Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The interior of Jeff Bridges’s garage, in Santa Barbara, California, has the ramshackle ease of an extravagant dorm room: a tiger-print rug, a potter’s wheel, guitars, a rogue toothbrush, taped-up printouts of ideas he finds provocative or perhaps grounding (“Enlightenment is a communal experience”), and piles of books, from Richard Powers’s “Bewilderment” to “Who Cares?! The Unique Teaching of Ramesh S. Balsekar.” A black-and-white portrait of Captain Beefheart, incongruously dressed in a jacket and tie, hangs on a wall near an electric piano. When I arrived, on a recent afternoon, I did not take note of a lava lamp, but its presence didn’t feel out of the question. A salty breeze rustled some loose papers. Bridges was wearing rubber slides and a periwinkle-blue cardigan. He excitedly spread out a large furry blanket on a recliner and invited me to sit down: “Your throne, man!” he said.

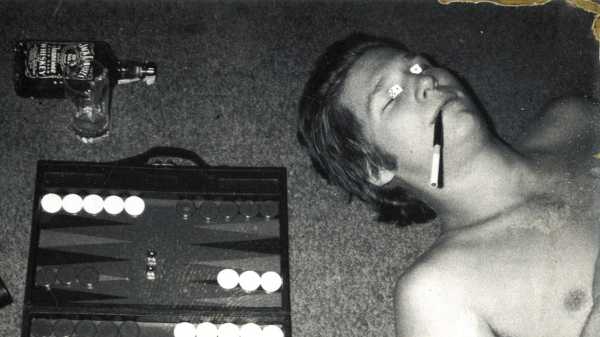

Earlier this month, Bridges released “Slow Magic, 1977-1978,” a series of songs he recorded when he was in his late twenties, an emergent movie star, and involved in a regular Wednesday-night jam session with a coterie of musicians and oddballs from the West Side of Los Angeles (the jams were organized by Steve Baim, who attended University High School with Bridges; they took place in various beach houses and, occasionally, at the Village, the recording studio where, around the same time, Fleetwood Mac was making “Tusk”). “Slow Magic” is great and also bonkers. On “Kong,” Bridges recounts a story line he pitched for a potential “King Kong” sequel (in 1976, Bridges starred as the long-haired primatologist Jack Prescott in a “Kong” remake produced by Dino De Laurentiis); the track features animated narration from the actor Burgess Meredith, and its lyrics are centered on the revelation that Kong is actually a robot. “It’s a sad story, but he was just a monkey machine!” Bridges wails in a tottering falsetto. (The idea was rejected.) On “Obnoxious,” a weirdly tender song about feeling sad and having a stomachache (“I went to the bathroom / And threw up”), there are echoes of Frank Zappa and the Band. Sometimes one also senses the influence of quaaludes.

What I like most about the record is how social it feels: friends in a room, being dumb, intermittently (even inadvertently) doing something miraculous. “When recording technology kept improving, I said, ‘Oh, I don’t need anybody! I can do this all by myself,’ ” Bridges told me, leaning back in a lawn chair. “That was kind of a trap, because even just reading the instructions took me out of the creative thing. I did some stuff that way, and it was fun, but it got me out of playing with live musicians.”

Bridges is affable, generous, enviably mellow. We watched YouTube, ate salad by his pool, and talked for several hours about art and love, and the funny ways they occasionally overlap. “Slow Magic” is available on vinyl for the first time this weekend, for Record Store Day, via Light in the Attic Records. This conversation has been condensed and edited.

When Matt Sullivan, a co-owner of Light in the Attic, first sent me the album, he called it “surreal.” I remember thinking, I’ve heard some pretty out-there records. I was very cocky about its potential weirdness! Then I put it on, and, man—I’ve never heard anything like this before.

That’s great to hear! That’s what we like—fresh, right? Fifty years old and fresh! A couple years ago I had cancer, and then I had COVID, and the COVID made the cancer look like nothing. Chemo had stripped me of my immune system. I was right at the door, you know? People didn’t know if I was gonna make it. And I thought, Hey, look, Jeff, you’re seventy-three. Do you have the juice to go in and polish all these tunes that you have? Why not just put ’em out? There’s so much content now, or whatever they call it—in one sense, it’s kind of a good thing, because everything becomes less precious. So I thought, Well, this kind of bookends the whole thing. This release is in the same spirit as the Wednesday-night jams.

In the past, you’ve released music that feels a little more conventional, or at least more tethered to genre. But you’ve also done a few things that fall somewhere in between the more produced Americana of, say, “Be Here Soon,” an album you made with Michael McDonald and David Crosby, and the very wild psychedelia of “Slow Magic.” I’m thinking of the “Emergent Behavior” series, on your website, where you pair these fairly raw acoustic songs with some trippy visuals.

The phrase “emergent behavior” came to my attention when I made this movie called “Living in the Future’s Past,” about our environment and global warming. It’s not so much pointing fingers at the bad guys. What we wanted to do was to address the question: Why are we behaving this way, when we know what’s going on?

Well, that’s sort of the big human question: Why do we do things that we know are bad?

It’s so interesting, you know? Emergent behavior is the principle of a superorganism. The murmuration of birds, for instance. You see the shape, how they all go like this. [Bridges swoops his hand to one side.] Now why are they making that shape and not some other shape? So then there’s the superorganism of humanity—we’re all on this planet, and we’re not doing that, we’re doing this. Why? One of the aspects of emergent behavior is that if you take one of the small organisms that make up the superorganism, it will tell you nothing about the superorganism. It won’t tell you anything about the why. So there’s something goin’ on that we’re not privy to. And that gives me a very hopeful feeling. These mysteries happen. You might experience this as a writer, where it’s doing you instead of you doing it. That’s the sweet spot, isn’t it?

But what is that? Is that . . . God?

Certainly. The God who is unutterable. You put a name on it and it becomes the golden calf, you know? It’s not any of your concepts—it’s something outside of that. When creativity is going down, you acknowledge that, and you try to get out of your own way. You’ve got to let the ego just go sit on the bench, and just hear what wants to be done through you. Man, talking about getting out of the way—another person who is so responsible for “Slow Magic” is this guy, Keefus Ciancia. I met Keefus through T Bone Burnett. He was a player on the album I did with T Bone. We became fast friends. It’s interesting, in life—you have all these opportunities that you’re offered, and you either take ’em or you don’t. It’s so interesting, isn’t it?

It’s actually the only interesting thing.

I’m thinking of a Leonard Cohen song. Are you a fan of Leonard Cohen?

Of course.

Do you know the song “Waiting for the Miracle”? Isn’t that a great song? Like, we’re waiting for that silver bullet when the miracle is here, baby! It’s right here! So this new album, this fifty-year-old album that’s about to come out, is the same kind of thing. Every once in a while life seems to invite me to do something off-kilter, and I just can’t help it. I’m drawn to it. Anyway, Keefus calls me up a little while later, years later, and he says, “Say, do you want to go into a studio? Just bring some of your tunes and see what happens?” So I brought this little cassette from the seventies, and he loved it. Without telling me, Keefus sent it to Light in the Attic, and they wanted to make an album. I said, “What, they want to redo these?” “No, no! Just put it out.” I said, “You’re kidding me! It’s just full of clams! It’s so rough.”

But that’s really the pleasure of it.

Often you’ll have an album that’s a success, and then maybe a year or two later they’ll have the “making of” album, where you hear all the rough stuff. This is kind of like doing that in reverse. This is letting all the rough stuff out, and if I or anybody else wants to polish ’em up that’s something else.

For me, these songs are beautiful, and often quite funny, but the thing I find the most intoxicating about them is how loose and convivial this music feels, how unselfconscious. We lose our ability to be that way as we get older. I have a three-year old daughter, and she is very, very tapped into the lunacy of existence. This record spoke to her.

What do you and your daughter think of “Space 1” and “Space 2”?

Two thumbs up!

Those were very Wednesday-night jam. The leader of those things, a guy named Steve Baim, he had certain rules, and one was that we didn’t want any songs. Improvisational singing was encouraged. But we weren’t gonna do “Twist and Shout” or something. It wasn’t like that. He also encouraged everyone to play instruments they didn’t know how to play.

That’s what kids do, too.

You just don’t know where it’s gonna go!

Joan Baez does this thing where she’ll draw upside down and with her nondominant hand, because she feels as though it frees her from being critical, or from trying to make something perfect. In the liner notes for “Slow Magic,” there’s a photo of you playing a piano with your mouth.

Well, that was the thing about the Wednesday-night jams. It was creating this safe place, you know? It’s the same kind of thing when you’re making a movie. That’s what I look to a director for, to create a vibe that we’re all set loose in. Every director has a different approach in how they create that vibe. But I’ve gotten a chance to work with some real masters. I’m thinkin’ Hal Ashby was like that. [My brother] Beau did Hal’s first movie, I did his last movie—we bookended his whole career. Gosh, what a master. And he was all about improvisation and getting out of the way. Let’s see what wants to be born here.

The trick is figuring out how to really clear space for that, because I think we do want to get out of the way—every human consciousness seems to crave a break from itself from time to time.

How do you put yourself in that position? How do we create instances that call on us to do what you’re talking about? To get out of the way? I consider myself a very lazy person. But then I say, “Look at all the stuff that you’ve done, man.” But I’m just—I’m so . . . I’m so lazy. [Laughs.] The high in life, for me, is intimacy. I’ve been married for forty-eight years. We’ve known each other for fifty years. And it gets better and richer and all of that. Then there’s intimacy with yourself, where you don’t get too mad at yourself for being lazy. [Laughs.]

But one of the answers to creating this space is just showing up. How do you practice that? It’s like the Cohen song. It’s always available. It’s always there. One of the things, when I was sick, I tried to study health. And one of the things I got involved with was Wim Hof. He’s also known as the Iceman. He’s all about breathing and going into very cold water. We resist that. We don’t want to be cold. But to be cold on purpose is a different thing. I made a little tiny adjustment with my relationship to cold. You get in and—“I’ve gotta get out!” No, this is just a feeling. Dig the feeling. It’s not gonna last forever.

That sounds hard.

Not as hard as you’d think, in a weird way. Yeah, you’re cold. But you don’t have to jump out. I don’t have to do what I’ve been programmed to do. Then, all of a sudden, I have another relationship with coldness. You can have that with everything. The main thing I realized when I was sick was that the miracle in that Leonard Cohen song is always going on. But that closeness to mortality, death—wow, what a gift. You can get into fear of the unknown. That’s an interesting one. The unknown is kind of a beautiful thing, too.

It sounds like you’re describing the spirit of the Wednesday-night jam.

You’re not doing it, it’s doing you. I’ve been exploring this idea of willpower recently. This guy, [Robert] Sapolsky, have you gotten into him at all? The idea is: Is willpower an illusion? Are you really making these choices? All that stuff. You think, Oh, I’m doing this—but how much? My current thought is that we’re doing it all together. Life seems so paradoxical, doesn’t it? Christopher Hitchens was asked, “Do you have willpower? Do you have free will?” His answer was, “Yes, I have free will. I have no choice.” [Laughs.] And this idea that we’re wired to have free will, this ego, all the things we’re trying to escape, ego and laziness—that’s it doing us! You’ve got it, man—you’ve got this ego! Don’t try to get rid of it, necessarily. Get intimate with it—get to know it well. I love that word, “dig.” Maybe just dig it, you know? Give into it and say, Oh, look what’s happening to me. Interesting.

In the nineteen-seventies, when you were making these songs, you were also spending a lot of time with the writer and scientist John Lilly, hanging out in sensory-deprivation tanks. Is that a habit you’ve kept up with?

I haven’t. I loved the experience, though.

I did it once.

What’d you think?

Well, it’s like what you were saying earlier—I found it uncomfortable, and then I had to force myself to tolerate my own discomfort rather than doing what I wanted to do, which was kick the door open.

John Lilly used to shoot acid and get into that thing for twenty-four hours.

Good lord!

Yeah, exactly. [Laughs.] First thing when I got in, he’d say, “Close the lid. Now I want you to get in and out three times.” I’d say, “Why’s that?” “Well, that’s to program the computer in your brain that you can get out.” But, like you say, when I first got in there—it’s everything to take all of your senses. What is consciousness when you don’t have any input? That’s kind of what you’re trying to get to. You’re in this water, and my mind goes, John Lilly, what kind of guy is he? He’s in that weird jumpsuit. . . . Did he have breasts? What’s in this water? Wait a minute, is he experimenting on me? All these thoughts—fear thoughts. And then you’d say—Oh! You notice, oh! That’s not being supplied by anything other than my mind. You sit in there for, you know, three hours or so, and different stuff comes to light. I don’t know if you experienced this, but I remember getting out and the colors were very rich. I realized that the projecting that I was doing inside the isolation tank was still going on. It’s always going on.

I read an interview from you from around this time where it sounded as though you were pretty regularly seeking out fear as an engine of catharsis. If you can confront something that scares you, or put yourself in a situation that’s uncomfortable, you’re going to grow.

Yeah. Something’s gotta pop.

Do you still do that?

On a good day, I do that.

Because that idea also feels central to this music—just getting as far away as possible from, “That sounds bad.” “I don’t know what I’m doing.”

In those jams, it was such a safe space that it was easy. A good environment for surrender.

Man, surrender is a big idea.

Have you heard T Bone’s new album? It’s really good. Very folkish and very simple, stripped-down. What triggered that in my mind is the word “surrender.” He uses that: “Everybody wants peace, but nobody wants to surrender.”

It’s a loaded word, in a way, because we associate surrender with cowardice, with being conquered. Maybe that’s a very American idea—you surrender, you fail. But there’s so much that’s beyond our control.

We’ve lost five homes to natural disasters. Earthquakes, fires, and floods. Earthquakes brought us up here, to Santa Barbara. That Northridge earthquake, in L.A., that was the last night we spent in that house. It was wiped out. And then this last fire, in Malibu, our family beach house burned down. I remember after the earthquake, how quickly you’d see people back at it. We have this built-in denial that’s probably a blessing. Because if we didn’t have it, we wouldn’t even get outta bed, you know? Thinking about what could happen, Oh, my God! So you just deny it. You just go on about your business.

That’s such an incredibly beautiful thing about being human—somehow we’re still so oriented toward hope! You get out of bed every day, you fall in love, you have babies, you do the thing, even while knowing exactly what’s gonna happen to you and everyone you love.

That’s right! That’s right! I wrote a song for the “Emergent Behavior” series: “I’m livin’ like I’m already dead.” Like you say, it’s so quick, you might as well say it’s already happened.

That Carl Sagan thing, the “pale blue dot,” have you ever seen that? It’s so beautiful. The Voyager was so far out into our solar system. And Carl Sagan said, “Let’s turn the camera around and shoot what planet Earth looks like.” And nobody wanted to do that. Finally, he won, he got his way. And this thing, this photograph, is of a pale blue dot. It puts it in perspective in the most beautiful way.

How did drugs change the shape of the Wednesday-night jams?

We were all experimenting with pot, certainly. Acid, coke, quaaludes. Whatever was around. Booze. I remember sitting with Mike Portis and Steve Baim, at Baim’s house, sitting around a lime tree taking a gallon of gin, pouring it into a plastic water bottle, picking the limes off the tree, squishing ’em into the bottle, and chugalugging, the three of us. We chugalugged that thing, and oh, what a terrible adventure we had . . . but it was an adventure. Let’s get fucked up, let’s see what happens. I’m amazed now that we survived some of that scary experimentation.

Did you have a moment where you felt as though you had to choose between a career in acting or a career in music?

My parents loved acting so much. They encouraged all of their kids to go into it, unlike a lot of entertainers. But as a teen-ager who wants to do what their parents want ’em to do? I resisted. Beau, my elder brother, is eight years older. The music coming out of his room was Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Buddy Holly, the Everly Brothers. And then my music, you know, everybody probably thinks their era is the best music, but mine? Beatles? C’mon. Bob Dylan, Stones, Motown. All of this great stuff. The idea of being in a band was so attractive to me. And my father said, “Don’t worry. That’s what’s great about acting. You’re called upon to explore all those interests.” I’m glad I listened to the old man, and I’m also glad that this music kept bubbling up in different forms.

What does songwriting feel like for you?

Have you ever done “The Artist’s Way”? Morning pages? The assignment is to not stop moving your pencil, and then you’re not supposed to read what you wrote until maybe months later. I’ve done the twelve-week course twice, so I’ve got a stack of spiral notebooks. Talk about resistance . . . at first, it’s like a homework assignment. But then you’ve got three pages, and it’s, Oh, let me do just one more page. On a good day, writing a song is kind of like that. You just let it do you. Let it come out. Then it feels like everything is working at once: you’re hearing, you’re seeing, you’re smelling, you’re feeling. It’s pretty rare. And I find that the older I get the less it happens to me. It’s kind of frightening in a way, because it’s that surrender thing you’re talking about. Where’s this leading me? Falling in love is like that: I’m gonna open up to this person. This person is gonna mean this to me.

Love is surely the biggest surrender.

Isn’t it? And it’s what we all want and desire. But then how do you practice feeling it?

Can you?

I don’t know! Acting is all about love in one sense. There are different ways of approaching it. One style is “Please just call me by my character’s name, and I’d rather not engage too much.” I’ve had wonderful experiences working like that. It works well. And the other way—and I tend to work this way more—is to accept that we don’t have much time to get down as deep as we need to go for this. So let’s work together as a team on how we do that. How do we relax each other? And get intimate without fucking. You don’t wanna fuck . . .

Or maybe you do. But you shouldn’t!

It doesn’t work! It’s a bad thing! But you need to get intimate and get to know each other. It could be a guy, too. Like, with John Lithgow, in “The Old Man,” we became fast friends very quickly, because we both act with the same approach. We get to know the other person so we can relax, feel comfortable. Now that I know you, I know I can push your buttons a little bit. You get into it. It happens with women. With Amy Brenneman, it was that same thing. It’s amazing how accessible love is. We were talking about practicing love—with a movie, that’s kind of the object of the game. Because like you said, there’s a commonality: we’re all gonna die—we all wanna be loved and to love. There’s a commonality that you can tap into, if you both acknowledge it.

That kind of love—a love rooted in realizing we’re all exactly the same—can feel so easy. On a day when I’m really awake to that notion, to how vulnerable and extraordinary we are, I love everybody!

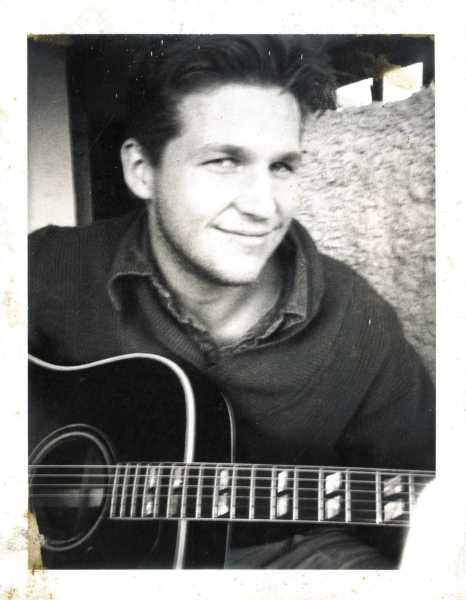

That’s what makes it frightening! Because you say, I could love this person! Am I going to? With me, I resist it. I resisted getting married. Should I tell the story? I fell in love with my wife in Montana, when I was doing a movie called “Rancho Deluxe.” I’m doing a scene in a hot tub, at a dude ranch that used to be a hospital a hundred years ago. And I’m in this hot tub with Harry Dean Stanton and Sam Waterston and Richard Bright. We’re sitting there doing our scene, and I see this girl—I cannot take my eyes off her. Gorgeous girl. She’s got two black eyes and a broken nose. The juxtaposition of that, the trauma and the beauty . . . I said, “I’m gonna ask this girl out.” I said, “Hi, would you like to go out with me?” She said, “Mmm, no.” I said, “No?” She goes, “No.” She says, “It’s a small town. Maybe I’ll see you around.” I said, “Oh, O.K.”

And now we cut to thirty years later and we’re married, and I’m at my desk going through some mail, and I get a letter from the makeup man on “Rancho Deluxe.” He said, “I was going through my files, and I found this photograph that I thought you might like. It’s you asking a local girl out.” So I have a photograph of the first word that my wife ever uttered to me, which was “No.” Isn’t that wild? Whenever I think, Is she the one? I think of moments like this. There are quite a few of them. When I fell, it was just boing! I was just done. Love at first sight. But then we lived together for three years. We got married in seventy-seven, but I resisted it. My mother says that I have something called abulia. Isn’t that a good word? “Abulia”?

What does it mean?

It means not being able to make up your mind. It’s a mental illness called abulia. [Laughs.] I could not make up my mind. I thought, if death is the end of the story, the end of the book, then marriage is a giant step in that direction.

Oof.

This is the woman. There’s no more fuckin’ around. This is it. A fear of death is the same as a fear of marriage. So I resist, and she says, “I understand your abulia. I understand you’re very fond of me, as I am of you. But my biological clock is going. I want to get a real relationship and have kids, so I’m gonna go back up to Montana.” And I said, “I cannot let this happen.” It’s like I had sand in my hand, and a very small diamond, and if I let it slip through . . . for the rest of my life I’d be thinking, That was the one! What the fuck! So I knew that was the day. I got down on my knees and I said, “Will you marry me?” And she said, “Yes. When?” And I said, “Well, what is today? Thursday?” She said, “Yeah. How about Sunday?” So we called our friends, we just had ’em over to the house. Now cut to maybe a week later and we’re in Maui at the Seven Sacred Pools. Gorgeous. Talk about a miracle. All I’m doing is just smelling the rotting mango, and I’m a pouty motherfucker. [Groans.] Sue’s saying, “Let’s annul this.” I’m saying, “No, no . . .” And she put up with that shit for about three years until I finally got with the program. Thank God she didn’t kick me to the curb! You know?

What changed after three years?

I finally got it. I said, “God, you are such a lucky . . .” It’s that same thing, waiting for this miracle, and it’s right in front of you, man! You are so lucky! You think, Oh, is she hoodwinking me? Nah, man, you’re a lucky son of a bitch.

You are. But I suppose I know what you’re saying, about marriage and death. Because when you think about love as the most reliable miracle, the most godlike feeling we can actually tap into—well, it’s a big door to close.

Yeah, I fuckin know! But what happens is . . . life wants to fuck with you! Life! Will! Fuuuuuck! With! Youuuuuu! It will take you. It will take you!

But you did it. Forty-eight years! That’s amazing. That’s rare.

We’ve known each other for half a century. And the rough patches, your death experiences, that’s actually the treasure. That’s the gold. You’ve gone through the thing together. Do you wanna see the picture of when I met Sue? [Bridges digs a photograph from his wallet.]

Oh, my God.

The moment! “You wanna go out with me?” “No.” Look, you can see, I’m fucking done.

Look at your face! You’re so fucked!

Isn’t that something? ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com