Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Tolerance was over. Drag shows, activist-driven science, the spurious multiplication of identities—all of these were to be purged, along with the backstabbing liberals, likely collaborating with foreigners, who’d emasculated the nation by abetting such depravity. Doctors fled as their research was targeted. Censors and vigilantes destroyed the works of “degenerate” artists. In Hitler’s Germany, the scapegoat was Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute for Sexual Science, a center of gay-rights advocacy that also pioneered gender-affirming surgeries. In Trump’s America, it’s an ever-expanding array of teachers, health-care providers, children’s-book authors, and trans athletes. Both crackdowns followed periods of unprecedented visibility for groups previously confined to the shadows. But who were these brand-new people that fascists couldn’t bear to look at?

“The First Homosexuals,” at Wrightwood 659, in Chicago, attempts to answer this question, tracking the emergence of modern ideas about gender and sexuality across more than three hundred art works. It focusses on the period between the eighteen-sixties, when the word “homosexuality” was coined, and the nineteen-thirties, when the Nazis shut down Hirschfeld’s institute and burned his research. The flames have again come so close that the show’s co-curators, Jonathan D. Katz—a founding figure in queer art history—and Johnny Willis, struggled to find a venue in the United States. (Next spring, the exhibition will travel to the Kunstmuseum Basel in Switzerland.) Still, they’ve assembled a monumental survey, which includes everything from Qing-dynasty erotica to Félix Vallotton’s portrait of Gertrude Stein. The show hinges on a word, but its insights are resolutely visual. Art is the world’s greatest archive of sexual difference, Katz argues in the catalogue, preserving subtle shifts that language evades.

“Gertrude Stein,” by Félix Vallotton (1907).Baltimore Museum of Art / Courtesy Wrightwood 659

Take “La Blanchisseuse,” an 1879 drawing by the French artist Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret. Two men wearing top hats stroll, arm in arm, along the Seine in Paris, while a young woman with a bundle of laundry, whom they’ve just passed, invites our sympathy with an exasperated stare. It’s Europe’s first known depiction of an openly gay couple, a status communicated less by their touching than by the laundress’s spurned expression. Her vocation was a common cover for sex work; clearly, she has identified the two men as not only disinterested but ineligible to be her tricks. The look is resigned and beseeching, as though to say, “These gays, they’re trying to murder me.”

To be sure, same-sex relationships have existed since time immemorial. What’s newly visible is the notion that engaging in them might be an exclusive preference and defining quality—in other words, that one could be “born this way.” This theory coalesced in an 1868 exchange of letters, one of which is on view in the exhibition, between two queer Karls—Karl Heinrich Ulrichs, a German lawyer, and Karl Maria Kertbeny, an Austro-Hungarian journalist. It was Kertbeny who coined the words “homosexuality” and “heterosexuality,” which he saw as impulses of which anyone might be capable. Ulrichs, by contrast, believed that men who liked men had female souls, and women who liked women had male ones. More than a century later, their argument is still going: Is it better to fight for universal rights or to advocate for minority recognition? Over time, though, Kertbeny’s word became attached to Ulrich’s understanding of sexuality as innate. The homosexual had arrived.

There’s both power and peril in claiming an identity. “Homosexual” quickly became a pathological diagnosis; at the same time, the word opened a space for collective self-consciousness. A portrait gallery tracks the formation of its visual lexicon, a mélange of dandyism, classicism, androgyny, and theatrical irony that owed much to famous figures in the arts. We see Oscar Wilde, of course, and the Parisian aesthete Robert de Montesquiou, whom Giovanni Boldini shows deep in contemplation of his own elegant cane. Nearby is Montesquiou’s friend Sarah Bernhardt, the legendary bisexual actress—and first woman to play Hamlet on film—who sculpted a “Self-Portrait as a Chimera” (c. 1880) with bat wings. Such was her fame that the feared nocturnal creature, which sleeps in an “inverted” posture, became a queer symbol.

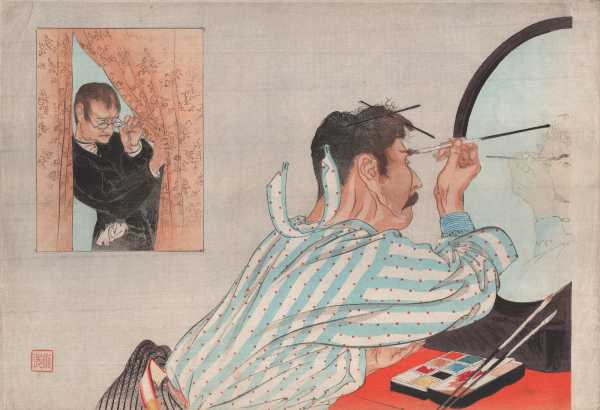

A woodblock print by Tomioka Eisen (c. 1906).Private collection / Courtesy Wrightwood 659

What, besides gay celebrity, made an art work homosexual? Many things, though you can almost see certain stereotypes being metabolized. The show’s first limp wrist belongs to a novelty teapot caricaturing Wilde as a man-woman. Another appears, with knowing affection, in Roberto Montenegro’s portrait of an antiques dealer who wears a polka-dotted bow tie and queenily purses his lips as he proffers a cameo. Finally, in Emilio Baz Viaud’s watercolor “Self-Portrait of the Adolescent Artist” (1935), the gesture has become confident and expressive, the flourish of a keen-eyed young draughtsman with a pencil cocked in his upturned hand.

Later on, partners, families, and homosocial groupings enter the picture. A section on relationships showcases the surprisingly conjugal frankness of lesbian couples around the turn of the twentieth century. “Painter and Child in the Studio” (1893), by the Danish artist Emilie Mundt, depicts a middle-aged woman showing a little girl her brushes and palette, while an elderly man plays piano in the background. The woman turns out to be Mundt’s partner, Marie Luplau; the child, their adoptee; the old man, Luplau’s father; and the painting, one of the very first depictions of a multigenerational queer family in Western art. More explicit is a photo of the British novelist Radclyffe Hall with her lover Una Troubridge. Hall, who privately went by “John,” stands, smoking, in a smoking jacket, while Troubridge, in a dress, reclines on a leopard pelt, like a good wife.

By contrast, the images of gay men are more physically suggestive but romantically ambiguous, probably because, although men’s bodies were less policed than women’s, male homosexuality was more widely criminalized. Groups of bathers, wrestlers, and ironworkers radiate eroticism, but the couples resort to shibboleths, such as the middle finger extended, during a shoulder touch, in Jacques-Émile Blanche’s portrait of himself and his lover. The Spanish painter Gregorio Prieto veiled his libido in de Chirico-influenced Surrealism. In his remarkable “Sueño Marinero” (1932), or “Sailor’s Dream,” a young man in profile looks reverently downward, as though hypnotized, at the crotch of another, who prepares to drop a blanket over the proceedings. It is, quite obviously, the lead-up to a blowjob. And yet the stars and sails in the background, and the silvery, fish-like object that appears in place of a phallus, endow the scene with metaphysical intensity—as though, like Dorothy and Toto, they’re about to be sucked off to a faraway realm.

“Dance to the Berdash,” by George Catlin (1835-37).Smithsonian American Art Museum / Courtesy Wrightwood 659

About those faraway realms: Can we really credit two white Victorians, and their peculiarly German fetish for classification, with the invention of homosexuality? Anticipating this question, the exhibition opens with a global survey of same-sex desire before it had been named. A Japanese woodblock print shows two women preparing to have sex using a strap-on dildo. In a watercolor street scene from post-independence Lima—per the catalogue, the San Francisco of its era—we see a queer brown figure in lace appearing to flirt with a soldier, who wears an enormous cockade in his feathered bicorne. There are nearly as many representations of diversity, including a George Catlin painting of Native men celebrating a two-spirit person, and a portrait of La Chevalière d’Éon, a trans woman who spied for Louis XVI. The ensemble evokes a world full of sexual variety, though far from utopian. One grisly engraving depicts Vasco Núñez de Balboa’s conquistadors and their dogs massacring Native Panamanians for practicing sodomy. It’s a prelude to a later exploration of the colonial influence on sexuality worldwide.

“Homosexuality” was born at the zenith of Western empire, and, much like an empire, it both appropriated from and reshaped the cultures under its sway. Aubrey Beardsley cribbed the oversized phalluses of his erotic drawings from Japanese shunga prints. Orientalist painters found alibis for their homoeroticism in the high-handed scrutiny of “effeminate,” and thus backward, societies. “Slaves,” for instance, by the Spanish painter Gabriel Morcillo, a favorite artist of Francisco Franco’s, depicts a trio of young white men wearing turbans, chains, flowers, and little else. (They are, presumably, Christians, in thrall to a lascivious Moor.) A selection of propaganda images condemning male pederasty in the Islamic world—as horny as they are jingoistic—reminded me of the former Navy SEAL Robert J. O’Neill, who allegedly killed Osama bin Laden. O’Neill went viral on X, last year, for replying to a group selfie posted by young Kamala Harris volunteers with this: “You’re not men. You’re boys. If there was no social media, you would be my concubines.”

Some non-Western cultures responded to the new sexual regime with self-repression. Japan’s Meiji-era government proscribed homosexuality so as to be taken seriously as an empire. Similar backlashes took place in China, South Asia, Africa, and Eastern Europe. (Some of these regions are absent from the exhibition, because contemporary homophobia impeded loans.) Yet the modernist embrace of “primitivism” could also provide cover for homosexual expression, especially in settler-colonial societies with mixed roots. “Our Ancient Gods” (1916), by the Mexican painter Saturnino Herrán, depicts a group of flamboyantly posed pre-Columbian deities in loincloths and feather headdresses. Around the same time, Black American artists were leveraging a racialized reputation for hypersexuality into the riotous queerness of the Harlem Renaissance, expressed, for instance, in Richmond Barthé’s sinuously swaying sculpture “Feral Benga, Senegalese dancer” (1935), or the singer Ma Rainey’s “Prove It On Me Blues” (1928), written after her arrest for organizing a lesbian orgy. Despite the title, she makes no claim of innocence: “It’s true, I wear a collar and a tie,” Rainey sings, boasting that she can womanize “just like any old man.”

In the early days, homosexuality was considered a form of “gender inversion.” Its ideal object, for many artists, was the androgynous youth, whose incomplete sexual development was seen as analogous to the invert’s blend of masculine and feminine traits. Naked ephebes gambolled through the works of painters such as Gustave Courtois, whose “Narcissus” (1872), a rosy-cheeked boy with a daisy tucked into his headband seems to have fainted at the sight of his own reflection in a stream. Then, as the century turned, the boys were pushed aside by rough young men. Across the room, but painted thirty-five years later, is the same artist’s portrait of the bodybuilder Maurice Dériaz. Homosexuals were embracing the binary, Katz argues, and moving closer to our contemporary separation of gender from sexuality.

“Interior with Hendrik Christian Andersen and John Briggs Potter in Florence,” by Andreas Andersen (1894).Museo Hendrik Christian Andersen / Courtesy Wrightwood 659

The shift helped make transness and gender fluidity visible on their own terms. The show’s last section features works by photographers including Claude Cahun and Van Leo, who embodied a range of masculine, feminine, and neuter personae in their playful self-portraits. The Danish artist Gerda Wegener’s adoring paintings of her partner Lili Elbe were, in part, a collaborative fantasy about what Elbe might look like after her medical transition, which Elbe also discusses in “The Mystery of Gender” (1933), an interwar Austrian film. Yet, even as some crossed the binary, others dreamed of its abolition. Elisàr von Kupffer, a German-Estonian painter and aristocrat, considered gender divisions to be a perversion of god’s will. Christening himself Elisarion, he built a “temple” in Switzerland to propagate his doctrine, filling it with kitschy, “Midsommar”-esque idylls set in a so-called “clear world” of genderless Aryan youths. Von Kupffer was also a fascist, who wrote letters to Hitler. The Führer never replied.

Today, for better and worse, we’re living in Elisarion’s world. Young people are less and less inclined to define themselves in dichotomous terms, with “queer,” “bisexual,” and “nonbinary” gaining on the old labels. Fascism, too, is on the rise, and some have chosen to blame one for the other. The writer Andrew Sullivan recently opined that queer and trans radicals have hijacked a once respectable movement for gay and lesbian equality. The usual retort to such cavilling is to say that a trans woman threw the first brick at Stonewall. Arguably, though, Sullivan’s allegation of coattail-riding has it even more backward: if so many of the first homosexuals defined themselves as having a “soul” of the opposite sex, wasn’t it because, at the time, that was the more legible bid for acceptance than the bare fact of same-sex desire? (La Chevalière d’Éon was celebrated for living on both sides of the gender binary in a France where “sodomy” was punishable by death.) “The First Homosexuals” reminds us that, while labels may come and go, the need for solidarity remains. On the way out, I passed Beauford Delaney’s portrait, executed in a rainbow of pastels, of a young James Baldwin, who once wrote, “We must fight for your life as though it were our own—which it is.” ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com