Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Fame after death can kill again. The historian knows this; the biographer knows this. No longer here to shape their own image, familiar figures become unknown to us. So many privacies now unguarded. The late James Baldwin, who died on the first of December in 1987, provides endlessly. You think, poring over his letters, that you are getting to know him better—the uncovered lover, et cetera—when the person you are getting to know better is yourself.

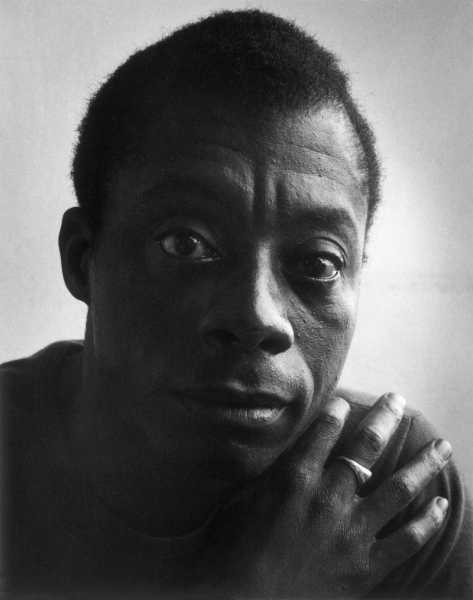

Portrait of James Baldwin, 1964.

Your feelings of orphanage, say. The modern picture of Baldwin is dominated by the retrospective veneration slant. He has become a cross between the preacher and the Daddy, composing a portrait of the segregated world through his seer’s gift for ice clarity—a depiction that comes at the expense of other aspects of his character. I have a hard time with, for example, “I Am Not Your Negro”—the 2016 Raoul Peck documentary, constructed from archival images and film—which I know to be an excellent exhumation of late-in-life Baldwin wrestling with his unfinished manuscript, “Remember This House,” a memoirist work spun out from his grief following the killings of Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr. What I bristle at is the film’s excision of Baldwin’s queerness, which means the excision of full love. Baldwin is the de-facto writer of the film; his writings supply the narration. But the voice reading them is that of Samuel L. Jackson, phenomenal and eclipsing—and straight. It manages to cancel out the strong aural memory we have of Baldwin the orator, to functionally unqueer him. What is left is the voice of the disambiguated prophet. Baldwin becomes the immortal speaker, always at service. He sermonizes over the terror of his world and of ours, as the archival gives way to contemporary images of Black Lives Matter rallies.

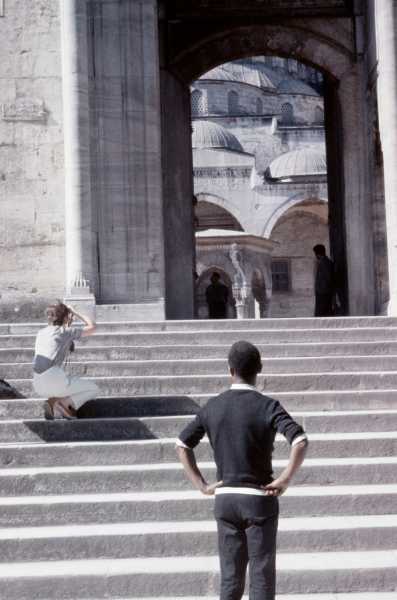

Baldwin and U.S. Navy sailors, near the Blue Mosque, in Istanbul.

Other treatments attempt biography through the display of letters. The centennial of Baldwin’s birth, this past year, saw no shortage of hymns, modulating the key to minor and rendering the arrangements slightly discordant. The New York Public Library took the route of institutional projection. Culled from an acquisition of some of Baldwin’s personal archive, two exhibits—one at the library’s landmark building, on Fifth Avenue, and the other at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, on Malcolm X Boulevard—emphasize how Baldwin fell in love with reading and thinking in the city’s libraries. In one paper, a draft of “Letter from a Region in My Mind,” Baldwin writes of “crossing Fifth Avenue on my way to the Forty-second street library, and the cop in the middle of avenue muttered, as I passed him, Why don’t you niggers stay uptown where you belong?” Again, Baldwin is speaking to us from the dead. Uptown, at the Schomburg, a shelter for the archives of twentieth-century Black intellectuals, the show—called “JIMMY! God’s Black Revolutionary Mouth,” in reference to the writer Amiri Baraka’s eulogy of Baldwin—made more intuitive sense. Harlem had been Baldwin’s origin place, the display of letters to his confidantes the stuff of homecoming. And yet papers under vitrine turn sterile. Transformation, let alone transformative understanding, cannot occur.

Sherbet seller, customers, and Baldwin at the Yeni Cami (New Mosque), in Istanbul.

So how do we get to Baldwin through something beyond the collection of artifact, an anti-interpretation practice that is plaguing the curatorial practices of some American institutions set nobly on protecting Black history? Notice that the exhibits never leave the domain of Afro-American-Christian adoration: God and prophecy do not exit the room. The singer-songwriter and bassist Meshell Ndegeocello, in her homage to Baldwin’s language and message, does more than venerate; she achieves active transformation. Baldwin himself believed that it is only in music, which “Americans are able to admire because protective sentimentality limits their understanding of it, that the Negro in America has been able to tell his story.” Ndegeocello’s suite “No More Water: The Gospel of James Baldwin” does with music what Baldwin did with writing, using his language in the construction of her work. The effect is to “give Baldwin back his body,” to paraphrase my colleague Hilton Als, whose 2019 exhibition “God Made My Face: A Collective Portrait of James Baldwin” is a cognate to Ndegeocello’s. Bringing together contemporaneous portraits of Baldwin with works conceived and made after his death, Als grasped both entities: Baldwin as he lived, and Baldwin as he affects us.

Baldwin inside the Blue Mosque.

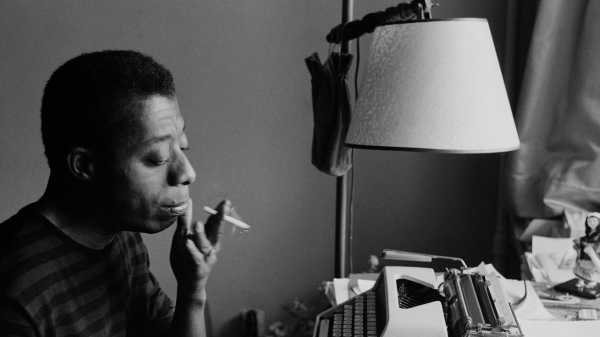

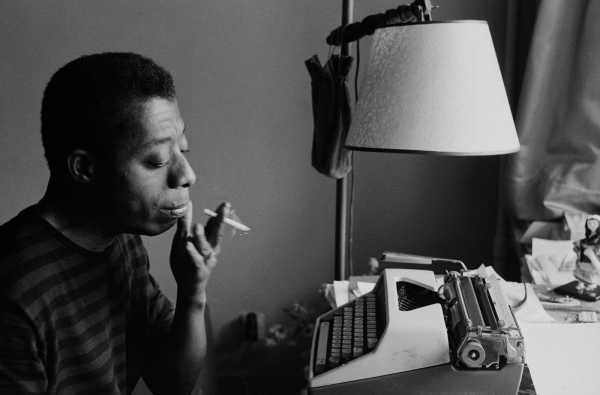

The new Baldwin photo exhibit at the Brooklyn Public Library’s Grand Army Plaza branch is not calling attention to itself, mounted as it is in the busy lobby and on the second floor. You may even miss it altogether. On display is a suite of photos that have not been seen by the general public—which is the obvious draw. But even what is known seems new. A famous photo in the collection shows a seated Baldwin at a typewriter in an enclosed room, cigarette in hand, some light emanating from a window. He is looking at his machine. Everyone in the world is looking at him. Most recognize this author’s photo but do not know its setting or its circumstances: it is an icon, a talisman. Baldwin is the archetypal author in the archetypal room, alone so he can look outward. It was Sedat Pakay, a young Turkish photographer and filmmaker and friend of Baldwin’s, who composed the photograph, and the room, Baldwin’s own in Istanbul, the on-and-off residence he took up from 1961 to 1971, precipitated by a psychic block that made writing arduous.

Baldwin at work on his novel “Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone.”

The text that weighed on him at the time of his arrival to Turkey was his novel “Another Country,” then unfinished. The turbulence of civil-rights America, too. Baldwin is said to have come to the residence of Engin Cezzar, a Turkish actor who played Giovanni in a workshop of a stage production of “Giovanni’s Room” in New York, completely spent. Baldwin in flight. We associate him with two countries. The land of his birth, the United States—in which he, a Black man who loved men—could not be physically or psychically safe. The land of his expatriation, France, where he experienced, first, a relative sexual and racial freedom, and, as he aged, a critical confrontation with his own Americanness. A kind of frustration with Baldwin is his alienation from African intellectuals, as he himself describes in his essay “Princes and Powers,” an analysis of the First International Congress of Black Writers and Artists, held in Paris, in 1956. And so his time in Turkey—in Istanbul, the port city that predated the creation of the “Western World” and the attendant pillaging of the “Dark Continent”—figures in the Baldwin narrative as a liminal space. This is the space explored in the Brooklyn Public Library exhibit, which is titled “Turkey Saved My Life: Baldwin in Istanbul, 1961-1971,” featuring photographs made by Pakay.

Baldwin at the steps of Yeni Cami.

It is a little surreal to see Baldwin looking out on the Bosporus strait. It is a little surreal to see his form, in profile, matching with the horizon of the Golden Horn. (Pakay was young when he became friendly with Baldwin, and his photos can convey an awed, staged quality; Baldwin, ever the photographer’s dream, plays along.) It is especially surreal to see Baldwin close to the Blue Mosque. Why? He is taken out of the Western-Christian context. A recent visit to Israel had disabused him of the propaganda representing that country as an intercontinental oasis of racial harmony. Baldwin flaunts his difference in the Eastern city, meeting babies, flirting with everyone, therefore making the city fit itself around his difference. Certain compositions diminish his Americanness, foreground his Africanness. He sits among smoking Turkish men, drinking Turkish tea, as my colleague Elif Batuman notes in a text for the exhibition, going on to describe “the obvious yet somehow thrilling realization that, while he was in Turkey, Baldwin consumed Turkish food.” The writer is a gravity-stealing subject. He had all his life wanted to be desired; he is Pakay’s love object, captured in crowds—a counter to the gravitas portraits we have of Baldwin from his American compatriot, the photographer Richard Avedon.

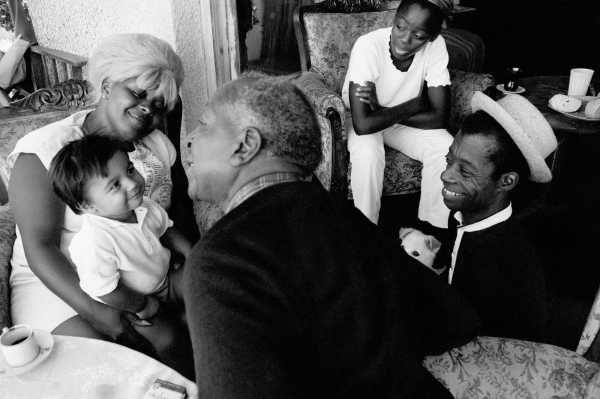

Baldwin was a social creature, practically drowning in friends. Some of Pakay’s photos have that life-style-magazine glamour. Here is Baldwin in his apron, preparing dinner for guests. Here he is smiling so widely he seems crazed, a man standing beside him, patting his shoulder. Visitors from the States come to him. Here they are eating at Baldwin’s home on the Bosphorus. Beauford Delaney was Baldwin’s mentor and the painter of my favorite portrait of him, “Dark Rapture,” an Expressionistic oil work in which Baldwin is an idealized nude, posing on a bed, flanked by two trees, his body swirling and melting with the landscape. Some twenty years after the painting, Delaney’s protégé is holding a salon across the Atlantic. Delaney appears in the photos, as does Bertice Reading, the actress, and Don Cherry, the oracular jazz trumpeter and composer.

Baldwin, Beauford Delaney, Bertice Reading and her children.

Baldwin said that Turkey saved his life; hence the name of the exhibition. There he completed “Another Country,” “The Fire Next Time,” and “No Name in the Street.” Magdalena J. Zaborowska, in her book “James Baldwin’s Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile,” reports deeply on the sexual and sensual aspects of Baldwin’s flight, too. It is interesting that he seemed to hoard the city from the page—that he protected Istanbul from the unsparing glare of his own pen. Privacy is a theme in Pakay’s stronger portraits. The standout is of Baldwin in bed, crumpled beneath his sheets, inching so close to the edge of the mattress that he may be touching the wall, that famous face totally obscured, a sort of counterpoint to “Dark Rapture.” Make no mistake, the Turkish knew of Baldwin; his arrival in Istanbul made the papers. But he could live more openly there than he could in Paris or New York, where his legend was taking over his life. In Pakay’s short documentary “James Baldwin: From Another Place,” filmed in the early seventies, Baldwin is nearly that nude, this time in life. The film opens with him tumbling out of bed in nothing but white underwear. This is a desirable body, and clearly desiring. He dresses, he makes his way through the city. He speaks of the vantage of the expatriate. He can see his country from that distance. He has loved and he has loved men, he says. He has never considered himself to be a leader, he continues, more a witness.

Baldwin on a rowboat in the Golden Horn.

In 1969, Baldwin directed a piece of theatre, “Fortune and Men’s Eyes.” John Herbert, a Canadian playwright, had made a semi-autobiographical work about his gayness and his experience in prison—two confinements. Baldwin staged the play in Istanbul, recruiting Cherry to compose music for it and persuading male actors to take up drag. He sublimated his own prison experiences—Baldwin spent eight days in a French jail, charged with petty theft—in his production. We have a photograph of the performance, actors pushed momentarily out of the gender script, the man who directed them nowhere to be seen, deep in the wings. In Pakay’s film, he approaches a book stand, where he finds a Turkish translation of “Fortune and Men’s Eyes.” He picks up another book and lifts it to the camera—“The FBI Story”—and smiles. Baldwin lived in America even when he was gone; the F.B.I. had a file on him nearly two thousand pages long. The Baldwin of the Brooklyn Public Library exhibit is separated from the Baldwin who was hunted. He floats in time. It is a thing we have to tell ourselves, retrospectively, that when he was away from America, he felt total and purgative relief. That America was killing him. And, wherever he went, America was always there.

Reading and Baldwin in Kilyos, on the Black Sea.

Sourse: newyorker.com