Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

At one point in “Sorry, Baby,” a new film written and directed by, and starring, the actor and comedian Eva Victor, the main character, an English professor named Agnes, has an anxiety attack while driving. She pulls over into the parking lot of a roadside sandwich shop and comes upon the shop’s proprietor, a warm and gruffly paternal older man. “Something pretty bad” happened to her three years ago, she tells him. Although she doesn’t elaborate, the viewer knows that a trusted professor raped her when she was still in graduate school. She has since finished her program, and her best friend and primary emotional support, Lydie, has moved to New York, prompting Agnes to fear that she herself is frozen in place. When she encounters the kindly shop owner, it’s as if he has been conjured by the precise shape of her need. He responds to Agnes’s confession by putting together a sandwich, which she eats as she recomposes herself. Three years is “not that much time,” he says. “It’s a lot of time but it’s not that much time.”

“The whole thesis of the film” is in that line, Victor told me when we met in Los Angeles this spring. “Sorry, Baby” proposes a set of ideas about the mutability of trauma: that recovery is nonlinear, that the self is fluid, that time modulates the meaning of events, that life unfolds in a mix of genres. The shop owner’s words encapsulate a belief that strangers can “see you in a way that other people can’t,” Victor said. He’s one of several indications that “Sorry, Baby” takes place in a world that might be slightly magical, or at least softly impressionable to Agnes’s inner life.

As an homage to the sandwich scene, Victor and I were at a sandwich shop in the Silver Lake neighborhood. She was there when I arrived, standing to the side of the glass storefront. The café had an Instagram-ready vibe—mosaic tiles, olde-shoppe-style fonts, accents of bubblegum pink and robin’s-egg blue—but Victor was dressed as if to avoid notice, in black pants and a black sweatshirt. Her hair was drawn back in a messy bun. Waiting for our table, we sat and chatted on two of the child-size fluorescent stools outside. Time passed, and it became harder to ignore that the restaurant appeared to have forgotten about us. Presently, swapping her reticence for a politely commanding air, Victor unfolded herself from the tiny stool and approached the hostess stand. There followed a small commotion of friendliness—apologies, laughter—after which we were led to our seats and sent a free passion-fruit donut.

“Sorry, Baby,” which came out in New York and Los Angeles on June 27th, is stamped by Victor’s versatility. She started writing the intimate and meticulous film in earnest during the pandemic, when COVID halted the production schedule for “Billions,” the show on which she’d been playing a “genius quant” named Rian. Victor had been craving “private writing time and some reflection,” she said. She sublet her cousin’s house in rural Maine and began a contemplative, almost monastic interlude: lots of walking in the snow and the cold, lots of driving. She watched many movies and warmed many cans of split-pea soup.

When the writing was done, in 2021, Victor sent her script to Pastel, a production company headed by the director Barry Jenkins, who had cold-D.M.’d her a few months earlier, soliciting work. Victor knew she wanted to act in the feature; Jenkins suggested that she direct it, too. Pastel set up a two-day practice shoot to get Victor more comfortable behind the camera. She also shadowed her friend Jane Schoenbrun during the making of Schoenbrun’s movie “I Saw the TV Glow.” By 2024, Victor felt ready to film. She was moved by the number of people—strangers, initially—who supported her vision. “When you’re writing about someone feeling so isolated and so lonely, when the making of it becomes collaborative, that’s a special thing,” she told me. “To feel so seen and so heard” was a “profound transformation.”

The film is animated by a remarkable tenderness toward Agnes and toward survivors of sexual violence in general. With one exception, characters avoid clinical or precise description of the incident, speaking instead of “the thing,” “the bad thing,” “something really bad.” Victor glossed these euphemisms as protective. “Sorry, Baby” “tries to take care of someone watching and to have a good bedside manner,” she said. But the movie’s linguistic delicacy also evinces intimacy with trauma’s subtler effects—its inexpressibility, its senselessness. Attempting to narrate her rape to Lydie, Agnes isn’t sure which details to prioritize, or what order to put them in, and her disjointed account captures her internal confusion. “I just got up,” she says at one point, “and I grabbed my boots, and I drove home, and now I’m here.”

In “Sorry, Baby,” Agnes has a vexed relationship with time, and Victor wanted to manipulate its flow to serve the character. The movie presents the years of Agnes’s life out of order, a choice that invites us into her experience of surreal circling rather than forward movement. Victor hoped that the structure of the film, which begins in the present and doubles back, would allow viewers to form an impression of Agnes independent of the assault: “I wanted to give her a fighting chance at being complicated and interesting.” The first part of the movie “is all about these two people”—Agnes and Lydie—“and their love for each other and their joy in their friendship.” Early scenes are defined by the easy charisma of the performers and organized around the news that Lydie is pregnant. As the film proceeds, we encounter details (Victor referred to them as “little ghosts”) that seem ordinary or neutral. In one scene, Agnes is wearing a pair of chunky combat boots, and old, worn pages of her thesis are taped to her window. Later, we learn that she was wearing the same boots when she was raped; she covered her window afterward so that no one could look inside.

Narratives of female pain often traffic in the mystique of the wounded woman: we see characters from without and are seduced by their reticence, their secrets. But Victor is interested, nearly exclusively, in what such damage feels like internally. There’s something quietly radical about the way “Sorry, Baby” privileges Agnes’s subjectivity while also exploring her trauma. A detail like the pair of combat boots only becomes unsettling as we move deeper into Agnes’s perspective. Consequently, we neither leer at Agnes nor romanticize her; we aren’t waiting for a horrific revelation to resolve her enigmas and snap her into place.

This refusal to sensationalize marks a departure from many books and movies with trauma plots. As the critic Parul Sehgal has argued, such fare frequently bestows dark backstories on a protagonist in order to make her personality comprehensible. Until her past spills out, reframing her character traits as symptoms, the archetypal weeping woman remains “opaque,” Sehgal writes. But Agnes is less a creature of rarified glamour than a person struggling in ordinary ways with loneliness and disquiet. Her life, we sense, will always seem more fraught and mysterious to her than it seems to us, because it is her confidence that has been undermined, her sense of normalcy disrupted.

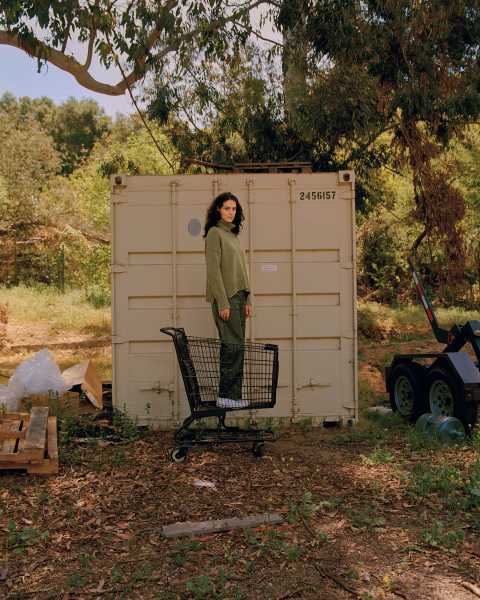

Victor communicates Agnes’s alienation by playing her as visibly self-conscious. She strikes stylized poses and projects a defensive theatricality; for all its naturalism, the movie itself has a mannered quality. Because many of the scenes are shot through windows or doorways, the camera can seem sympathetic to Agnes’s struggle to regain control. It’s as if the film is reflecting the character’s wish to construct careful tableaux of her own life. There’s a corresponding feeling in “Sorry, Baby” of imprisonment, maybe self-imposed. Victor said, “The image of the film in my head is Agnes looking out this closed window and trying to decide if she wants to go outside or hide inside forever.”

Victor emphasized that the structure of “Sorry, Baby” is meant to “support the film being about friendship, love, and care.” The film “decenters violence” by skimming over the event itself in favor of “one friend telling the other friend what happened and the friend holding it very well.” The assault scene is shot with particular circumspection. Agnes has gone to see her thesis adviser, Professor Decker (Louis Cancelmi), at his house. Although they’re indoors, we are shown only the outside of the building, impassive in the changing light. When she emerges, the camera stays close to the back of her head as she walks to her car, and her face remains obscured and shadowy until she gets home. Lydie is there, and she questions Agnes, at which point the camera reveals Agnes, in closeup, for the first time. “That’s a real journey of trying to give the audience the same experience as Agnes, trying to make sense of what happened, but not being seen until Lydie sees her,” Victor said. “The reason we’re given full access is because Lydie is there and is a witness, and Agnes is safe, finally.”

“Sorry, Baby” unspools in an idyllic college town, with painted clapboard buildings and a romantic lighthouse and pine trees whose fragrance you can almost smell. The film explores the promise of higher education—that it will sculpt young people into the adults they are supposed to become—and the unique disillusionments that can result when that promise is betrayed. One scene shows Agnes in professor mode, effortlessly holding the attention of her class during a discussion of “Lolita.” As the light filters through the windows, the students laugh and ask questions; there’s a creative flow in the room. Agnes, draped in autumnal tweed and khaki, elevates her seminar into a kind of allegorical stage for academia. We are seeing someone’s dream of what education might be, at its best—an art. “The scene where she’s a professor was really important to me, because it’s actually the scene where she’s doing the thing she loves,” Victor said. “There’s hopefully a lack of self-consciousness in that moment, when she’s alive, and this is her joy.”

Earlier in the film, in a flashback, Professor Decker tells Agnes that she is “extraordinary” and texts her photos of his appreciative underlinings in her papers. He is every inch the supportive mentor, the pair of hands holding the divining rod that leaps at her potential—until he takes advantage of her, stripping her of what Victor described as “creative energy and trust in herself.” Decker’s character could be read as a kind of negative tribute to the formative educators who built up Victor’s own confidence. For ten years, she said, dipping a corner of her grilled cheese into a bowl of tomato soup, she sang in a “very intense, very disciplined” chorus. (The group may not have wholly disciplined the desires it fostered, she added. “There was a lot of unspoken queerness, especially in the Alto II section.”) She reminisced about a high-school theatre teacher who “saw how much the work mattered to me” and “took me seriously.” At Northwestern University, where she went to college, her acting and playwriting professors “treated me like a professional when I was still growing up.”

After graduating, Victor moved to New York City. “I worked at the front desk of every gym in the world,” she told me. She also nannied (“Probably more like babysitting”) and helped with fittings at a bridal shop (“You witness some real gender euphoria and dysphoria”). In 2017, she landed a part-time writing gig at Reductress, an online feminist humor magazine, where she churned out as many as four posts a day, with headlines including “This Puppy Knows Exaaaaaaactly What It’s Doing” and “Get It, Bitch! This Woman Got in the Shower.” As an actor, Victor was used to channelling personae, but Reductress taught her how to write in a voice that wasn’t hers—brassy, informed, sardonic. The experience made her curious about what jokes she might craft in her own voice.

In 2019, Victor started posting short videos on Twitter in which she inhabited ridiculous characters, such as a glamorous wife who “def did not murder my husband” and a girl encouraging her boyfriend to celebrate Straight Pride. One sketch, titled “the girl from the movie who doesn’t believe in love,” is a spritely parody of romantic-comedy tropes, from the female lead’s asocial snark (Victor’s version: “I like eating things out of jars, and going to bed at 10 P.M., and having a bush”) to the weepily autobiographical toast at someone else’s wedding.

In retrospect, part of the videos’ appeal may have been Victor’s hyper-alertness to femme stereotypes. A finespun kind of drag, they mocked some of the same things that Reductress did, but with a lighter touch, and they regularly went viral, racking up millions of views. Victor’s characters were magnetically awkward, their address was intimate and direct, and their creator scanned as a pretty weirdo with a tap on the discourse and on the possibilities of the contemporary internet. “There are a few I’m proud of,” Victor told me, of the videos. “But I’m more proud of them because I’m proud of the person who made them,” who was “trying something” and getting over “the humiliation of being seen.”

Victor funnelled her offbeat comedic sensibility into “Sorry, Baby.” The film is often very funny. Characters seem to utter words in the exact order in which they think them, and their phrasing has a zany, untutored elegance—an artful artlessness that reminded me a bit of the dialogue in a Sally Rooney novel. Agnes’s affect, which can be blunt, hyper-literal, and emotionally flat, draws on a spectrum-y aesthetic that’s popular online. “Why am I still working on this,” Lydie wails, referring to her thesis. “Because you didn’t finish it,” Agnes deadpans. “No offense.” The film’s humor is slippery: beguiling but also uncomfortable—Victor referred to it as a “tonal tightrope.” She wanted both Agnes and the audience to have some relief, but she also wanted to honor the intensity of the movie’s subject matter. She spent a lot of time monitoring the ratio of jokes to drama, she told me. Often, she said, she would be tempted to put in a laugh-out-loud moment, but she’d end up scaling the humor back. “I had to keep reminding myself, ‘Just say the line and let it be true,’ ” she recalled. Comedy in the film sometimes feels like a strategy for evoking life’s unpredictability. When Agnes is called to jury duty, she hesitates to tell the prosecutor that she has been the victim of a crime, asking whether she could “get in trouble” for giving too much detail. “Why would you get in trouble?” the prosecutor asks, the bafflement in her voice underlining the terrible sadness of the question. “I don’t know, the law makes no sense in my opinion,” Agnes mutters, and comedy steals around a blind corner to surprise us.

The film’s oscillation between comedy and drama speaks to Victor’s comfort with letting her work be more than one thing. “Sorry, Baby” makes flux a theme as well as a formal characteristic. Toward the end of our conversation, Victor touched on a recent decision to start moving in and out of pronouns. She likes to use “she” and “they” interchangeably, in recognition of “how limitless one person can be, and how much shifting can happen day to day, moment to moment.” The existing “boxes,” Victor said, were starting to feel “stuffy” and uncomfortable.

Victor wrote some of this into the film. About two years after the assault, Agnes must identify her gender on a government form. After a moment of staring at the paper, she draws and fills in her own box between “M” and “F.” Victor glossed the moment as the result of an epiphany—Agnes realizes that the rules she has lived by are neither binding nor fair. “There’s a leaving of the body that happens after a trauma like this,” Victor told me. “For Agnes, at least, I think there’s an understanding that maybe there are things about her experience in this body and in this world that she was given without a choice.” Agnes is looking at her options, Victor said, and she doesn’t like them. “It’s her little rebellious moment of ‘this form doesn’t work for me.’ ”

If the trauma plot can have a one-size-fits-all quality, “Sorry, Baby” considers, with rigor and sensitivity, trauma’s effect on a specific person—a nonconformist, someone who feels slightly out of true with the world. A subtly tragic consequence of Agnes’s assault is that her decisions, especially those that run counter to societal norms, begin to be shadowed by what happened to her. Even before the rape, Agnes held herself apart. Afterward, her faint aura of isolation or separateness might be read as a symptom. Is Agnes choosing her actions freely or merely following the dictates of her pain?

This dynamic comes through most strongly near the end of the movie, when Agnes takes a bath with Gavin (Lucas Hedges), a sweet and solicitous neighbor whom she’s started to casually date. He asks her whether she wants “the stuff that everyone has”: marriage, kids. She says she’s not sure. “The thing that she’s been deprived of is the ability to discern what she wants and what she’s capable of,” Victor told me.

Agnes isn’t “able to dream” at this point, Victor continued. “She’s just day-to-day functioning.” In the wake of trauma, a veil of doubt has dropped over Agnes’s motivations, and she has become a stranger to herself. She can’t determine whether her failure to rack up bourgeois milestones à la Lydie reflects her ruination or simply her alternative desires. On one hand, not wanting kids could signal that Agnes is as stalled and isolated from the human world as she fears she is. Yet if Agnes does decide to have children, she’ll be haunted by the worry that she is simply trying to disprove a sexist cliché. (As Victor put it, “there’s something male-gaze-y and flip about the trope that someone who survived this kind of thing would not want to be a mom.”) The lingering cruelty of an act like Decker’s is that, regardless of how Agnes arranges her future, she will wonder whether she has let his violation push her off course.

It is risky, particularly for a début film, to attend so minutely to the wounds of a protagonist, to wait anxiously on her perceptions and emotions. What saves the movie from sentimentality is the weight the viewer feels bearing down on Victor’s snow-globe universe. The exquisitely careful handling of the central character, the euphemistic dialogue, the visual omissions—they all stand on one side of the ledger. On the other side is the destabilizing fear that the world has reached down to punish Agnes for inclining toward an unorthodox life.

After lunch, Victor and I wandered down the street to a nearby park. The day was cool and pleasant and mostly overcast, but periodically the sun swept it golden. We sat at a picnic table and watched a group of children chase bubbles. The differently sized bubbles blew around our table, their fragile skins shining. Victor speared one on her fingertip, popping it. “Why did I do that?” she exclaimed in dismay. Turning philosophical, she asked, “What is this childlike desire to hold something unholdable?”

The kids shouted in the background. I thought of the carillons that ring occasionally on “Sorry, Baby” ’s campus, diffusing an atmospheric beauty that almost obscures their purpose—to mark time. In the film, the bells keep track of what Agnes has internalized as her failure to heal. She feels as though Lydie and the rest of the world are moving forward while she’s stuck in the past. But the bells also register Agnes’s distance from the assault; they carry her further away from it. No one, including Agnes, knows how her life will turn out. Three years is a lot of time but it’s not that much time.

A few bubbles floated past. Victor let them go.

She offered, “I think that Agnes is probably someone who doesn’t want the stuff that everyone has.”

What about Victor? “I don’t even know what conventional means anymore,” she said. “I want a life full of love and connection. I feel pretty happy operating day by day right now. That’s my unconventional perfect life right now.” ♦

An earlier version of this article misidentified the wide-release date of “Sorry, Baby.”

Sourse: newyorker.com