Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this storyYou’re reading the Goings On newsletter, a guide to what we’re watching, listening to, and doing this week. Sign up to receive it in your inbox.

Beguiling blends of fiction and nonfiction are the highlights of this year’s edition of the New Directors/New Films series, at Film at Lincoln Center and MOMA, April 2-13. “Fiume o Morte!” (April 4-5), by the Croatian filmmaker Igor Bezinović, is a novel approach to historical drama, realized with daring, skill, and sardonic wit. After the First World War, the Croatian town of Rijeka was invaded by Italian nationalists led by the poet Gabriele D’Annunzio, who, between 1919 and 1921, turned the city, under its Italian name of Fiume, into a proto-Fascist dictatorship much admired by Benito Mussolini. To recount the regime’s rise and fall, Bezinović gathers archival footage and still photos—and, largely via person-in-the-street interviews, assembles a cast of nonprofessionals to reënact events at the very sites where they occurred. The film’s self-deprecatingly comedic artifice nonetheless captures chilling details of an adventure that starts with a demagogue’s cult-like following and ends with bloody corpses. The movie powerfully conveys the eerie sense of experiencing history in the present tense.

The Croatian filmmaker Igor Bezinović’s “Fiume o Morte!”Photograph courtesy Lightdox

A literary detective story that’s rich in the fine grain of daily life, “Lost Chapters” (April 3 and April 5), by the Venezuelan filmmaker Lorena Alvarado, stars her real-life family: her sister, Ena; her father, Ignacio; and her grandmother, Adela Rodríguez. Ena, who’s twenty-five, is staying with Ignacio, a book collector specializing in the national literature. In one of his volumes, Ena finds a handwritten note about an early-twentieth-century Venezuelan author she’s never heard of, and, undertaking her own investigation, begins to doubt whether he really existed. Meanwhile, Adela, a former poet now showing signs of dementia, creates spontaneous poetry of poignant incongruities. Alvarado and José Ostos did the cinematography, and their keen sense of light, color, and tempo invests Adela’s tender observations and enigmatic digressions with drama and passion.

The documentary filmmaker Courtney Stephens directs her first quasi-fiction, “Invention” (April 5-6), in collaboration with the actress Callie Hernandez, who stars as Carrie, a young woman who visits a small New England town, where she claims the ashes of her late father, a doctor and a spiritual healer whose ambitious schemes came to naught. There, Carrie inherits the patent for his electromagnetic device and, to better understand it and him, connects with his collaborators, and enters the vortex of their conspiracies. The local, face-to-face action is amplified by clips of her father’s infomercials (taken from actual footage of Hernandez’s father) and by wry metafictional touches. With startling views of unspoiled nature, Stephens evokes vestiges of the philosophies of Emerson and Thoreau surviving the din of modern media.—Richard Brody

About Town

Off Broadway

Classic Stage Company’s revival of Alice Childress’s “Wine in the Wilderness,” from 1969, directed by LaChanze, is a character study about a character study: during the 1964 Harlem riots, Bill (Grantham Coleman), a hipster painter, works on a triptych about Black femininity; for his portrait of a “messed up chick,” he chooses the brash, needy, unsophisticated Tommy (Olivia Washington) as his model. She thinks she’s being wooed, only to discover that she’s an object of derision for Bill’s urbane friends. “Forget yourself sometime, sugar,” Bill says, but instead Tommy demands dignity and even love. Bill’s pivot to recognizing her value is wish-fulfillment stuff, but Childress’s own brush moves quickly over him, more interested in the details of a forgotten kind of woman and her beauty.—Helen Shaw (Through April 13.)

Dance

With their mix of authority and recklessness, Sara Mearns’s performances have been drawing audiences to New York City Ballet for almost two decades. She is a restless artist, unafraid to reveal her challenges: depression, hearing loss, burnout. All of this is poured into “Artists at the Center: Sara Mearns.” Part one is “Don’t Go Home,” a dance play, inspired by Mearns, written by Jonathon Young, and choreographed by the Canadian dancer Guillaume Côté. “I needed the piece to be personal. I needed it to be related to what I was going through in my life,” Mearns says of the work. Part two is a première by the former Alvin Ailey dancer Jamar Roberts, who performs alongside Mearns and the incisive Jeroboam Bozeman (also formerly of Ailey), among others.—Marina Harss (City Center; April 3-5.)

Jazz

Photograph by Ayana Wildgoose

A few days after his one-hundredth birthday, the saxophonist Marshall Allen began recording his début solo album. Starting in the nineteen-fifties, Allen worked alongside the cosmic jazz explorer Sun Ra, as a member of the Arkestra, and he’s led the ensemble in the creator’s stead since 1995. That is a larger-than-life legacy all its own, but “New Dawn,” released on Valentine’s Day, reveals that the titan isn’t yet done checking items off his bucket list. The music is clearly informed by his service in the Arkestra, but it is also resoundingly personal, culling from and synthesizing more than a half century of experience. As Allen steps out from under a large shadow, his grand solo turn is prime evidence that it’s never too late to set out on a new adventure.—Sheldon Pearce (Roulette; April 5.)

Broadway

First it was a club in pre-Castro Havana. Then, in 1996, a group of virtuosos from its heyday adopted the name for themselves and for their Grammy-winning album. Now “Buena Vista Social Club” is a Broadway musical (transferred from Atlantic Theatre Company). The book, by Marco Ramirez, rigs a narrative between the album’s recording and the club’s last hurrah, and at the show’s heart are songs from the album, many of them pulsating Cuban standards rich in subtext. Their melodies give way to bravura solos, including some flurry-fingered tres playing. Equally formidable, if less spry, is Natalie Venetia Belcon’s imperious, late-career Omara Portuondo, reluctant to sing again. But despite Saheem Ali’s sure-handed direction the storytelling sometimes stalls—a common fate for a jukebox musical, however lively its songs.—Dan Stahl (Schoenfeld; open run.)

Read Vinson Cunningham on the show’s Off Broadway première, in 2023.

Off Broadway

Photograph by Moritz Haase

It’s hard enough to navigate your personal life under regular circumstances. But when you’re also a slasher in Victorian London, weaving through the streets with your new wife’s disapproving father on your tail and a gaggle of local sex workers vying—successfully—for your attention, things can get really messy. BAM and St. Ann’s Warehouse present this havoc in “The Threepenny Opera,” which first premièred in 1928, in Weimar-era Berlin. Written by Bertolt Brecht and composed, with jazz and German-dance inflection, by Kurt Weill, the so-called “play with music” mixes the flamboyance of murder and lust with astute social commentary, in a Berliner Ensemble production, helmed by the seasoned Australian director Barrie Kosky.—Jane Bua (BAM; April 3-6.)

Movies

The Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira, who was born in 1908 and died in 2015, started his career slowly but made up for lost time, completing twenty-two features between the ages of eighty-one and a hundred and three. BAM is showing ten of them, in new restorations, including two exquisite ones from 2001. “I’m Going Home” stars Michel Piccoli in a tragicomic tale of an elderly actor who, after a grievous loss, throws himself into his work but finds his ability declining even as his sensibility remains strong. In the memory-film “Porto of My Childhood,” Oliveira blends archival footage, new documentary images, and deft dramatizations with his voice-over reminiscences of a bohemian youth amid the city’s cultural and natural splendors.—Richard Brody (BAM; March 28-April 3.)

Bar Tab

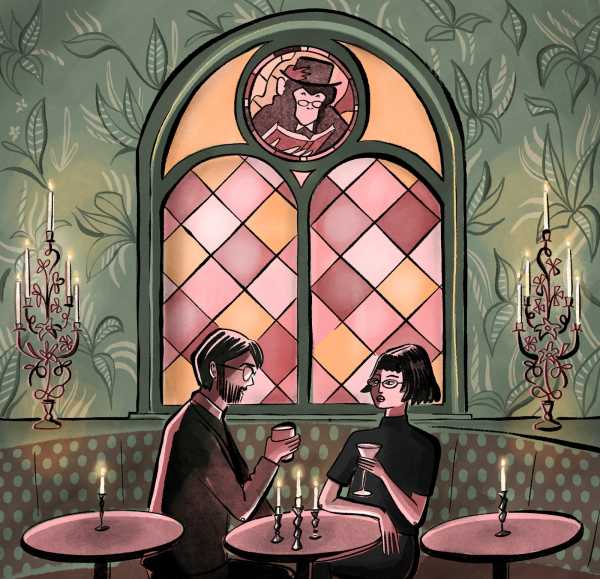

Rachel Syme checks out Baz Luhrmann’s theatrical new cocktail den.

Illustration by Patricia Bolaños

The Australian auteur Baz Luhrmann has his fans and his detractors; some are in thrall to his maximalist, hyper-saturated, bespangled visual style, and others find his frenzied work to be gimmicky and full of empty calories. Still, no one can deny that Luhrmann knows how to stage a party. He is at his best when engineering sybaritic revels: a night of rowdy cancan kicking at the Moulin Rouge, a champagne-drenched fête on Gatsby’s lawn, a phantasmagoric costume ball at the Capulet mansion. One could be forgiven, then, for assuming that Luhrmann’s first cocktail bar, Monsieur, would be a boisterous scene. But on a recent rainy Wednesday night, the mood inside Monsieur was surprisingly subdued. This may be a matter of scale. Monsieur, which occupies the former home of the gay dive bar Boiler Room, has an intimate feel, with room for just about two dozen teeny tables. Or it may be a by-product of aggressive art direction; Luhrmann and Catherine Martin, his wife and creative partner, fell in love with a stained-glass window in the space, and they designed the bar around a dimly-lit medieval theme, complete with Gothic candelabrum, Jacobean revival wooden furniture, and tawny tapestries. Scattered macabre ephemera include antique books, bronze statuettes, marble-like busts, and a suit of armor made of cardboard. The menu—full of twists on classic cocktails, such as an espresso Martini with a creamy glug of banana liqueur, or a Vesper enlivened with a bitter spritz of grapefruit oil—doubles as a set piece, with a full page devoted to the story of “Monsieur,” the bar’s fictional proprietor, a mythical “fabulist” and “trickster” who makes mischief with his sidekick, a chimpanzee named Tybalt. It’s quite the cinematic setup, but real life rarely feels as intoxicating as the movies.

P.S. Good stuff on the internet:

- How to do pleasuremaxxing

- A delicious recipe for your spring leeks

- Breaking the grass ceiling

Sourse: newyorker.com