Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The demonstrations that took place in Portland, Oregon, in the course of 2020 might constitute the most thoroughly documented social movement in American history. At least when I was there—in August and September of that year, on the tail end of more than a hundred consecutive nights of marches and rallies that often involved violent clashes with law enforcement—there sometimes appeared to be as many people recording the events as participating in them. One reason for this was likely self-interest. Identifying yourself as an observer afforded you a degree of protection against arrest and police brutality. Midway through Rian Dundon’s new photography book, “Protest City: Portland’s Summer of Rage,” we encounter a quintessential example of such vocational appropriation: a young man wearing a gas mask and tactical gear, with a GoPro device mounted on his helmet and a digital camera holstered on his hip. In his right hand, he holds a selfie-stick tripod attached to a phone; in his left, a homemade shield marked “PRESS.”

A protest photographer with a shield. August 20, 2020.

An injured protester is arrested by Oregon State Police outside the Portland Police Association. September 4, 2020.

Whether intentionally or not, Dundon’s book offers a welcome counterpoint to the so-called protest photographer, and a powerful defense of photography as a craft rather than a weapon or a tool for political activism. Dundon was a mainstay on the front lines of the demonstrations, and got as close as anyone did to the tear gas, rubber bullets, and batons. Yet the only equipment that he carried was a Fujifilm XF10—an unassuming point-and-shoot that’s compact enough to slip in a pocket. Aside from its inconspicuousness, the advantage of this camera, Dundon told me, is that it “slows things down.” Compared with a single-lens reflex or an iPhone, the XF10 generally takes more time to operate, forcing you to be more deliberate, and favoring moments of stillness over action. Dundon, in other words, is the antithesis of the live streamer, that increasingly ubiquitous chronicler of American unrest who captures whatever he encounters indiscriminately, with a premium on action. The results, in “Protest City,” are curated portraits and scenes of unusual intimacy.

Protesters form a shield line against federal police at Chapman Square. July 17, 2020.

A protester in a wedding dress and gas mask. July 18, 2020.

A man at work shows solidarity with marching protesters. June 1, 2020.

U.S. marshals rush a protester outside the Mark O. Hatfield United States Courthouse. July 18, 2020.

Nearly all of the images in the book were taken at night. In many of them, the XF10’s built-in flash brilliantly illuminates the immediate foreground while shrouding the rest of the frame in darkness. In recent years, more and more photojournalists have begun employing creative flash techniques for dramatic effect, and sometimes such hyper-stylized visual language can come off as overwrought, distorting reality or rendering it grotesque. Dundon’s approach, however, seems well suited to the subject at hand. The spotlighted isolation of the figures recalls actors on a stage, underscoring the theatrical aspect of the demonstrations. One protester wears a medieval-knight costume, another a hula skirt, a third nothing at all. Despite the showmanship, everyone in the book is gripped by genuine emotion—real indignation, fear, anxiety, conviction. Protests are performances, especially in Portland, but they aren’t only that. Dundon manages to convey this knotty tangle of artifice and authenticity.

Outside of the Multnomah County Justice Center, pig heads are burned as an effigy of the police. May 31, 2020.

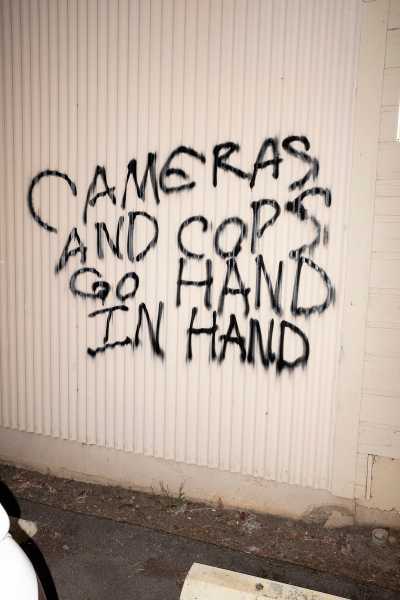

Anti-press graffiti. September 5, 2020.

An obvious challenge of protest photography, like war photography, is its absence of context, the severing of action from motivation and belief. In “Protest City,” we see broken windows, toppled statues, looted stores: we see, graphically, what the protesters have done. But why did they do it? In Portland, more than in Minneapolis or in other cities convulsed by the historic uprising for racial justice in 2020, the answer is complicated. The subtitle of Dundon’s book—“Portland’s Summer of Rage”—somewhat elides this complexity. The period covered begins on May 30, 2020, five days after the murder of George Floyd, but it continues until August, 2021. During those fifteen months, the rage that Dundon references was directed at a variety of targets: federal agents, the city’s Democratic mayor, the Portland Police Bureau, local foreclosure and eviction policies, juvenile detention, the Supreme Court, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Proud Boys and other Trump supporters who held their own provocative rallies downtown, annexation of Indigenous lands, the Presidential Inauguration of Joe Biden, capitalism, colonialism—the whole “system of oppression,” as one protester put it to me.

Under the pretense of safeguarding local businesses, the right-wing activist Chandler Pappas paces among the mourners at a vigil to mark the police killing of Kevin Peterson, Jr. October 30, 2020.

A broken bank machine. June 15, 2020.

The journalist Cory Elia sits in the back of a police car after being arrested at a protest near the Portland Police Association. June 30, 2020.

A home has been vandalized by protesters during altercations with neighbors near Portland’s East Precinct. August 6, 2020.

Of course, it would be unfair to expect a photography book to detail such a litany of grievances—and, by presenting his subjects outside of the ideological framework behind their activism, Dundon accomplishes something different. Without loaded classifications like “Black Lives Matter” or “Antifa,” the protesters become less novel and exotic, more mundane and recognizable. The diluted tones, high contrasts, and red-pupilled figures in “Protest City” combine to create a throwback aesthetic that also feels familiar. Dundon was initiated into photography as a high schooler, in the nineteen-nineties, by taking pictures of his friends skateboarding. Many people who grew up around that time will notice, in his work, the influence of skate magazines like Thrasher or Big Brother. This shows in Dundon’s raw, unflattering style of composition but also in his specific preoccupations: wanton vandalism, cheap tattoos, explicit graffiti—abrasions and abandon. This is not just the world of far-left activism. It is the world of wild, angry—and mostly white—urban and suburban youth.

In revealing this analogue between subcultures, “Protest City” rises from a visual record to a work of art. Dundon provides both a glimpse of a unique historical moment in American politics and an exploration of an American cultural phenomenon that might be more pervasive and longer-lasting.

Burn residue at Creston Park. February 21, 2021.

Sourse: newyorker.com