Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Lev Rubinstein, who died in Moscow on Sunday, at the age of seventy-six, invented a new kind of poetry and also, perhaps, a new way of living. Rubinstein, who spent years working in a library, wrote his poems on library catalogue cards. Some cards contained just one line, some a verse or a passage; some of the verses rhymed; a stack made a poem. Rubinstein read his poems aloud, pausing between cards. There was a distinct rhythm and order to the cards and the lines on them, underscored by the medium: cards, unlike lines on a page, could be shuffled, mixed up, accidentally placed out of order, and this made the listener notice how clearly and intentionally each poem progressed from card to card.

A 1995 poem titled “This Is Me” was quickly decipherable as a tour through the author’s family-photo album:

1.

This is me.

2.

This is also me.

3.

Me again.

4.

My parents. This must be Kislovodsk. The caption says “1952.”

5.

Misha with a volleyball.

6.

Me with a sled.

More characters appeared, with ever odder captions and details. And then the narrator returned.

113.

And this is me.

114.

And this is me in shorts and a T-shirt.

115.

And this is me in shorts and a T-shirt hiding under a blanket.

116.

And this is me in shorts and a T-shirt hiding under a blanket sunning on a grassy knoll.

117.

And this is me in shorts and a T-shirt hiding under a blanket sunning on a grassy knoll and my marmot is with me.

This, we know, could not be a photograph. But words have an inertia of their own; one stock phrase hooks on to another, forming a rhythmic chain that has a distinct mood and a clear subject—language itself. The shorts and the T-shirt and the blanket and the hiding come from a Soviet childhood—so the language indicates. The grassy knoll and the sun come from an idyllic summer that may have happened only in the imagination. The marmot comes from a poem by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, put to music by his friend Ludwig van Beethoven, and references poor children who wandered medieval cities with their domesticated marmots who aided them in begging. The experience of reading or hearing the verse—the catalogue card—is akin to looking at someone’s black-and-white childhood photos: none of it is decipherable, all of it is familiar.

Rubinstein was a founder of the Moscow conceptualist movement in art and literature. Born in the nineteen-seventies, this movement was a liberatory, fuck-you response to Soviet totalitarianism. The regime had long since appropriated everything: every minute in the day, every square centimetre of space, every word in the language, every color in the palette, every note on the scale. Artists and writers who had resisted the Soviet regime in previous decades had tried to carve out niches that were, possibly, unreachable to ideology (lyrical poetry) or to follow Western trends in art (abstract painting or French New Wave-style cinema). The Moscow conceptualists adopted the opposite tack: they took the bureaucratic language and the desolate landscape of Soviet totalitarianism and made fun. A series of works was called “collective actions.” These were elaborate group activities scripted in dense Sovietese. Tiny audiences drawn from the Moscow intelligentsia travelled to some designated spot in some unremarkable wood to take part. They concentrated on purposeless tasks, making a joke of time, space, and fear. Soviet totalitarianism couldn’t exert its violence on language if people laughed at what it did to language. “We acted as though the Soviet regime didn’t exist,” Rubinstein used to say.

Soon after the Soviet Union collapsed, Rubinstein stopped writing poetry. Much later, he wrote to another Russian poet, who felt that his own humorous writing might be inappropriate during the war with Ukraine, “Don’t ‘give up on poetry.’ Not that you’ll be able to do it until poetry itself ‘gives up’ on you.” In the nineties, poetry seemed to give up on Rubinstein even as fame—books, awards, prestigious writing residencies—found him. In 1996, he joined the staff of Itogi, a new weekly news magazine in Moscow. The editors wanted to create a front-of-the-book section modelled on The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town. Rubinstein pioneered the genre in Russian, in a shorter, lighter form: a passing observation.

Years later, he told a young interviewer that the best prose writing was like tryop—the Russian word for idle talk—as long as the writer knew how to engage in this kind of talk, and as long as the writer was a master of the disappearing art of telling stories in real life. But Rubinstein didn’t exactly tell stories—he painted scenes. In these scenes, any action, plot, or character was secondary to the real protagonist: language. One story went something like this. A woman, smelling heavily of vodka, came close to Rubinstein and hissed, “I’m going to fucking kill you.” Rubinstein appraised the situation: it was the middle of the day, and there were many people around. “All right,” he said. “Go ahead.” The woman replied, “Go fuck yourself.” In another story, Rubinstein went to a store. There was a puddle in front of the meat counter. “I’m sorry,” the saleswoman behind the counter said. “We had a lady in here who pissed herself.” The story was about the combination of “lady” and “pissed.”

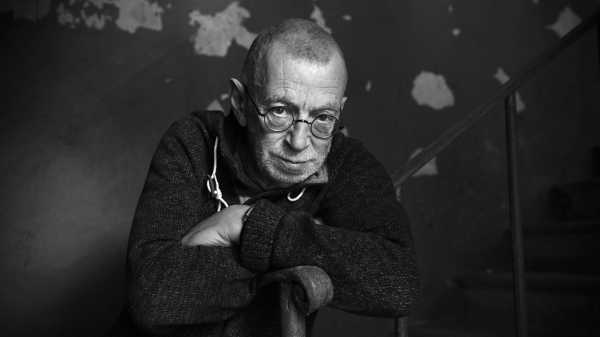

Rubinstein and I started working at Itogi on the same day. He was in his forties. I was in my twenties. We became friends. As he aged, his friends’ kids and his kid’s friends grew up and became Rubinstein’s friends. As I aged, I thought that I wanted to be like Rubinstein: an ageless boy, with friends of all ages. He possessed a style of Bob Dylan-level effortlessness—jeans or corduroys, sweaters, excellent scarves, and good shoes. From decade to decade, his hair and beard became shorter and his eyeglass frames less chunky, but the general silhouette and the unmistakable sense of coolness remained consistent.

When Rubinstein arrived at Itogi, he worried that he’d run out of ideas, or that he didn’t have the discipline to engage in writing as wage labor. For the first few years, he seemed surprised every time he produced an essay—always ahead of deadline—for that week’s issue. He’d print it out and hand it to his editor with the words “I recommend it. A very interesting story.” He showed up for meetings half an hour early. (Everyone else came late.) He never left anything on his desk. (Everyone else left things all over the place.) Later, when we spent a couple of years sitting at adjacent desks at a different magazine, Rubinstein would arrive at the same time each morning, place a notebook and a book or two on his desk, work until four, then supplement the still-life on his desk with a small bottle of vodka and continue working until six, whereupon he would commence his social life.

In a remembrance, the poet Sergei Gandlevsky, one of the people who knew Rubinstein best, called him “implausibly sociable.” He was not indiscriminate—he didn’t suffer fools, careerists, and narcissists—but he had a vast range of social possibilities. He accepted every birthday-party invitation, most dinner-party invitations, and many invitations to go grab a drink. He was tiny—maybe five feet five—and, unlike many other small famous people, he had a light, airy presence. He rarely talked about himself, except to share an entertaining anecdote, usually about language, occasionally about his childhood, though that, too, was always, at least in part, about language. Like the story about how he found out that his mother didn’t know everything: he asked her what was longer—an era or an epoch.

Within a year of Vladimir Putin’s ascent to the Presidency, Itogi was taken over by a state-owned company, and Rubinstein, like everyone who worked there, lost his job. Over the next twenty-one years, he worked for more than half a dozen other independent Russian publications, writing his very short essays. They were no longer about strange or amusing incidents in the life of the city and its language; they were about trying to live with dignity and decency in a country such as Russia was becoming.

In a recent letter to the writer Boris Akunin, who lives in exile in France, Rubinstein wrote:

You keep writing about Russia. I understand that. But recently I have sunk into a state of such desperate negation that I can hardly even pronounce that name. . . . I hope that passes. But for now, that’s how it is.

In 2011 and 2012, when hundreds of thousands of Russians came out to protest Putin’s regime, Rubinstein went to every march and every demonstration. In our conversations, he wondered if a strategy like the one of “pretending that the Soviet regime didn’t exist” could be used again. But, as the Kremlin cracked down, and especially after Russia invaded Crimea in 2014, it became increasingly clear that no one who turned their back on the regime would be left alone for long. People started to emigrate. Rubinstein stayed, explaining that he had long since decided that he would leave Russia only if he was forcibly exiled or if his life was threatened. And then poetry returned to him. He did not, for the most part, write library-card poems; his new work was more traditional in form, though it still contained chains of clichés, almost invariably to heartbreaking effect.

In 2022, following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Rubinstein’s circle seemed to shrink catastrophically. Many of his contemporaries left. Their children left in even greater numbers, taking with them their own children, who were going to grow up to be Rubinstein’s friends, too. He stayed, because, as he had written, a few people were still there, and because he loved his city, and, I think, because he was afraid to leave. He had travelled widely, had been fêted at literary festivals in Western Europe and the United States, but what he needed was not travel—it was a home city where he could talk to a lot of people, and where he could hear a lot of people speak his language and notice how they spoke.

Rubinstein created a rigorous writing practice on Facebook. He posted daily, in one of three genres: excerpts from an almanac called “The Entire Year”; compilations of often macabre headlines from Russian media; and short chapters from a book in progress, a memoir of his childhood. The memoir was populated with communal-apartment neighbors, women who occasionally slipped into Yiddish and always practiced peculiar logic, little boys who smoked, and a mother whom Rubinstein clearly still missed. I found these posts reassuring, as though they meant that this period of darkness would pass, and that Rubinstein, ageless as he was, would still be there when the war ended. We’d drink together again. He also wrote regular columns for Republic, one of many Russian online publications produced in exile. His last one, published on January 4th, was a New Year’s greeting: “I wish us all a dose of friendly curiosity, particularly in relationship to the other, the strange, the new. Yes, the new. In the phrase ‘New year,’ familiar to us from childhood, the key word, I insist, is ‘new.’ ”

The last lines of his last poem, posted on Facebook on January 2nd, were as frankly dark as anything he’d written:

The times are such that there is no standing up

Or lying, or sitting down, screaming, or cursing.

You wake up in the night because your bed

Is sinking, and you are sinking with it

On January 8th, he left his apartment to go to the post office. A car speeding down a nearly empty street hit him in the crosswalk. He flew over the hood and the roof of the car, almost as if he were jumping with his usual lightness, before falling to the ground. He was rushed to the hospital. Thousands of people in different parts of the world prayed for his recovery and stayed glued to their various screens awaiting news. Five days into the hospitalization, news came that Rubinstein had died. Then this information was retracted. “He is still alive,” his doctor was quoted as saying. I thought Rubinstein would find the incident and the phrase funny, because it’s redundant. Anyone who is alive is still alive, alive until we die. I thought Rubinstein might use this story in an essay, as a story about life and language. But he never regained consciousness.

On Wednesday, hundreds, perhaps even thousands of people attended a memorial service in Moscow. As it turned out, there were still a lot of people there who needed Rubinstein.

In “Life Is Everywhere,” one of Rubinstein’s library-catalogue-card poems, from 1986, the repetitive dialogue seems to capture a conversation between, perhaps, an actor and a movie director, or a poet and his superego:

1.

“O.K. LET’S BEGIN . . .”

2.

“Life is given to us humans only once.

You be careful, dear, don’t let it slip away…”

“O.K. KEEP ROLLING . . .”

3.

“Life is given to us humans for a reason.

Be good, my friend, and worthy of your life . . .”

“GOOD. CONTINUE . . .”

4.

“Life is given to us humans for a reason.

You should really try, my dear, to treat it well . . .”

“STOP!”

5.

I can’t hear a thing. All this noise. Give it a try now—perhaps it’ll work. . . .

6.

GO AHEAD!

7.

“Life is given to us humans for a moment.

Go and do as many good things as you can . . .”

“KEEP GOING . . .”

Over the next dozens of cards, the poem rose and fell, became strange and then mundane again in a tempo that grew familiar, as though it could go on forever—until the last card.

59.

“Our life is rushing on

Over waves and winds.

Here is our endless grief”

“STOP!

FINE. ENOUGH. THAT WILL BE ALL. THANKS.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com