Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Where has Charles Bell been all my life? Or, rather, where have his recordings been? Why did I only find out about them now? How have I only now, fifty-plus years after getting into jazz, stumbled upon the existence of a pianist whose albums were recorded in the early nineteen-sixties and whom I instantly considered a major artist—whose work I instantly loved? I first noticed Bell’s name a few weeks ago while idly poking around on the Atlantic Records section of the Jazz Discography Project, a favorite Web site (and a labor of love and heroic devotion), and what piqued my interest about the catalogue entry for Bell’s 1963 album, “Another Dimension,” is that his quartet featured two great musicians whose art and wide-ranging ambition I’ve long admired: the drummer Allen Blairman and the bassist Ron Carter, a key modernist, who’s still busy gigging and recording at the age of eighty-seven. So I went to Spotify, a Bell compilation turned up, and I listened with amazement.

There’s not much information out there about Bell. He was born in Pittsburgh in 1933 and died in 2012. Classically trained (with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in composition from what is now Carnegie Mellon University), he started playing jazz at the age of twenty, fusing his interest in composition with his interest in improvisation. In May, 1960, he led a quartet at Georgetown University’s Intercollegiate Jazz Festival; along with Blairman on drums (who was self-taught and only nineteen), Bell was joined by the guitarist Bill Smith (a Duquesne student) and the bassist Frank Traficante. The group won first prize (Dave Brubeck was one of the judges), which included a record deal with Columbia Records. The resulting album, “The Charles Bell Contemporary Jazz Quartet,” was recorded that July and released in 1961. It was Bell’s only album with Columbia, but, in the next few years, he made two more records, one for Atlantic and one for the obscure label Gateway. He also composed a concerto for jazz ensemble and orchestra, which was performed by the Pittsburgh Symphony, under the great conductor William Steinberg. Bell achieved a modest but definite eminence in the jazz world: when that first album was released, DownBeat magazine awarded it five stars, the highest rating, alongside John Coltrane’s epochal “My Favorite Things.” In 1965, Bell performed at a Pittsburgh festival that also featured Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, Mary Lou Williams, and other luminaries. (Two tracks of his performances there have also been issued.) Also in 1965, Bell moved to New York, became a public-school teacher and a professor, performed occasionally—and then vanished from the jazz scene.

The title of Bell’s first album, “The Charles Bell Contemporary Jazz Quartet,” as the liner notes acknowledge, clearly invites comparison with one of the most popular jazz groups of the time, the Modern Jazz Quartet. The M.J.Q. similarly featured a classically schooled pianist, John Lewis, and was distinguished by an interweaving of jazz and classical styles. But Lewis, though a noteworthy pianist—tasteful and elegant, refined in a classicizing mode, hearty in a bluesy one—was hardly an innovative player. By contrast, Bell’s album is startling from the very beginning, thanks both to his compositions—he composed all seven of the tracks—and to his improvisations. In the first track, “Latin Festival,” only the instrumentation suggests that these contrapuntally intricate and meticulously arranged compositions are anything like jazz. But then the solos start. Smith’s somewhat neutral guitar tone yields a piquantly chromatic, rhythmically intriguing improvisation; three minutes in, Bell comes to the fore, and, hearing him, I was instantly hooked. He plays with percussive energy and a full, rounded tone, unleashing skeins of contrapuntal interplay between right and left hands and even a kind of impulsive chopping reminiscent of the style that Cecil Taylor was then pioneering. I was absorbed by the harmonic audacity of Bell’s sharply etched phrases and by his feeling for space and silences. His bold, pointed placement of notes and chords is exquisite, as in his propulsive solo on “The Last Sermon.” Throughout the album, the recurring harmonies and rhythms of Bell’s compositions don’t at all inhibit his improvisations but, rather, urge them along with provocative, unsettling nudges.

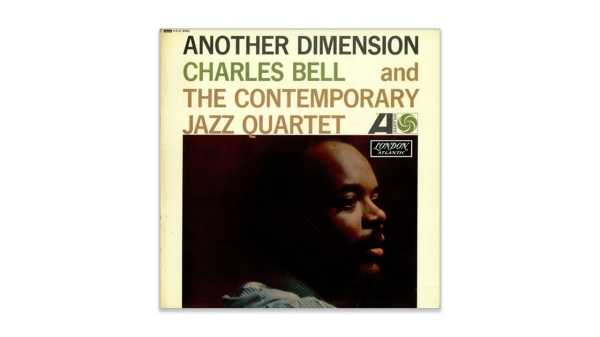

Bell’s next record, “Another Dimension,” was recorded in 1962—it’s the Atlantic album that first caught my discographical eye—and it, too, has seven tracks. Four are by Bell and three are borrowed: Sonny Rollins’s “Oleo,” Lewis’s “Django,” and (daringly, given how recent Coltrane’s version was) “My Favorite Things.” (The album was reviewed hedgingly—by Harvey Pekar—as “interesting listening.”) Atlantic was home to some of the most adventurous jazz of the time, and the quartet (with Carter replacing Traficante) loosens up to match; gone are the first album’s vestiges of M.J.Q.-like reserve. Smith’s guitar tone has more edge, and Blairman is a strikingly melodic drummer throughout, both in his ringing cymbal work and in his gracefully organized tumult as a soloist. As for Bell, his solo on “Theme” bounces and swaggers; on “Bass Line,” he lets loose with some two-fisted thunder; and it’s fascinating to hear his distinctively complex approaches to the three familiar compositions. He infuses the moderate-tempo “Django” with pointillistic swing, and even his comping behind Smith on “My Favorite Things” is grand and gripping.

In his fusion of jazz and classical music, Bell was both faithful to his education and in step with trends of the time, as exemplified by the popularity of the M.J.Q. and of the classical-jazz-fusion movement known as Third Stream. Nonetheless, Bell seems to have been wary of being defined by this fusion. “My music, while using larger forms, will remain—unlike Third Stream—one thing: jazz,” he told the critic Nat Hentoff, in the liner notes for “Another Dimension.” He insisted that “the written sections have only one aim and that is to inspire the improviser,” and it’s clear even from Bell’s recordings of his own compositions that his solos were indeed the focal point of his music.

In his 1963 recording, “The Charles Bell Trio in Concert,” he gave these solos fuller voice. Of the album’s eight tracks, Bell composed only one of them, alongside one by the trio’s bassist, Thomas Sewell; a pair of standards (including “Summertime”); and four modern-jazz classics: Miles Davis’s “Prancing,” Nat Adderley’s “Work Song,” Paul Desmond’s “Take Five,” and “Whisper Not,” by Benny Golson (who’s still around, at ninety-five). Bell has the frontline solo time to himself. His transformations of familiar tunes spotlight the singularity of his ideas, and the concert setting adds energy. Bell’s playing is far more assertive—indeed, his statements of the well-known themes are sometimes as joltingly original as his solos. His improvisation on “Tommy’s Blues” lurches between pealing lament and graceful swing; “Summertime” delivers crystalline dissonances, “Prancing” offers a rollicking stomp of ringing chords and whirling rushes.

Bell’s originality isn’t only in musical form but in the tone he conveys, the voice he conjures. What he borrows above all from European concert music is an elusive formality, less a sense of direct address than of personal exploration. It’s odd but perhaps apt to define his art by what it’s not: not genteel but urbane, vigorous but not vehement, bluesy but with more of the church than of night life. What’s positive in its passionate abstractions is the sense of three-dimensionality, of musical schemas that have the open airiness of modern architecture, the introspective ardor of thought under construction. Listening to his music is an encounter with an extraordinary musical mind—and with a distinctive jazz modernism that was never recognized and never had the chance to exert the influence that it deserved.

In 2000, Frank Rubolino, who’d been a Duquesne student in the late fifties, reminisced about the awakening in Pittsburgh of his passion for jazz, and Bell—engaged as he was with the most advanced jazz of the time—plays a crucial role. Meeting Bell in a record store in 1961, Rubolino bought the quartet’s first album, becoming obsessed with their music and befriending the pianist: “I followed their gigs around Pittsburgh like a rock groupie, catching them every opportunity I could. Bell turned me on to Cecil Taylor . . . Ornette Coleman . . . and Eric Dolphy.” That’s the company that Bell kept, in his musical taste as a listener and a creator alike.

By 1963, Bell was responding to the powerful currents of liberation sweeping through jazz and, as a result, seemingly bifurcating his musical energies—concentrating his classical-based ideas in orchestral composition and focussing his jazz performances on his ideas and identity as a heroic soloist. The two live cuts from 1965, on which Bell is accompanied by the bassist Larry Gales and the drummer Ben Riley—both members of Thelonious Monk’s quartet—reflect a darkly moody fervor roiling its surfaces and feature passages of nerve-fraying rapidity. It’s music of the moment that points even more decisively toward the future.

Meanwhile, Bell took a day job, teaching music in Pittsburgh public schools, but his original methods were considered dubious and he was fired. When he moved to New York and got an elementary-school teaching job there, his original methods proved so successful that, by 1968, he was hired to teach teachers, in a course at Lehman College. “Instead of insisting on exercises and other rigid formulae,” he said in a 1968 interview, “I created little contemporary tunes for each student to practice and learn. If the first one didn’t grab the kid, I’d write another, then still one more, until he found a song that got to him.” He also used this method to teach phonics, and he composed a so-called pop opera, “Big Time Selfish,” which he called “contrapuntal rock ’n’ roll,” for use in school. He added, “Perhaps most important—these young student and professional teachers are bringing music with a black base into our schools, without making a big point of it!”

Bell played, with a quartet, at Carnegie Recital Hall in 1967. In 1969, he gave a performance in Central Park of his “Concerto for Piano, Drums, and Orchestra” with the Harlem Youth Symphony Orchestra and his son, Charles, Jr., (a.k.a. Poogie) on drums. (Poogie, who has had a prolific career as a drummer, was just eight at the time.) In 1972, “The Little Junkie,” a rock opera for children by Bell (then going by the name O’sai Belaka), was performed at Lehman College, in the Bronx. In 1973, Bell reportedly performed his compositions with the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra and the Morgan State Choir. (I hope that his concert-hall music will be published and recorded.) I couldn’t find a trace of any later jazz-centered performance by him; it’s unclear why he let that part of his career go, but, in Robert W. Schachner’s liner notes to “The Charles Bell Trio in Concert,” the writer asked Bell when his previous album had been recorded, and Bell responded, “I have a hard time remembering even last week because everything in front of me is hanging me up.” Whatever measures Bell took to evade what was standing in his way also put him on an altogether different path from the one that led to his brief but brilliant jazz career. His place in history should have been assured; instead, it needs, urgently, to be restored. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com