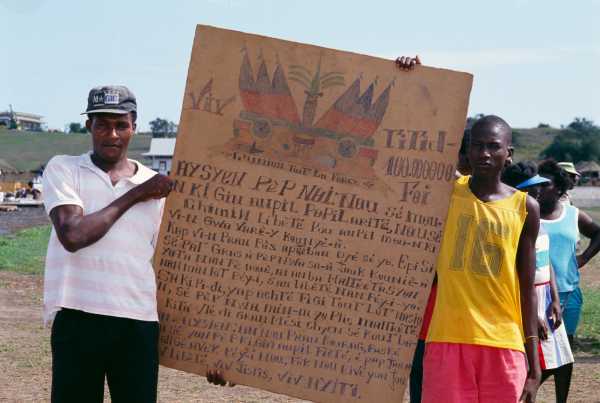

Situated on the southeastern coast of the island of Cuba, Guantánamo was the site where U.S. troops first landed during the Spanish-American War, in 1898. The United States secured access to the base in 1903, through a postwar agreement that pressured the Cubans into leasing out some of their territory in exchange for independence. After a coup d’état in September, 1991, against Haiti’s first democratically elected President, Jean-Bertrand Aristide, tens of thousands fled on packed boats to escape a Haitian military; some of its leaders had been trained in the U.S. Haitians were detained at Guantánamo, along with Cubans who were also seeking asylum in the United States. Whereas the Cubans were considered to be fleeing political persecution, the Haitians were generally labelled as economic migrants, which made them less likely to be granted asylum expeditiously, if at all. To pass the time, detainees stared at the mountains in the distance and played soccer and dominoes. They sang and prayed and waited, sometimes for months.

Photograph by Jeffrey Boan / AP

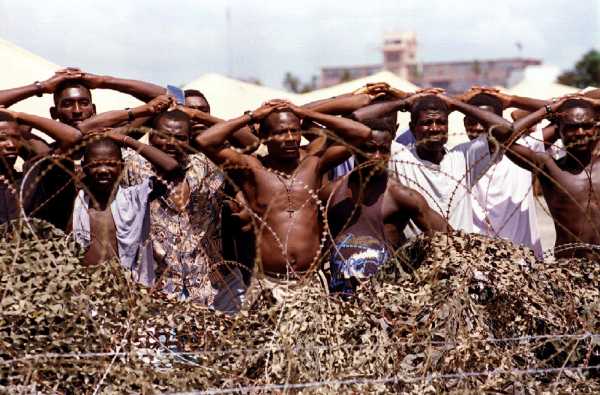

“It was one of the loneliest places on earth,” Carl Juste, a Miami Herald photographer who travelled to Guantánamo twice in the nineteen-nineties, recently told me. “People felt as though they’d been dropped in the middle of nowhere. If not for the sea, you might think you were in the desert somewhere.” Trailed by military escorts, Juste and other photographers were allowed to document only approved scenes, but he and fellow-photojournalists circumvented that, he said, by focussing closely on details of the detainees’ experience: a child grasping a woman’s finger; hands interlaced over crestfallen faces, their expressions signalling tèt chaje—we’re in serious trouble.

Photograph by Steven D. Starr / Getty

Raoul vividly remembers an uncaptured moment in 1993 during a trip with a Yale law clinic led by students and their professors. She saw detainees sitting with hands and feet shackled in the hot sun in the middle of a field. Some of the military guards yelled at the team, and, when she tried to take a picture, one reached out and tried to grab her camera. She managed to capture a blurred image of his hand reaching toward the lens. The detainees, some of whom had qualified for asylum but were barred from entering the U.S. because they were H.I.V.-positive, had been holding up cardboard signs in protest and participating in a hunger strike. Some later told visiting journalists and human-rights observers, including the Reverend Jesse Jackson, that they were being treated like prisoners of war. Many of the detainees were thrown into the brig or underground prisons. Some women endured vaginal searches, and there were also reports of sexual assault. A Navy corpsman was court-martialled on allegations of rape. “It was a lawless place,” Raoul said. “There was no accountability.”

Photograph from IMAGO Images / Reuters

In “Forever Prison,” a segment of the PBS documentary series “Frontline” from 2017, a woman named Marie Genard, who was fourteen when she was detained at Guantánamo, along with her father, said, “We didn’t have no rights because technically we’re not in the U.S. So it felt like you were in prison. I mean, that’s what it was to us.”

Photograph by Chris O’Meara / AP

Ira Kurzban, an immigration lawyer who was among the first to represent detainees on Guantánamo, said, in an oral history filmed for the Guantánamo Public Memory Project, that the base became a kind of gulag. “By saying, We do not want to keep people physically in our country, so let’s find a place where we can keep them out of sight,” he said, adding, “There was a great deal of human tragedy that was hidden from the American people.”

Photograph by Steven D. Starr / Getty

Photograph by Shepard Sherbell / Getty

In 1993, Judge Sterling Johnson, Jr., from the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New York, ordered the release of the Haitians detained in Guantánamo. Nearly a decade later, 9/11 terrorism suspects were jailed at Guantánamo, where they were subjected to “enhanced interrogations techniques” including waterboarding, a torture technique that Trump, when he was campaigning for President in 2016, promised to bring back—along with “a hell of a lot worse.”

Photograph by Steven D. Starr / Getty

Juste recalls global outrage prompted by a photograph from 2002—taken by a U.S. Navy photographer, Petty Officer First Class Shane T. McCoy, and released by the Defense Department—of caged, blindfolded, and shackled men on their knees in orange uniforms in a yard at Guantánamo and, later, the shocking images of prisoner abuse and torture taken by gleeful U.S. military personnel in Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison in 2003.

“If this current Guantánamo project continues,” Juste said, “you have to hope that there will be people in there, perhaps whistle-blowers, who will tell or show what these people are going through—their actual experiences, not just what the government wants us to see.”

Photogaph by Jeff Christensen / Reuters

What the government appears to want to show, through videos and photographs distributed primarily through social media of home and workplace raids and arrests, is debasement and humiliation, casting undocumented immigrants, including women and children, as global villains in a “Cops”-like reality-show atmosphere. Government-friendly news outlets and television personalities such as Phil (Dr. Phil) McGraw help further spread the message by embedding with Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents who have been told to be camera-ready.

On February 4th, ten Venezuelan men, their hands and feet shackled, were brought to Guantánamo from El Paso, Texas, on a military plane. Photographed before their departure, they were described by officials with the Department of Homeland Security as “the worst of the worst” (language which had previously been used to describe 9/11 terrorism suspects), and as members of the Tren de Aragua gang, which the Trump Administration recently designated a terrorist group. One woman who identified her brother in the photographs, which were shared on social media, told the Times that he had only recently moved to the U.S. and was not a gang member. Over the following weeks, a hundred and a sixty-eight more detainees followed; all but one were later flown from Guantánamo to Venezuela. Fifty-one of the men had no criminal records. On February 24th, the Administration reportedly paused its plan to bring more detainees to Guantánamo because the tents that had been erected failed to meet “detention standards.” The plan is also facing several lawsuits backed by the A.C.L.U.

Photograph by Steven D. Starr / Getty

Soon after Trump signed his Guantánamo directive, he ended Temporary Protected Status for more than three hundred thousand Venezuelans and half a million Haitians, making them eligible for deportation in the coming months. The Administration is considering other detention sites in the U.S. and elsewhere, including in El Salvador, where, according to Human Rights Watch, even minors are subject to torture and abuse while incarcerated. In mid-February, a group of detainees including Iranian, Indian, Afghan, and Chinese immigrants were deported from the United States to Panama. They were confined to a hotel for several days. Most agreed to go back to their home countries, but more than a hundred expressed fear of returning and were moved to a preëxisting camp on the edge of the Darién Gap. A group of lawyers recently filed a petition before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights on their behalf and plans to file a complaint against the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. On Friday, Panama announced it would release them, granting temporary passes to remain in the country for between thirty and ninety days.

Unlike the detainees at Guantánamo in the nineteen-nineties, a few today have access to phones and are able to sporadically communicate with reporters and photographers. Some of the men who were deported from Guantánamo to Venezuela have told a familiar tale of being beaten by guards, strip-searched, and put into solitary confinement, and of suicide attempts as well as hunger strikes to protest the inhumane conditions. As for the detainees by the Darién Gap, one Iranian held there, Artemis Ghasemzadeh, told the Times, “It looks like a zoo, there are fenced cages.” Unfortunately, as many of the old photos of Haitians in Guantánamo remind us, that’s exactly the point.

Photograph by William Campbell / Getty

Sourse: newyorker.com