Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

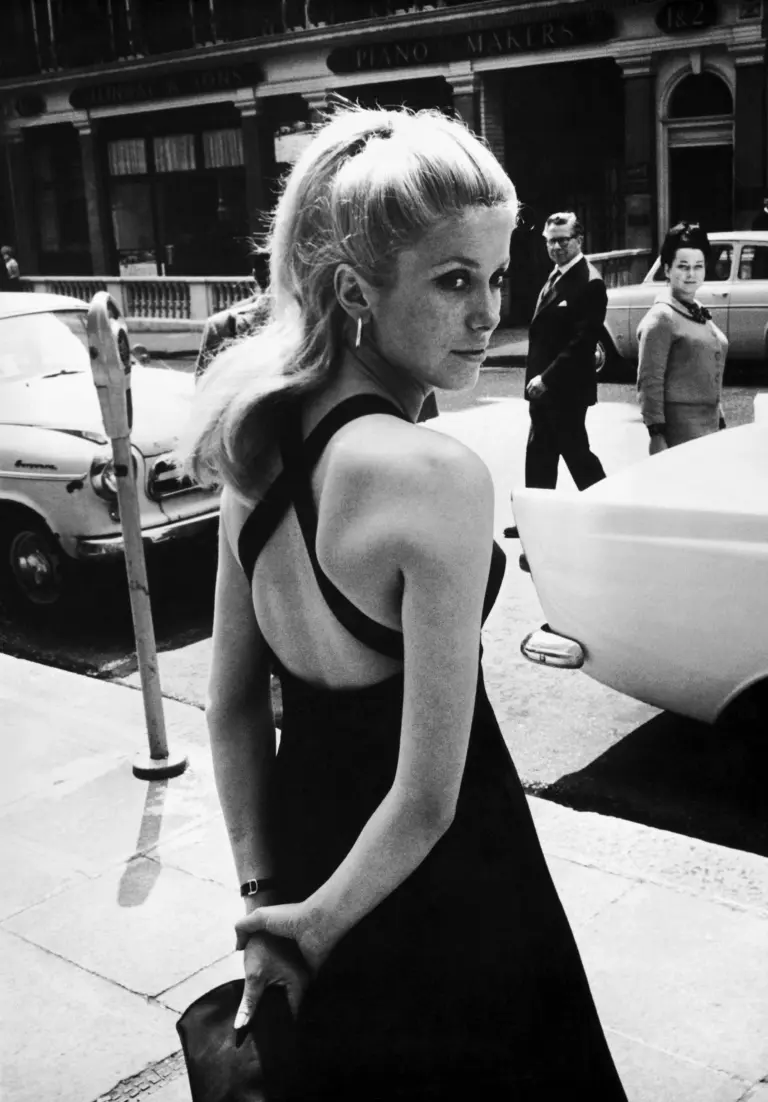

Jamie Lee Curtis is Hollywood royalty: her parents were Janet Leigh, the star of Alfred Hitchcock’s “Psycho,” and Tony Curtis, the matinée idol from “Sweet Smell of Success.” She belongs to a specific class of actors who use their easy entrée into the world of celebrity as an opportunity for scorched-earth storytelling from behind the curtain—think Anjelica Huston in her memoir, “Watch Me,” or Carrie Fisher in her autobiographical novel “Postcards from the Edge.” Curtis was as frank and outspoken as ever when she spoke with me recently, to promote her new film, the murder mystery “Knives Out,” from the writer and director Rian Johnson. Curtis plays Linda Drysdale, the wealthy daughter of a slain mystery novelist who gathers with her family in her father’s Gothic manse to try to get to the bottom of his demise. Was it suicide? Was it foul play? Was it Jamie Lee Curtis? I’ll never tell. And it turns out Curtis is also good at keeping secrets: she’s currently working on a project about her parents, but won’t yet disclose any details. She did speak with me about opiate addiction, Hollywood beauty standards, her foray into writing books for children, and her long-ago stint as Bette Davis’s condo-board president, among other things. Our conversation has been condensed and edited.

Do you have any history with whodunnit movies?

No! I am the anti-mystery girl. I don’t like horror films.

Wait. How can that be?

I scare easily—I have since I was a child. Loud noises scare me, suspense music scares me. There’s not a movie that my friends haven’t all said, “Oh, I’m going to go see this movie,” and then they look at me and they say, “But you can’t go.” Including “Parasite,” which all of my friends were telling me is this fantastic movie.

There’s a whole trend of people who read the Wikipedia entry for a scary movie before they see it—they spoil it for themselves.

Well, I’m going to tell you a secret. I was making “My Girl” in Florida, and the makeup man had done “Silence of the Lambs” and it was out in theatres. He wrote me a crib sheet, which I took with me into the theatre with a little flashlight, and I sat in the back row by myself. It read, “When Jodie goes to the storage locker, close your eyes and ears and wait for the second scream,” and I would cover my ears, close my eyes, curl up in a little ball, and sing “Au Clair de la Lune” in my head.

That might be a million-dollar idea for an app—like, you start it at the beginning of a movie and then it will tell you, “Look away now.”

There’s an entire industry built on the fact that people like to be frightened, and I understand it. They pay money—good, after-tax money—to go and buy expensive bad popcorn and sugar drinks just to sit there to be tortured by a filmmaker.

I want to talk a little bit about your costuming in “Knives Out,” because it was beyond. You spend most of the movie in tailored, jewel-toned pantsuits.

I called Jenny Eagan, the costume designer, and I sent her a picture of my friend Patti Röckenwagner. She was wearing this head-to-toe raspberry-sorbet blouse and trouser, and I said, “That’s Linda Drysdale.” She’s a Realtor. She has to dress every day. She’s from money. She’s earned her own money. They live in a poshy apartment in Boston. So elegant, swellegant, with some edge. The pop of color, which I thought would be sensational, knowing that it was a Gothic house.

Rian Johnson put so many references to old mystery films in this movie. Are you interested in Hollywood history?

I lived a little of it. I gave a book to Rian and his wife, Karina, when I first was signed on to “Knives Out,” as a way to sort of say hi. It’s a book that I buy off of eBay all the time, by a man named John Kobal, called “People Will Talk.” Gloria Swanson, Mae West—they’re long interviews, and they go into weird places.

I miss those talk shows where it’s Bette Davis in the nineteen-sixties—

Bette Davis! So, I lived in a building in Los Angeles called the Colonial House, and it was referred to as the Dakota West. Bette Davis lived in the building, along with other filmmakers. At twenty-seven, I became the president of the board. Nobody wanted the job, and I was, like, “I’ll do it.” I’m very organized.

And so, two things. One, Miss Davis would call me in July and August, saying, “I want the heat.” I’d be, like, “I’m so sorry, Miss Davis, it’s not possible, because it’s July, and it’s a hundred and five degrees, and we’re all dying, and I can’t turn on the boilers.” She goes, “I want the heat.” She would lay by the pool in a big black hat and a black maillot bathing suit with high heels, black sunglasses.

Then I was in a TV movie with her, set in Valdosta, Georgia. I played her spunky niece, and she was the Southern matriarch of a family where her brother died and left his estate, his plantation, to his African-American housekeeper. She had a sister in the show, played by Penny Fuller. It was called “As Summers Die.” The dénouement was when Bette Davis was going to testify, and we’re in one of those old Southern courtrooms with the mahogany, and it’s in the nineteen-fifties, and she’s in one of those Victorian wheelchairs. We’re coming in from the back of the courtroom. You can imagine: big, wide shot, full courtroom, people fanning, hot summer day. Halfway down the aisle, Miss Davis reaches up and grabs my hand, which is pushing the wheelchair, and says, “Take me back.” The camera people are going, “What are you doing?” Because we stopped. And I turned her around. I’m looking at everybody, like, “What? I don’t know.” I took her into her little dressing room. The director, the producers, everybody’s running in, like, “What did you do?” I was, like, “I didn’t do anything!” So they go in there for twenty minutes. Finally, the director walks out. He walks up to the front row, where Penny Fuller was sitting, and he whispers in her ear, and Penny Fuller says, “Oh, give me a break. Are you kidding me?” And there’s a flurry of people, and the wardrobe woman comes in with a selection of hats. Penny Fuller had to take off her hat because it was red. Miss Davis felt that it would draw attention away from the fact that it was Bette Davis’s scene.

Your family comes from New York?

Oh, yes—Tony [Curtis]. He grew up in the streets of Manhattan. He was a Jewish boy, and he lived in the Jewish neighborhood. He said in order to go uptown you would start running at full speed because, by the time you crossed into the Italian neighborhood, the Irish neighborhood, the Polish neighborhood, you had to be running, because you’d get the shit beaten out of you if they caught you. That told me so much about the hardship of his life. And my mother’s life, in Merced, California—just both of them very poor, economically insecure.

It’s important for me, given that I’m this bougie princess from Los Angeles—even if I claim I worked hard, I’ve never really worked hard a day in my life. I wrote a short story once that was semi-autobiographical, which I’ll never publish, a novella actually—the child in the story was raised in New York with famous parents. The father in that story wrote an autobiography, titled “Access of Kings.” It was that idea that, when you’re famous, you get this incredible access, you get opportunities to see things that other people don’t get to see, you get ease of access everywhere you go. All of that is a great, lovely benefit to the part that you give up, which is your privacy. So it’s a balance.

Let’s talk about your beginnings as an actor. Did you resist it at any point? I know you had a year of college, then started acting and never went back.

You have to remember, I had gray teeth, because my mother took tetracycline when she was pregnant with me. My teeth were gray. I was not pretty. I was cute. I had a lot of personality. My lack of any school success I made up for in personality. I was a jokester from a very young age. And I was surrounded by a lot of people in show business. I never thought I’d be an actor, ever, ever, ever, ever. I was going to be a police officer, because I thought I would be good and you didn’t need a lot of schooling for it. I went to a college [the University of the Pacific, in Stockton, California] where my mother was the most famous person to have ever graduated. It was the only school that took me with my D average plus 840 combined SAT.

Why were you so bad at school?

Today I’d be diagnosed with some learning disability or learning difference. I am a great reader, but I don’t retain that much. I moved to three high schools in four years.

Were you popular?

I was a cheerleader. I had no discernible skills. I was popular because I was fun. I was insecure. We could do an entire twelve-hour miniseries on high school. It was a nightmare.

And was the one year of college also a nightmare?

What happened is I went to college and became a little sister at a frat. At Christmastime, I came home. A friend of mine from Beverly Hills had a tennis court behind her house. A man named Chuck Bender [was there], and he said, “I’m managing actresses, and they’re looking for Nancy Drew at Universal; you should go up for it.” And I went up and auditioned, and didn’t get the job. But, he said, “You should stick around. You could get work.” I called my college and I said, “Can I get credit for drama if I go to acting class for a month?” And they said yes. So, during that month, I ended up auditioning a hundred times for things and not getting much. Then I auditioned for a program which is no longer in existence, which was a contract system.

When I read about that, I thought, God, she must have been the last person put under contract at Universal.

I was virtually one of the last people. And they had probably twenty men and twenty women, they paid them weekly. And then they started filtering them into TV shows with the goal that, at one point, you would land a big job, but they would be paying you two hundred dollars a week, and they wouldn’t have to pay you ten thousand dollars a week.

You took acting classes. Did you have a sense of the craft that goes all the way back to the beginning? Or is it something that’s ad hoc, that has developed over the years?

Totally just what I’ve picked up. I have learned that, whatever it is, there is no formula for anyone—there is no one way to do it. There have been times where I have felt less than, because other people seemed more articulate.

I did a wonderful movie with John Boorman called “The Tailor of Panama,” from a John le Carré novel, with Pierce Brosnan, myself, and Geoffrey Rush. Geoffrey and John are both intellectuals. They’re both deeply into character. I cut my teeth in horror movies, where you don’t have any time—you just show up as the person, and you do the work, and you get a take or two, and then they have to move on. I remember a day where Pierce and I were sitting in this room with John and Geoffrey, where they were deep-diving into things, and, at one point, Pierce looked at me and I looked at him, because Pierce cut his teeth on “Remington Steele.” [Afterward] we were in an elevator, and I looked at him and said, “Pierce, I feel like such a bad actor, because I’m not deep-diving like that.” And he goes, “Yeah, me, too.” But, the truth is, there is no depth.

How did “Halloween” come about?

I'd been on a TV series called “Operation Petticoat,” a remake of the Tony Curtis–Cary Grant comedy set on a pink submarine in World War II, where five Army nurses get picked up on an island. Hilarity ensues when you have five Army nurses on a Navy submarine in the middle of war.

So it’s like a pajama romp, but a war movie?

I was cast in the part that was opposite the part that my father had played in the movie. It’s almost incest, but not. It’s generational incest. While we were shooting the movie, it got picked up as a TV series. All of a sudden I became a regular on a half-hour comedy. Every week I would have one line. If I had two, that was a miracle.

Do you remember any of the lines?

No. The show did not do well. And I was fired, along with eleven of the thirteen actors. I was devastated. I thought my life was over. I thought my career was over. I thought I would lose my contract. And two weeks later the audition for “Halloween” came up. . . . It’s one of those good stories for people who’ve just been let go from their job.

Did you have a feeling when making “Halloween” that it was the thing it would become?

Nothing. All I can tell you is that my [character’s] name was on every page of the script, and that it was thrilling to actually create something as a character.

Do you know why you got the job?

I auditioned many, many, many times. And then it was between me and one other woman, whose name I know but I will never say publicly. I’m sure the fact that I was Janet Leigh and Tony Curtis’s daughter, and that my mother had been in “Psycho”—if you’re going to choose between this one and this one, choose the one whose mother was in “Psycho,” because it will get some press for you. I’m never going to pretend that I just got that on my own, like I’m just a little girl from nowhere getting it. Clearly, I had a leg up.

Were you hesitant to do a “Halloween” update, forty years later?

No, because when David Gordon Green and Danny McBride sent me the script, I saw exactly that they were honoring the fact that, when something that traumatic happens to you when you’re seventeen, eighteen years old, it carries with it a tremendous effect.

Was it important to you that they also explore addiction?

Well, it is a by-product of trauma, by the way. Painkillers, alcohol—it is the balm that heals people when they are so traumatized. There’s no accident that people coming back from war fall prey to drugs and alcohol as the relief from the trauma. It’s natural. Hurt people hurt people, hurt people seek relief. It was clearly going to play a part in that movie.

It’s been twenty years for you in recovery—

I am twenty-one years sober coming up in February.

Has that been fairly unexpected for you, to be a public representative for treatment and recovery?

I’m a public representative for a private issue. I was so terrified when I got sober from a ten-year run on Vicodin and alcohol. I was terrified about being outed. I was terrified of the tabloids. I felt like that weakness was going to be exposed and then exploited. I would feel so embarrassed by that exposure of a secret, of a flaw of human frailty.

And then I was doing an interview for Redbook about a book for children that I had written. My teen-age daughter was sitting with me. We were at the table with the author, a really good journalist. I was talking about how great my life was, how happy I was, and how much better, I kept saying the word “better.” At one point, she said, “Well, what do you attribute to that?” Not fishing, not twirling her mustache. I looked out the window, and I turned back and said, “I think it’s because I’ve been sober for over two years.” I could see that she was, like, “Whoa, O.K., I now have a whole new angle on this story.” I knew I was giving that to her. I felt like it was important to talk about opiates.

The culture is catching up to you.

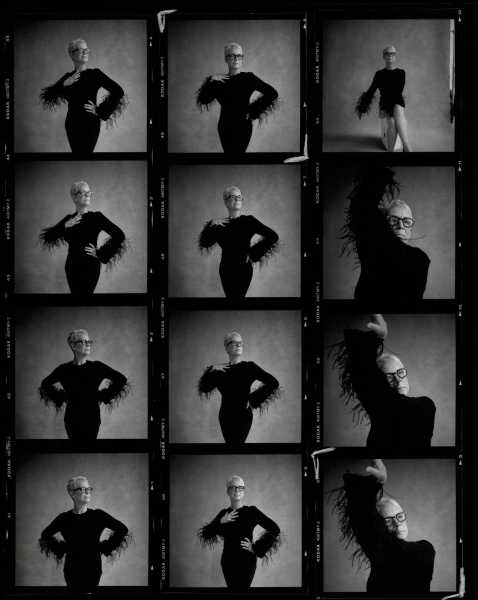

I recently did a cover story for Variety. They said, “We are going to do an annual recovery issue, and we’d like you to be the cover story for our first issue.” I said, “Absolutely.” When I got sober, twenty years ago, there was a magazine article in Esquire, written by Tom Chiarella, where he outed himself to his editor and family that he was a Vicodin addict. It was in January of 1999, and I got sober February 3, 1999, because I read that article. For the first time, I understood that I wasn’t alone. He talked about where [the pills] were hidden in his house, and I thought, Oh, I hide mine in my cowboy boot, too. So I figured if I did that in Variety, maybe somebody who is at home, secretly dealing with an opiate addiction—maybe they would seek help.

Over the years, the stories you’ve been telling about your past with opiates and addiction have dovetailed with your thoughts on the exacting beauty standards in Hollywood.

I knew I was going to do the cover of More. I said, here’s the deal: I will take a picture in my underwear, with no makeup, no hair, no fancy lights, with my body the way it is, if you promise you will print that, head to toe, on a separate page, and then print the picture of me fully glammed-out on the next page. That was my deal with them, in order to talk about the reality of self-esteem, and about the fact that I had undergone plastic surgery, which is where I first found Vicodin. I underwent an eye job when I was thirty-five years old because, one day, I was on the movie “Perfect,” and Gordon Willis, the great cameraman, looked at me and said, “Yeah, I’m not shooting her today.” I was puffy that day, for whatever reason. I was mortified. Right after that movie I went and had an eye job. That’s when I found Vicodin, and the cycle of addiction began with that.

I want to talk about your career as a children’s-book author. You’re such a lovely writer of children’s books. And you’ve done so many!

All by accident. The last thing I ever thought I’d do, besides being an actor, would be to be a writer, because I didn’t feel I had the acumen.

Did someone approach you?

No, no. My four-year-old daughter, Annie, was in her room. I was in my office down the hall. She marched into my room and stomped her feet and put her hands on her hips and looked at me and went, “When I was little I wore a diaper, but now I use a big-girl potty.” I thought, Oh, she was talking about the good old days. She was talking about her past. All of a sudden, I understood she had a past. I wrote down on a yellow pad, “When I Was Little: A Four-Year-Old’s Memoir of Her Youth.” I wrote a list of things that she used to not be able to do; now she could. And at the end of it I wrote three things, and I started to cry: “When I was little, I didn’t know what a family was. When I was little, I didn’t know what dreams were. When I was little, I didn’t know who I was. But now I do.” I realized, Oh, this is a book for children.

I sent it to my mother-in-law’s best friend, a literary agent in New York City named Phyllis Wender. I remember sending it when faxes were new. She sold it that day, to HarperCollins, which was called Harper & Row at the time.

How did you come up with the idea for your last one, “Me, Myselfie & I”?

It was originally titled “Mommy Got a Selfie Stick.” When I was selling it, they thought it meant a vibrator! So we changed it. But it was a cautionary tale about this obsession with ourselves and narcissism and how we are teaching children that it’s all about them and what they look like. And the constant, constant need of self-photography. Like, what are we doing? This is insane.

You’ve been married to Christopher Guest for decades now.

Well, thirty-five [years] and about a month.

How did you meet?

It’s a good story. It was 1984. I was just cast in the movie “Perfect.” I was in L.A. I was doing a lot of aerobics. My friend Debra Hill, who wrote “Halloween,” was sitting on my couch in my apartment in West Hollywood, where I lived with Bette Davis.

It’s all coming full circle.

We opened Rolling Stone, the issue with Cyndi Lauper on the cover. There’s a picture of three guys in plaid shirts, sleeves rolled up, regular-looking dudes. I said to Debra, “Oh, I’m going to marry that guy.” She said, “I tried to put him in a movie. His name is Chris Guest.” I turned the page, and it was them as their Spinal Tap characters. She said, “He’s with your agency.” The next day, I called the agency. They said, “I know all about it. Chris Guest.”

Debra had called already?

I said, “Oh, I’m mortified. Here’s my number. I think he’s cute. I’m single.” Done. Never heard from him! Ever. He didn’t call me. Time went on.

Melanie Griffith and Steven Bauer were living in West Hollywood at the time—we had become friends on a TV movie. We went to Hugo’s restaurant, in West Hollywood. We sat down at a table, and when I looked up, two tables away was Christopher, facing me. He raised his hand to gesture, like, Hi, you called me. And I gestured silently, with my hand, Hi, I called you.

Five minutes later, Chris got up to leave, shrugged his shoulders, and put his hand up again to say goodbye, and I shrugged my shoulders and waved goodbye—didn’t say a word to each other. He laughed. And he called me the next day. That was June 28th. We went out July 2nd for our first date, and he was leaving to go do “Saturday Night Live” for one year on August 8th. He did try to get out of his contract. I didn’t know that then, but he did. They did not let him out of his contract. He went to New York. I was in L.A., and we went back and forth every weekend. We got engaged in September, and we got married in December of that year.

Did you ever have any inclination to do his style of comedy?

I can’t make up anything. The only line I’ve ever made up in my life ended up in “Freaky Friday,” where I told Lindsay [Lohan] to make good choices. I could never improvise comedically. I’m jaw-dropped by what they are able to do. So, no, I don’t think we’ll ever work together.

Are there any roles that you’ve done that you think are unsung, that no one asks you about?

Please. You know what? I get so much effing attention, which is just obscene, really. I’ve been doing this for a long, long time, and I’ve been successful at it since I was nineteen. There’s not a day I don’t walk down the street and somebody goes, “Hey, I love you. You’re fantastic.” And I appreciate it. I get it. It’s been my gig. I don’t need any more attention.

Sourse: newyorker.com