Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

“The New Art: American Photography, 1839–1910,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 20th, is a big, sprawling show of work from the medium’s era of busy development, as one format improved on and eclipsed another, and photography became a popular art. The show’s charting of the technical and scientific refinements that led from unique daguerreotypes to reproducible cartes de visite and stereographs help ground what could have been a dry and academic exhibition in a sense of discovery. The photographers, including a slew of amateurs and “unknown makers,” were literally taking the medium into their own hands and exploring the possibilities of a new form of expression, a new way of seeing.

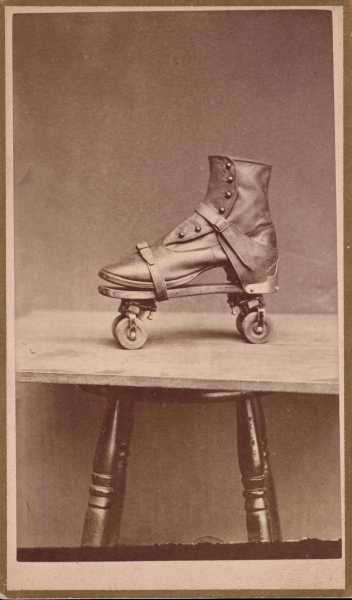

Roller Skate and Boot. Albumen silver print from glass negative, 1860s.

By focussing on work made in America, “The New Art” also charts a country and a democracy defining itself bit by bit. Because a daguerreotype was the unique result of a painstaking and expensive process—wall text describes an “image formed on the surface of a silver-plated sheet of copper fumed with iodine” and “developed with hot mercury vapors”—its use was usually reserved for studio portraiture. Posed before a painted backdrop, with drapery and props that suggest a stuffy funeral parlor, lawyers, businessmen, and society matrons, dressed as if for a wedding reception, remained absolutely still for as long as it took to fix an image, typically twenty to forty seconds at the time most of these examples were made. Each finished plate, as reflective as a mirror, was presented in a brass mat, often hinged to a silk or velvet-lined panel that closed to form a book-like case, not unlike a cosmetic compact. The Met’s selection—from a private collection amassed by the American photography dealer William L. Schaeffer, and now a “promised gift” to the Met—nods to the format’s association with establishment wealth and power while showcasing a decidedly democratic range of subjects: a farmer with his tools, a blacksmith behind his anvil, a dapper young man with a rooster, and two children in postmortem portraits, laid out for formal viewing.

Woman Wearing a Tignon. Daguerreotype with applied color, circa 1850.

In the beginning, photography was largely a specialists’ medium, the domain of a few inventors and commercial studios. Although the daguerreotype required a high level of expertise, the process made the medium accessible to a wider range of enthusiasts. The works on view at the Met have a remarkable depth and presence, and their handsome presentation emphasizes their appeal as keepsakes. Not everyone could make a daguerreotype, but nearly everyone could own one. By the turn of the century, photography had found a proud, comfortable place in the American home.

Schoolmaster Hill Tobogganing, Franklin Park, Roxbury, Massachusetts. Cyanotype. 1905.

Winter on the Common, Boston. Salted paper print from glass negative, 1850s.Photograph by Josiah Johnson Hawes

The earliest photography was voracious and encyclopedic. There was a whole world of things that had never been seen in this particular, startlingly realistic way. People were especially intrigued by imperial, foreign, and exotic subjects: queens, presidents, and maharajahs; Gothic cathedrals, volcanic mountains, the pyramids, a herd of elephants, a rickshaw. But, as the medium became more accessible, it also became more personal. People wanted to see themselves and people like them. Photographs became not just documents but mementos, and the memories they preserved were treasured and passed on. Photographers also took note of the entirely ordinary and ephemeral things around them: a shelf of glassware, a broom in a courtyard, a tree, a leaf. This is especially evident as the show builds from format to format—including tintypes, ambrotypes, paper prints, and stereographs, each an improvement on the last where the maker’s control was concerned. Although a number of images are credited to known studios or established photographers like Alice Austen, Carleton Watkins, Mathew Brady, and Eadweard Muybridge, there are no trophies here, and much of the modern work is by little-known or unknown makers. The best curators are not just connoisseurs or experts in their fields; they have something undefinable, something that “taste” doesn’t really cover—an understanding, sympathetic, and discerning eye that sees beyond the surface to something emotional and hard to pin down. “The New Art,” curated by Jeff Rosenheim, the reliably sharp and witty head curator of the museum’s department of photographs, is full of pictures chosen for what they convey about their moment in history: Atlanta in ruins in 1866, the shattered façade of a building that barely survived the San Francisco earthquake, the scars of a formerly enslaved man in the famous image “The Scourged Back.”

Young Man Laying on Roof. Albumen silver print, 1880s–90s.Photograph by Chauncey L. Moore

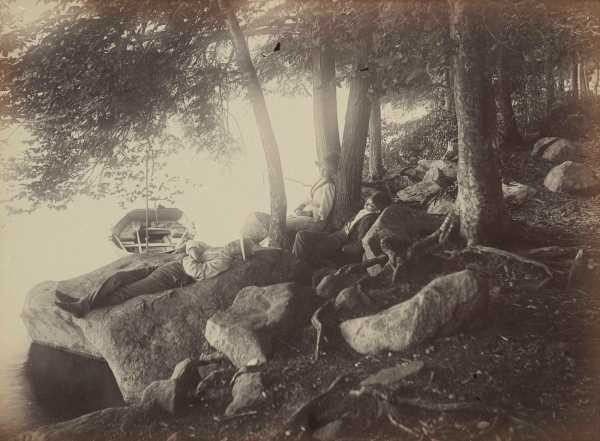

But the vernacular and ahistorical images are what give the show its rich, tangy flavor. One favorite is Austen’s dreamy image of a group of men and women lounging in the woods by a lake in the summer of 1888; dappled sunlight gives the image echoes of Monet. Many of the pictures have a surreal or a comic edge: a study of a woman’s leather boot strapped onto a roller skate; a stereo view of a stack of giant hailstones; an alarming portrait of Isaac W. Sprague, the “Living Skeleton.” One picture shows a child standing next to a display of astronomical instruments—a readymade that Yves Tanguy would have envied. All history should be this surprising and engaging, a leisurely guided tour expertly arranged and wide open to discovery.

Group on Petria, Lake Mahopac. Albumen silver print from glass negative. August 9, 1888.Photograph by Alice Austen

Sourse: newyorker.com