Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The effort to yoke radical politics to radical aesthetics—to make art that’s revolutionary both in content and form—is as central to modernity as revolution itself is. The Cuban director Sara Gómez, who died in 1974, at the age of thirty-one, is one of the few directors to have truly achieved this synthesis. Before her life was cut short, by asthma, Gómez made about twenty short documentaries, starting in 1961, two years after the Cuban Revolution. In 1974, she shot her only feature-length film, “One Way or Another,” completed posthumously, which mixes a romantic drama with documentary sequences. This feature and fourteen of the shorts are coming to the Criterion Channel on February 1st, bringing to wide attention a body of work that was in the creative and political forefront of its time and, in many ways, remains so even now.

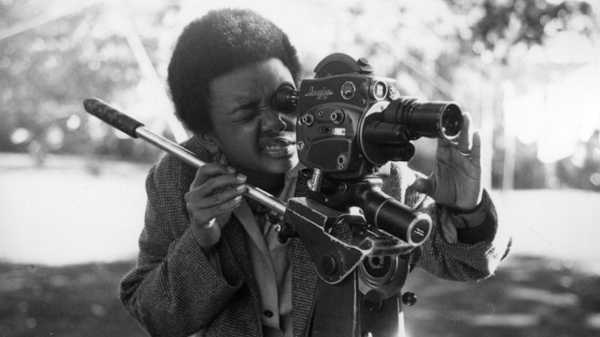

Gómez, born in 1942, into a family of middle-class professionals, was the first female Cuban director—indeed, even now the only Cuban woman to have made a feature—and women’s lives and conflicts are at the center of her films. She was also Black, and her work emphasized the significance of Black culture in Cuba, along with the discrimination that Black Cubans faced. In addition to her identity, her background, and her politics, a kind of cinematic genealogy was crucial to her development of a personalized yet political sense of form: when Agnès Varda visited Cuba in 1962, Gómez worked as her assistant, and the two became friends. Varda photographed Gómez, and a batch of those photos appear in Varda’s 1963 film “Salut les Cubains,” which is also on the Criterion Channel.

Before turning to film, Gómez studied ethnography and music, and the earliest films in Criterion’s collection of her work are regional profiles. “I’ll Go to Santiago,” from 1964, emphasizes the African heritage of the city, Cuba’s second largest, a result of the transport of enslaved Black people from what is now Haiti, in the seventeen-nineties, by French slave owners fleeing the revolution there. In “Guanabacoa: Chronicle of My Family,” from 1966, Gómez returns to her family’s neighborhood, in Havana, and caps off a series of documentary portraits of relatives (and photographic portraits of deceased ones) by interviewing her eighty-year-old great-aunt, who describes her youthful outings in “societies for Black people—for certain Black people.” This allusion to both the segregation of Cuba and the stratification of Black Cuban society elicits a startled response from Gómez and provokes to conclude her film with a challenge, delivered in voice-over: “Will we have to fight the need to be a distinguished, ‘bettered’ Black person?”

In her 1968 documentary “On the Other Island,” Gómez visits the Isle of Pines, which was then home to a Communist Party reëducation camp. The teens and adults who reside there are enrolled in farm labor alongside classes in politics. Gómez downplays the punitive aspect of it, and her subjects self-critically discuss the compulsory manual labor in positive terms. (Like almost all filmic exaltations of physical work, it’s great to watch; when seen for a few seconds at a time, the fatigue, injury, and boredom entailed are invisible.) One of the most extensive interviews is with an opera singer named Rafael. His attitude had been deemed in need of adjustment after he experienced difficulties as the only Black singer in a chorus. He says that he was denied opportunities because of racism and that he even heard explicit expressions of aversion to his appearing onstage with white colleagues. Poignantly, he asks Gómez, “One day, will I be able to star in ‘La Traviata’?”

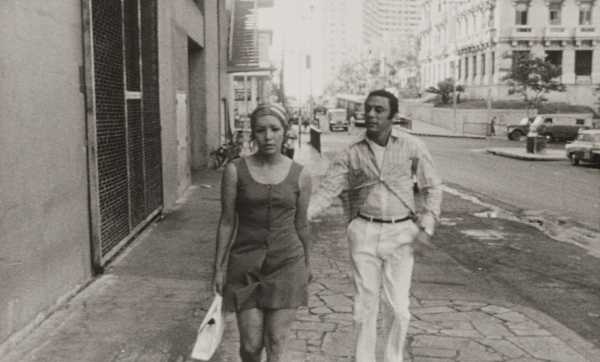

A still from “One Way or Another,” from 1975.Courtesy Criterion Collection

One of the prime virtues of Gómez’s work is its liberation of the voice. Although her on-camera interviews may sometimes be affected by regime censorship or self-censorship, she nonetheless succeeds in getting people from many backgrounds and walks of life to speak copiously about their experiences and observations. There’s none of the inhibition (or, perhaps, none of the prejudice) that tends to render working people steadfastly silent in American movies, perhaps because, in such films, there’s no overtly acknowledged class distinction between the filmmaker and her subjects. However, in her 1972 documentary “My Contribution,” about women in the Cuban workforce, Gómez uses overt, modernist disjunctions to draw attention to the class differences that nonetheless persisted in postrevolutionary Cuba. Without being openly dissident, she creates a critical cinema in both style and content. The film brings together her principal themes, of racial diversity and feminist consciousness, in a form that’s as frank as the discussions that she elicits.

As the title of “My Contribution” suggests, the short is not an observational documentary but a participatory one. Gómez, as a filmmaker, is part of that workforce, too, and she puts herself on camera among the women she interviews. Expressly repudiating the directional relationship of interviewer to subject, Gómez sits in a circle with three other women—an industrial designer, a journalist, and a scientific researcher—who discuss the obstacles that women face in their efforts to work. The main two barriers are the traditional role of homemaker and mother which they’ve been raised to fulfill and the “machismo” of men who expect this of them—an attitude that, as one of them notes, is largely instilled in men by women themselves. They see education as central to effecting changes in consciousness, but the journalist points to an inherent “contradiction” that this involves. She herself could pursue her own education only because her stepmother took care of the home. The scientist declares that, to avoid the trap, she’ll never marry or have children.

A title card announces “end,” but this isn’t the end. Another title card pops up, “A Report on a Cine-Debate,” introducing an extended scene in a movie theatre in which a different group of women watch the preceding sequence and discuss what they’ve seen. It’s a method pioneered in 1959 and 1960 by Jean Rouch, in his docudrama “The Human Pyramid” and in the documentary “Chronicle of a Summer,” but Gómez pushes it to an extreme of contentiousness and critique, heightening and reframing the conflicts and contradictions (both personal and ideological) of women’s lives in Cuba.

The second group of women seem older and less educated, and they call out the assumptions of educated women. One woman criticizes the scientist because she “only explains what she wants, her dreams, her desires, her anxieties.” Another chimes in, wondering what would happen if all women avoided having children, and adding, “She won’t have suffered for those children. And that is what life is about: suffering, love, laughter, all of that.” These working women declare that what’s needed is practical change in the domestic sphere. Men must take an equal role in housework and child-rearing, in order to put an end to the “slavery” that women endure at home. For that to happen, men should be taught that a husband who helps out “does not lose his masculinity for doing so” but, rather, is thereby “more valuable as a man!” One woman calls on media to take a leading role in presenting “new ways in which men should behave with women.”

A still from “My Contribution,” from 1972.Courtesy Criterion Collection

Such new forms of behavior and new ways of thinking are exactly what Gómez brings to light in her feature, “One Way or Another.” The opening credits trumpet its blend of documentary and fiction, labelling it “A film about people, some fictitious, some real,” and then listing a group of actors followed by a group of “real people.” The characters at the center of the drama are a young couple, Yolanda (Yolanda Cuéllar), an elementary-school teacher, who is light-skinned, and Mario (Mario Balmaseda), a Black worker in a bus factory. Their romance is anchored in a dialectical companionship in which they reveal and discuss the stories of their lives—lives that, as Gómez shows, are deeply established in the political and social practicalities of their neighborhoods and their times. Mario is embroiled in a conflict at his factory that’s debated in a workers’ assembly that he takes part in. Yolanda is frustrated by the difficulty of persuading poor and struggling parents to get their children to take education seriously. In one of a number of documentary asides, Gómez amplifies Yolanda’s struggle with sequences that show the demolition of slum neighborhoods and the construction of modern housing and which expound on the history of proletarian marginalization, rooted, Gómez asserts, in the capitalist necessity of unemployment. The result of this history is “inertia”; thus “antisocial attitudes within the revolution” persist.

Yolanda grew up in an economically comfortable home, and her path to her profession was untroubled. Mario, who grew up poor, grew up in the streets, shirked at school, and “enjoyed life.” Although he managed to win a scholarship, he abandoned his studies, intent instead on becoming a ñañigo, a member of an all-male, predominantly Black, secret society called Abakuá. Gómez provides another documentary interlude about Abakuá’s history—founded by formerly enslaved Africans, the group later grew to encompass the country’s Creole population, too—and its role in perpetuating a deep-rooted code of machismo.

Both protagonists have, in effect, centrifugal and centripetal conflicts. Yolanda finds herself increasingly at odds with colleagues because of her impatience with poor families’ unshakeable distrust and anomie. Mario finds himself in a conflict between friendship and duty. His friend, an outgoing and womanizing colleague named Humberto (Mario Limonta), leaves work on the false pretext of a family emergency in order to visit a girlfriend—and admits his lie to Mario. When Humberto, brought before the workers’ tribunal, brazenly repeats the lie, Mario is torn. Humberto pressures him to keep silent but doing so would mean betraying his communitarian principles. The code of machismo that binds Mario to his friend—and to his friend’s arrogantly sexual presumptions—is also a source of conflict between him and Yolanda. Even as she must recognize her economic privilege in order to contain her otherwise admirable candor and to approach her poor pupils’ families with patience and understanding, she presses him over his macho presumptions. Mario must choose between his bubble of male privilege and a new, revolutionary consciousness. (One of the film’s “real people,” Guillermo Díaz, a musician, a former boxer, and a convicted killer, plays a major role in Mario’s enlightenment.) Yet, not to put too fine a point on it, “One Way or Another” is centered on the revolutionary virtue of informing, even on friends.

If there’s an inherently didactic element to Gómez’s intricate interweave of documentary and fiction, it’s nonetheless a realistic didacticism. It reflects the prevalence of ideological discussion in Cuban daily life at the time—in education, propaganda, and in exactly the kind of workplace debates that are filmed. It also feels true to the characters’ mind-sets—the ideas, emotions, and motives (whether conscious or unconscious) at work in their lives. The sort of revelatory artifice is exactly what is so often missing from American movies, which, despite ostensible naturalism, lack the feeling of authentic contact with reality—especially of inner realities—which is so abundant in Gómez’s work.

Getting her start in film by the age of twenty, Gómez displayed the virtue of precocity. From an early age, she was involved in the wider world, dealing with professionals and bureaucrats, seeing and negotiating the practicalities of power, while also shaping her technique, forming her ideas, and expanding her realm of experience. “My Contribution,” her first great film, is thus the result not just of a decade of artistic development but, even more, the development of a cinematic world of her own—an entire complex of themes, tones, styles, and passions that she could put to the test in the world at large. Gómez, with her blend of documentary and fiction, of drama and intellectual analysis, devised a new cinematic method, which she used to express a powerful vision of her country, her time, and her own place in both. With its enthusiastic but critical portrait of Cuba’s revolutionary ideology and postrevolutionary order, her work exemplifies an ideal fusion of analytical, personal, and empathetic cinema. It exposes the framework of drama even while expanding it and takes a comprehensive yet dialectical view of individuals and society, rendering them not exclusive but inextricable, not fixed in identity but interconnectedly active and mutable. Just as Gómez, having died so young, is fixed in history as forever a young filmmaker, so her work continues to embody cinematic youth, even today. It’s a youth that few filmmakers working today have attained. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com