Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

What does it mean—what would it mean—to “decolonize the city”? As that phrase has become common among architects, artists, and activists in recent years, it has operated more like a slogan, a blunt exhortation, than a plan of action. A growing critique of the imperial and colonial legacies of Western powers, accelerating with the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, has cracked open the question of how European nations and the United States built the wealth that funded some of their greatest wonders of architecture, art, and urban form, and revealed the violence that supported it. Protesters took this critique into the streets by toppling, decapitating, or defacing dozens of statues honoring colonial and pro-slavery figures; cities, proactively, took down others. Scores of institutions with contested names chose new ones: Brooklyn’s General Lee Avenue was renamed for the Black Army officer John Warren, killed in Vietnam at twenty-two; Junipero Serra High School, in San Diego, is now Canyon Hills High.

But what comes next? How will cities grapple with the more difficult question of what to do with fraught landmarks that are more immovable than those statues—museums, train stations, and private houses, say—or whose connections to racism or slavery, while significant, are tougher to precisely trace? Perhaps, before we can get a clearer sense of what decolonizing the city will look like, we need to better understand how, and by what architectural means, it was colonized in the first place.

One of the most compelling explorations I’ve seen of where decolonization efforts might turn next was on view this summer at an architecture museum in Brussels called CIVA, for Centre International pour la Ville et l’Architecture. “Style Congo: Heritage & Heresy,” curated by Sammy Baloji, Silvia Franceschini, Nikolaus Hirsch, and Estelle Lecaille, was able to say something meaningful about the sprawling task of decolonization by focussing on the architectural by-products of a single imperial campaign: Belgium’s violent and lucrative occupation and eventual colonization of Congo, under King Leopold II.

The style in “Style Congo” is Art Nouveau. Once understood primarily as an inventive but transitional movement that allowed the last embers of Victorian revivalism to burn themselves out, clearing the way for the streamlined abstraction of modernism, Art Nouveau found particularly vital expression in Belgium, in architecture by Victor Horta, Paul Hankar, and Henry van de Velde, and in art works by Philippe Wolfers and others. Crucially, Art Nouveau also emerged in Belgium around the same time that Leopold, in 1885, became the ruler of the new Congo Free State, which he operated as his personal fiefdom, pulling out its stores of rubber and ivory, until Congo became an official Belgian colony in 1908. What is now the Democratic Republic of the Congo gained independence in 1960, and was known as Zaire from 1971 to 1997.

Historians have long described Art Nouveau, with its fluid, snaking ornament, as “le style coup de fouet”: the whiplash style. But it’s only in recent years that scholars, looking more deeply into the connections between Art Nouveau and imperialism, have directly linked either phrase to the vast human toll Belgium exacted in Africa. The writer Adam Hochschild, whose 1998 book “King Leopold’s Ghost” first exposed a wide reading public to the history of Belgian imperialism in Africa, estimates that “toll of Holocaust dimensions” at ten million lives; others use somewhat lower, if still staggering, figures, which can range from five million to eight million Congolese deaths between 1885 and 1908.

Belgian Art Nouveau, as the U.C.L.A. art historian Debora Silverman put it in an incisive lecture at CIVA, was “created from raw materials from the Congo and inspired by Congo motifs.” Even more striking, she has suggested that Art Nouveau was the specific means by which the violence carried out in Leopold’s name in Congo snapped back and found its way, in abstracted or semi-abstracted form, into Belgian culture—allowing that small and geographically squeezed nation, its nineteenth-century ambitions largely thwarted at home, to indulge, through its art and architecture, in “a fantasy of domination.” Silverman sees not just natural and animal forms “embodied” in Art Nouveau’s curves; she also sees the leather whips that Belgian forces used to bloody Congolese laborers.

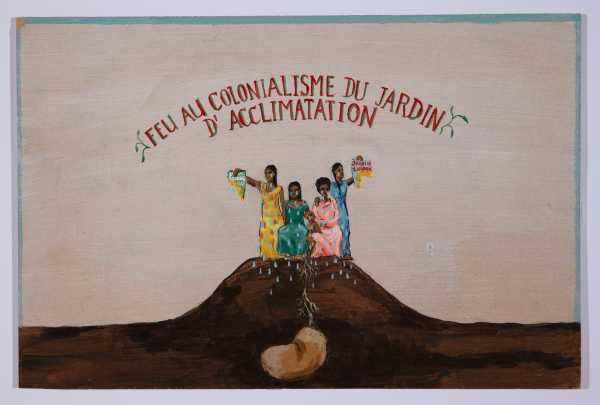

The Rebellion of the Roots (France).Art work by Daniele Ortiz / Kadist Collection Paris / Courtesy CIVA

The first thing visitors to “Style Congo” encountered was “Monument,” a 2005 work by the German artist Peggy Buth, that takes the form of an asymmetrical and empty black plinth. Though the art work predates the murder of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement, it succeeded here in pointing the way forward: Its placement in the museum’s lobby suggested that “Style Congo” took the post-B.L.M. world, with its toppled statues and vacated pedestals, as a given—an uncertain starting point.

Inside the exhibition galleries, the focus was on the way that Art Nouveau and representations of Congo overlapped and fed one another in a range of international expos and other colonial exhibitions between 1885 and 1958. (The expos essentially announced that Congo was open for business, so long as investors could strike the right deal with Leopold and his successors.) The centerpiece was a large installation by the Brussels collective Traumnovelle, a group described by its founders, the architects Léone Drapeaud, Manuel León Fanjul, and Johnny Leya, as a “militant faction.” On wire-metal walls that resemble screens used for archival shelving, Traumnovelle had hung scores of architectural drawings, photographs, brochures, newspaper clippings, and other materials reflecting the influence of Congo on Belgian architecture, from the founding of the Congo Free State through the Brussels World’s Fair of 1958.

Along the perimeter of the CIVA galleries and in adjoining spaces, as if looking over the archival materials in the center in patient judgment, were works by another half-dozen architects, scholars, and contemporary artists, some newly commissioned by the curators. One was a series of portraits by the photographer Chrystel Mukeba of Congolese Belgians posing inside Art Nouveau landmarks, including the elaborately ornamented house that Victor Horta designed in the eighteen-nineties for Edmond van Eetvelde, who administered the Congo Free State for Leopold. Mukeba told a reporter for the Belgian magazine The Parliament that half of the building owners she approached never got back to her or turned her down: “A fashion shoot or something like that, there’s no issue,” she said. “But as soon as you start to want to have people of African descent pose,” she added, “then it becomes a lot more complicated.”

This is hardly a surprise. By many accounts, Belgium has been slow to grapple with its Congolese legacy. Last year, a commission established in 2020 by the Belgian parliament deadlocked on the basic question of whether the country should issue a formal apology for its colonial past, to say nothing of larger issues like reparations. But the dam had begun to break, or at least crack, by the late nineteen-nineties. “King Leopold’s Ghost,” which became a worldwide best-seller, appeared in 1998, followed the next year by Ludo De Witte’s “The Assassination of Lumumba,” which examined the Belgian government’s role, together with the C.I.A. and the Belgian mining company Union Minière du Haut-Katanga, in the removal and assassination of Patrice Lumumba, the independent Congo’s first Prime Minister, by his political rivals. After Lumumba’s body was chopped into pieces, it was dissolved in a barrel of sulfuric acid supplied, according to De Witte, by Union Minière, which also provided the copper and tin for a statue of Leopold that still stands next to the royal palace in Brussels.

In 2005, the Royal Museum for Central Africa, in Tervuren, formerly the Royal Museum of the Belgian Congo, mounted an exhibition called “La Mémoire du Congo: Le Temps Colonial.” Hochschild found the show “evasive”; Belgium still appeared to him to be struggling to wake from the century-long national amnesia that he has dubbed “the great forgetting.” Silverman similarly criticized the exhibition for a “tepid and reluctant revisionism.” She credits a decorative-arts survey the same year at a different institution, the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels, with making the depths of the connection between Art Nouveau and the Congo Free State apparent. The show included an art work from 1897 by Philippe Wolfers called “Civilization and Barbarism.” Made of Congolese ivory provided to the artist by Leopold, it features two figures in battle: a swan (to represent Belgium and the “civilization” of the title) against a dragon, standing in for “barbarism.” Silverman told me that seeing this work unmasked “the ideology propelling the project” of the Congo Free State and suggested just how deeply it was embedded within the most significant Belgian art works of the period. This same ideology helped give rise to the story Belgians sometimes told themselves about the nation’s exploitation of Congo: that the occupation was driven in significant part by a desire to free or protect Africans from slavery.

Silverman told me that another part of her epiphany had to do with the U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq, which reminded her in certain ways of Belgium’s campaigns in the Congo Free State. In both cases, “You had violence at a distance, and empire at a distance. The parallels there were very powerful. Violence that you can’t see.” These insights seemed to demand a new look at Art Nouveau, one that she and a growing number of scholars have dedicated the intervening years to exploring.

Leonie Ngoie, Hôtel van Eetvelde.Photograph by Chrystel Mukeba / Courtesy CIVA

Which brings us to the current moment. In a recent article (co-written with the editor Nick Axel), the “Style Congo” curators argue, “the protest, defacing, and at times removal of monuments in public space around the world has been a meaningful step. . . . But what about the buildings that colonialism built? What about the aesthetic experiences they are designed to instill—of beauty, of wonder, of fear, of pride? What about the language we have to understand the past and present, and to imagine the future? There is still much work to be done.”

Some of that work, surely, includes a newfound focus on detail and nuance. The Belgian experience, for instance, doesn’t fit at all neatly into narratives suggested by the phrase “settler colonialism,” which is sometimes used in academia as a catchall term, smoothing over important historical and political distinctions. What Belgium practiced in Africa in the Congo Free State period was not colonialism but imperialism—building an empire of extraction. For Leopold, who never set foot in Congo himself, an arms-length approach remained highly lucrative: estimates of his personal profit from Congo, in today’s dollars, exceed a billion dollars.

This focus on clarity, of task and historical precedent, may be helpful when it comes to answering the tricky question of what to do with buildings whose origins, architectural and otherwise, are inextricable from imperial or colonial violence. In Belgium’s case, this will apply primarily to the fate of landmarks and other public works that were commissioned by Leopold and paid for directly with wealth earned via the Congo Free State. The scale and ambition of such projects marked a major shift for Belgium and its royal family, which before 1885 had been highly constrained in power and reach. These landmarks, which earned Leopold the nickname the Builder King, include, among many other examples, Antwerp’s central railway station; the ceremonial avenue linking Brussels and Tervuren that Leopold built ahead of the Brussels International Exhibition in 1897; Brussels’s massive triumphal arch, modelled on Rome’s Arch of Constantine but far larger; and the Royal Galleries in the seaside resort town of Ostend.

The station in Antwerp, designed by Louis Delacenserie in an eclectic brand of style, including Art Nouveau, and built between 1899 and 1905, is a representative case. It would be tough to find many Belgians who think it should be fundamentally altered, to say nothing of demolished, as it remains in operation and ranks as one of Antwerp’s most recognizable works of architecture. It became a protected landmark in 1975. Yet it is nothing less than an architectural portrait of Belgium’s imperial king, whose treasury was stuffed with wealth earned through violence and extraction in Congo.

In a very direct sense, what would be the appropriate decolonizing response to a building like that? Should signage be added explaining the connection between its architectural grandeur and Belgium’s actions in Congo? Should something more dramatic be considered? What form might that take, and who would be responsible for approving it? Belgium’s infamously fragmented and fractious political system, which helped sink the ambitions of the parliamentary commission, seems guaranteed to make this process complicated.

Brussels has declared 2023 “the Year of Art Nouveau.” In October, the city’s Center for Fine Arts, known as Bozar, will open “Victor Horta and the Grammar of Art Nouveau,” which in exploring links between the architect’s work and the Congo Free State will mark a significant step forward for the ninety-five-year-old museum, following the example set by the younger CIVA, which was founded in 2016.

Are phrases like “decolonize the city” too broad or vague—or, as others would have it, too bluntly insistent—to win broad-based popular support? Such complaints strike me as short-sighted: Radically simple demands continue to succeed in slicing through hardened policy and conventional wisdom and opening up space for genuine reform. All the same, such language does need to give way, at a certain point, to the sustained work of more systematically disentangling the urban form of Western cities from their colonial and imperial roots. We need a methodology for this emerging mode of cultural policy: To decide which buildings and other objects that grew from those roots should stay and which should go—and which, beyond that too-simple equation, might be reimagined, redesigned, or otherwise recontextualized in unexpected ways (and how, and by whom).

“Style Congo” is a significant step in this direction. Art Nouveau turns out to be a particularly apt emblem of the insidious power of a world view that over many decades threaded its way into the foundations of twentieth-century Western architecture and urban design. As Silverman put it in her CIVA lecture, Art Nouveau, with its vinelike curves, “laps over and latches on—it’s an aggressive form of nature, and it cleaves, rips, and grips.” Effectively stripping our institutions, and our cities, of the most damaging of these clinging remnants will be the work of several generations. It will require advocacy not only of a patient but of a precise and imaginative kind. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com