Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Alex Barasch

Culture editor

You’re reading the Goings On newsletter, a guide to what we’re watching, listening to, and doing this week. Sign up to receive it in your in-box.

If your first thought, as we ushered in the New Year, was not of fresh starts and resolutions but of the crises looming in 2024 and beyond, the best antidote, culturally speaking, might be to lean into catastrophe. Metrograph has catered to the pessimists among us by curating a series entitled “The Future Looks Bright from Afar” (through Feb. 4), which promises a suite of sci-fi films marked by “grim prognostications” about mankind’s trajectory. (The options are not limited to the obvious dystopias: the final night of the program features a rare showing of “Alphaville,” Jean-Luc Godard’s 1965 neo-noir take on the threat of a fascist A.I.) This weekend’s offerings include the gorgeously animated cult classic “Ghost in the Shell,” which grapples with questions of sentience and selfhood in a high-tech society; later in the month, they’ll screen “Snowpiercer,” Bong Joon-ho’s wildly entertaining, climate-crisis-inflected thriller.

“Godzilla Minus One.”

Photograph courtesy Toho

As it happens, the great new crowd-pleaser of the moment is also a disaster story, albeit one set firmly in the past. “Godzilla Minus One” follows a kamikaze pilot who shirks his duty in the final days of the Second World War—a decision that puts him in the path of the eponymous monster and, years later, leaves him uniquely motivated to stop its rampage through postwar Tokyo. Elevated by emotional and historical specificity as well as set pieces that belie its modest fifteen-million-dollar budget, Takashi Yamazaki’s contribution to the Godzilla canon is simultaneously a study in survivor’s guilt and a “Jaws”-style blockbuster, complete with the revelation that our protagonists are going to need a bigger boat. The movie, which opened in the U.S. in December, became a word-of-mouth phenomenon whose twists had audiences shouting at the screen; it’s now one of the highest-grossing foreign-language films of all time. A little catharsis, it seems, goes a long way.

Spotlight

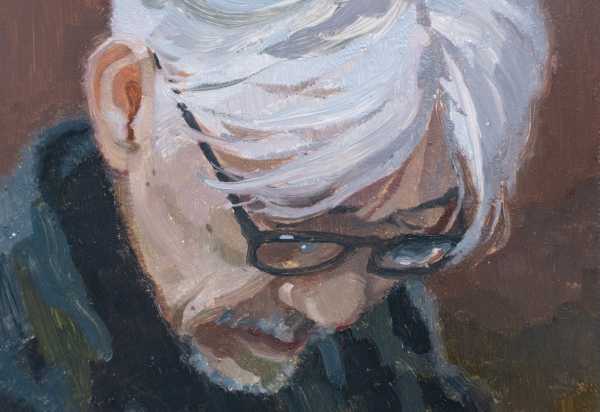

Illustration by James Lee ChiahanMusic

Among the accomplishments of the intrepid pianist and composer Ryuichi Sakamoto—who died in March of last year, at the age of seventy-one—was his work with Yellow Magic Orchestra, in the late seventies and early eighties, which greatly influenced electronic music and hip-hop. His curious solo pursuits spanned pop and ambient, the worldly and the avant-garde; his film scores earned him an Oscar, a BAFTA, and a Grammy. As the 2024 Winter Jazzfest comes to a close, the artist’s life and legacy are commemorated in a concert, at Roulette on Jan. 17, featuring the Sakamoto Tribute Ensemble, DJ Spooky, and the experimental performer Yuka C. Honda, along with special guests, raising funds for the Trees for Sakamoto foundation.—Sheldon Pearce

About Town

Television

History is an oppressive force in “Fellow Travelers,” but, miraculously, Showtime’s eight-part adaptation of Thomas Mallon’s novel seldom gets bogged down in tragedy. Sensual and heartfelt, the show traces the thirty-odd-year relationship between two men (Matt Bomer and Jonathan Bailey) who first meet in the fifties during Joseph McCarthy’s Lavender Scare, when the far-right senator sought to purge not just Communists but gay men and women from government service. Bailey, in particular, lends a winsome unpredictability to the period romance, which is most interested in exploring how these characters respond to the historical circumstances—and, gradually, social progress—that arrive just in time for some, and much too late for others.—Inkoo Kang (Reviewed in our issue of 11/6/23.) (Streaming on Paramount+.)

Classical Music

Kurt Weill’s theatre music is more or less synonymous with Germany’s unstable interwar years, but Carnegie Hall has set itself the task of seeing beyond one composer’s disenchanted, slinkily soulful style in the season-long festival “Fall of the Weimar Republic: Dancing on the Precipice.” Franz Welser-Möst conducts the Cleveland Orchestra, one of the country’s best, in two concerts (Jan. 20-21); of special note are pieces by Ernst Krenek and Anton Webern, whose elusive, atonal music was deemed “degenerate” art by the Nazis. Two days later, the Philadelphia Orchestra, led by Yannick Nézet-Séguin, broadens the impression of Weill as a composer of darkly satirical stage works, with his elegantly airborne Symphony No. 2 (Jan. 23).—Oussama Zahr (Carnegie Hall.)

Dance

Photograph by Quinn B. Wharton

In recent years, many choreographers have been presenting their works as acts of healing. Ronald K. Brown has been doing something similar since he founded his company, Evidence, nearly forty years ago. But, where much of today’s trendy work is self-involved, Brown’s dances bring succor to the audience. The means are musical and kinesthetic, an irresistible blend of African and American modern dance that lifts the spirit. A good example is his 2001 work “Walking Out the Dark,” the centerpiece of his current season. Two couples face off in bodily arguments, get showered in dust, then find reconciliation, as the music traces a path from the American South to Cuba to Africa. It’s diaspora in reverse.—Brian Seibert (Joyce Theatre; Jan. 16-20.)

Soul

The soul duo Black Pumas surfaced out of nowhere when it scored a surprise Grammy nomination for Best New Artist in 2020, and then, a year later, crashed the Record and Album of the Year categories. Its odd-couple members—Eric Burton and Adrian Quesada—have a provincial origin story: seeking a singer, Quesada put out feelers for talent in Austin, turning up the unknown Burton, and they worked out their material weekly at a local bar. Fittingly, their stirring, ageless music sounds juke-joint-tested and stage-ready, tender yet massive. The duo is joined by the reunited nineties jazz-rap outfit Digable Planets, which shares its affinity for dusting off vintage sounds.—Sheldon Pearce (Radio City Music Hall; Jan. 19.)

Movies

Jon Bernthal and Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor in “Origin.”

Photograph by Atsushi Nishijima / Courtesy NEON

In this season of one-word-title bio-pics, Ava DuVernay’s “Origin” stands out for its innovation and audacity. It dramatizes how the journalist Isabel Wilkerson (Aunjanue Ellis-Taylor), motivated both by grief in her private life and by public tragedies (particularly the killing of Trayvon Martin), wrote her acclaimed 2020 book, “Caste.” Wilkerson’s study traces thematic connections between various forms of persecution—including the enslavement of Black people in the U.S., the oppression of Dalit people in India, and the deportation and murder of Jews in Nazi Germany—and DuVernay pays rapt attention to the author’s intellectual labor. Displaying the personal dramas arising in the course of Wilkerson’s international journeys and depicting historical events detailed in her work, DuVernay’s complex blend of fiction and documentary, theory and experience, is deft and thrilling.—Richard Brody (In wide release.)

Off Off Broadway

In show after show, Julia Mounsey and Peter Mills Weiss create simple masterpieces of dread; they murmur seemingly true horror stories, which wriggle into our minds like worms into soil. Their latest, part of the Under the Radar festival, the surprising and heartfelt “Open Mic Night,” however, implants something far more dangerous: grief. As a way of paying tribute to their recently shuttered D.I.Y. performance space, Life World, the deadpan Mills Weiss re-creates a (putative, hilariously terrible) crowd-work standup routine—he offered one theatregoer “a choice between two continuums or a binary”—as Mounsey gives live critique. The audience laughs, but eventually we realize that we’re participating in a wake for a theatre. The two chief mourners barely register us. For them, we become another sound effect, there to approximate, for a moment, the sound of a vanished room.—Helen Shaw (Performance Space New York; through Jan. 18.)

Pick Three

The staff writer Richard Brody shares current obsessions.

1. Francis Ford Coppola, now eighty-four, is everywhere, with the upcoming reëdited rerelease of his 1981 musical, “One from the Heart” (in theatres Jan. 19), and in anticipation of his self-financed science-fiction feature, “Megalopolis,” out sometime this year. There’s also a notable new book, “The Path to Paradise,” by Sam Wasson, that relies on the filmmaker’s archives and hundreds of interviews to form a meticulous portrait of a daring artist who risked his career to establish a studio of his own.

2. The 1953 performance in Toronto of a quintet headed by the saxophonist Charlie Parker and the trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie was released in 1973 as “The Greatest Jazz Concert Ever.” Its new reissue, “Hot House,” is revelatory. The restoration makes the high-flying horn solos stand out all the more clearly and—by exposing the synergy of the rhythm section, the bassist Charles Mingus, the pianist Bud Powell, and the drummer Max Roach—renders the music irresistibly, danceably propulsive.

Photograph courtesy Mubi

3. “Age of Panic,” the first feature by Justine Triet (“Anatomy of a Fall”), from 2013, is a freewheeling blend of fiction and documentary, set on the day of France’s 2012 Presidential runoff. Laetitia (Laetitia Dosch), a TV news reporter and a single mother in the midst of a visitation battle, is sent to cover the rally of the real-life Socialist candidate François Hollande. Triet, who filmed at the actual rally, combines the drama of a working woman’s personal crises with an incisive view of media-driven politics. Now streaming on MUBI, it’s one of the wildest, most original recent French movies.

P.S. Good stuff on the Internet:

- “A Maui Love Story”

- Percival Everett’s American Landscapes

- Ann Patchett on TikTok

Sourse: newyorker.com